An extinct tree grows in India’s Kalakad-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve.

Well, it’s not exactly extinct. But the small, flowering tree species, known only as Wendlandia angustifolia, has had a long history of going unnoticed.

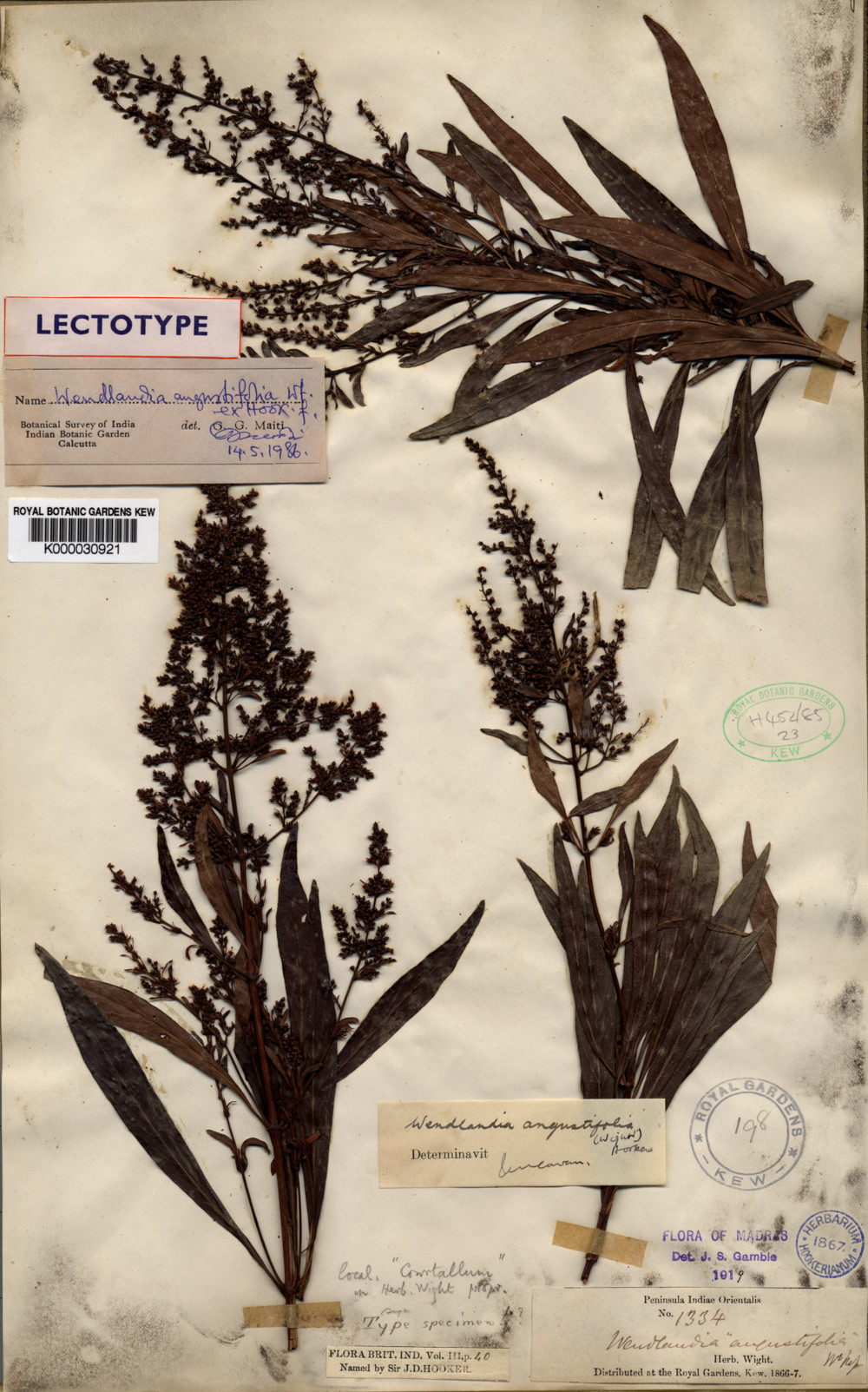

Scientists collected the first specimen of the plant in 1867, then didn’t observe it again until 1917. After that no one officially saw it for another 81 years — possibly because the initial descriptions had placed it in the wrong location. But the observation in 1998 wasn’t published in the scientific literature until 2000 — two years after other scientists declared the long-unseen species to be extinct. It’s been listed that way on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species ever since.

In part that error has persisted for 22 years because rare plants don’t get much conservation attention or funding compared to charismatic megafauna like the reserve’s titular tigers. And because of that, no one took the effort to assess the potential conservation needs of the rediscovered species.

Meanwhile occasional sightings of the plant continued, including a fortuitous specimen collection in 2011 by Ladan Rasingam of the Botanical Survey of India. But the species’ categorization remained unchanged.

Recently, though, researcher Chellam Muthumperumal proposed a project to assess rare plants in Western Ghats. In response Rasingam suggested he look for Wendlandia angustifolia and finally determine its conservation status.

And now, 138 years after the species was first described, we finally know how many Wendlandia angustifoliaI exist in the world, how they’re doing, and whether they’re in need of protection.

The results, published recently in the Journal of Threatened Taxa, suggest we should have gone looking a lot earlier.

Muthumperumal and his colleagues found just 1,091 individual trees growing along seven gently flowing, rocky streams in the tiger reserve. That may seem like a decent number, but the majority — 862 trees — were seedlings and saplings, each under three feet high with trunks less than four inches in circumference. Only 54 trees were large enough to be considered “established individuals.”

While a few of those mature trees reached about 20 feet in height, most exhibited stunted growth. Some weren’t much taller than the saplings — likely a side effect of the region’s seasonal floods and droughts.

Despite their “dwarf” status, the mature trees seemed healthy.

“They are mature enough to produce flowers and fruits even in the dwarf condition,” Muthumperumal says. That probably explains why there were so many young trees nearby. But the floods and drought may prevent many of those young trees from growing up enough to also reproduce and help keep the species going. Disturbance by tourists visiting the reserve could also play a role, he notes.

As a result of the small population, low level of mature trees, and the continued threat from flooding and drought, Muthumperumal — who now hopes to assess more of India’s rare plants — says he and his colleagues are preparing a note to the IUCN to finally change the species’ status from “extinct” to “endangered.”

That, in turn, could inspire new conservation efforts to preserve this rarely seen tree. The paper mentions the importance of additional searches to see if the tree exists in other parts of the reserve, regular monitoring, and “an immense need to implement a restoration program to conserve this narrow endemic tree species.”

We hope that won’t take another 22 years.

![]()