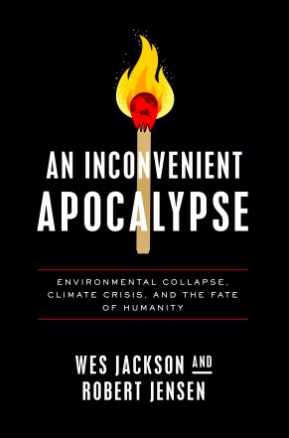

This essay is adapted from An Inconvenient Apocalypse: Environmental Collapse, Climate Crisis and the Fate of Humanity.

Allow us to be blunt about the current state affairs within the human family and in the larger living world: Things are bad, getting worse, and getting worse faster than we expected.

The human species faces multiple cascading social and ecological crises that will not be solved by virtuous individuals making moral judgments of others’ failures or by frugal people exhorting the profligate to lessen their consumption. This is happening not just because of a few bad people or bad systems, though there are plenty of people doing bad things in bad systems that reward people for doing those bad things. At the core of the problem is our human-carbon nature, the scramble for energy-rich carbon that defines life. Saying “no” to dense energy is hard.

Technological innovations can help us cope but cannot indefinitely forestall the dramatic changes that will test our ability to hold onto our humanity in the face of dislocation and deprivation. Although the worst effects of the crises are being experienced today in developing societies, more affluent societies aren’t exempt indefinitely. Ironically, in those more developed societies with greater dependency on high energy and high technology, the eventual crash might be the most unpredictable and disruptive. Affluent people tend to know the least about how to get by on less.

When presenting an analysis like this, we get two common responses from friends and allies who share our progressive politics and ecological concerns. The first is the claim that fear appeals don’t work. The second is to agree with the assessment but advise against saying such things in public because people can’t handle it.

On fear appeals: The reference is to public education campaigns that seek, for example, to reduce drunk driving by scaring people about the potentially fatal consequences. Well, sometimes fear appeals work and sometimes they don’t, but that isn’t relevant to our point. We are not focused on a single behavior, such as using tobacco, nor are we trying to develop a campaign to scare people into a specific behavior, such as quitting smoking. We are not trying to scare people at all. We are not proposing a strategy using the tricks of advertising and marketing, the polite terms in our society for propaganda. We are simply reporting the conclusions we have reached through our reading of the research and personal experience. We do not expect that a majority of people will agree with us today, but we see no alternative to speaking honestly. It is because others have spoken honestly to us over the years that we have been able to continue on this path. Friends and allies have treated us as rational adults capable of evaluating evidence and reaching conclusions, however tentative, and we believe we all owe each other that kind of respect.

We are not creating fear but simply acknowledging a fear that a growing number of people already feel, a fear that is based on an honest assessment of material realities and people’s behavior within existing social systems. Why would it be good strategy to help people bury legitimate fears that are based on rational evaluation of evidence? An obsession with so-called positive thinking not only undermines critical thinking but also produces anxiety of its own. Fear is counterproductive if it leads to paralysis but productive if it leads to inquiry and appropriate action to deal with a threat. Productive action is much more likely if we can imagine the possibility of a collective effort, and collective effort is impossible if we are left alone in our fear. The problem isn’t fear but the failure to face our fear together.

On handling it: It’s easy for people — ourselves included — to project our own fears onto others, to cover up our own inability to face difficult realities by suggesting the deficiency is in others. Both of us have given lectures or presented this perspective to friends and been told something like, “I agree with your assessment, but you shouldn’t say it publicly because people can’t handle it.” It’s never entirely clear who is in the category of “people.” Who are these people who are either cognitively or emotionally incapable of engaging these issues? These allegedly deficient folks are sometimes called “the masses,” implying a category of people not as smart as the people who are labeling them as such. We assume that whenever someone asserts that people can’t handle it, the person speaking really is confessing, “I can’t handle it.” Rather than confront their own limitations, many find it easier to displace their fears onto others.

We may not be able to handle the social and ecological problems that humans have created, if by “handle” we mean considering only those so-called solutions that allow us to imagine that we can continue the high-energy/high-technology living to which affluent people have become accustomed and to which others aspire. But we have no choice but to handle reality, since we can’t wish it away. We increase our chances of handling it sensibly if we face reality together.

In a culture that encourages, even demands, optimism no matter what the facts, it is important to consider plausible alternative endings. Anything that blocks us from looking honestly at reality, no matter how harsh the reality, must be rejected. To borrow an often-quoted line of James Baldwin, “Not everything that is faced can be changed; but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” The line is from an essay titled “As Much Truth as One Can Bear” about the struggles of artists to help a society, such as white supremacist America, face the depth of its pathology. Baldwin, writing with a focus on relationships between humans, suggested that a great writer attempts “to tell as much of the truth as one can bear, and then a little more.”

We would take Baldwin a step further. Many people can tell only those truths that the power system can bear to hear. Others will dare to tell as much of the truth as one can bear and then a little more. But in the face of multiple cascading crises, we have to tell as much of the truth as one can bear, then a little more, and then all the rest of the truth, whether one can bear it or not.

If it seems like all the rest of the truth is more than one can bear, that’s because it is. We are facing new, more expansive challenges than ever before in history. Never have potential catastrophes been so global. Never have social and ecological crises of this scale threatened at the same time. Never have we had so much information about the threats that we must come to terms with.

If that seems overwhelming, that’s because it is overwhelming. No one living at this moment in history — including the two of us — can really bear all of the truth. But we stand a better chance of fashioning a sensible path forward if we help each other bear all of that unbearable truth.

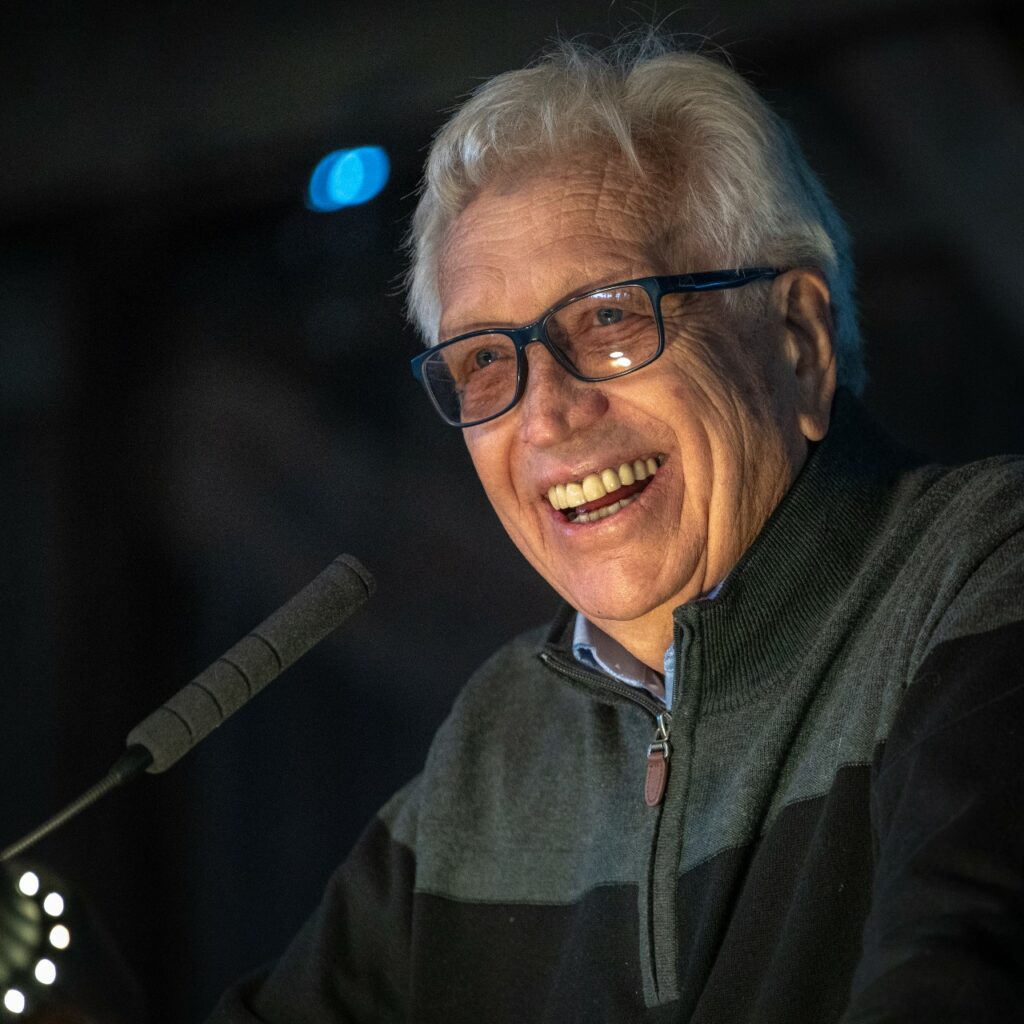

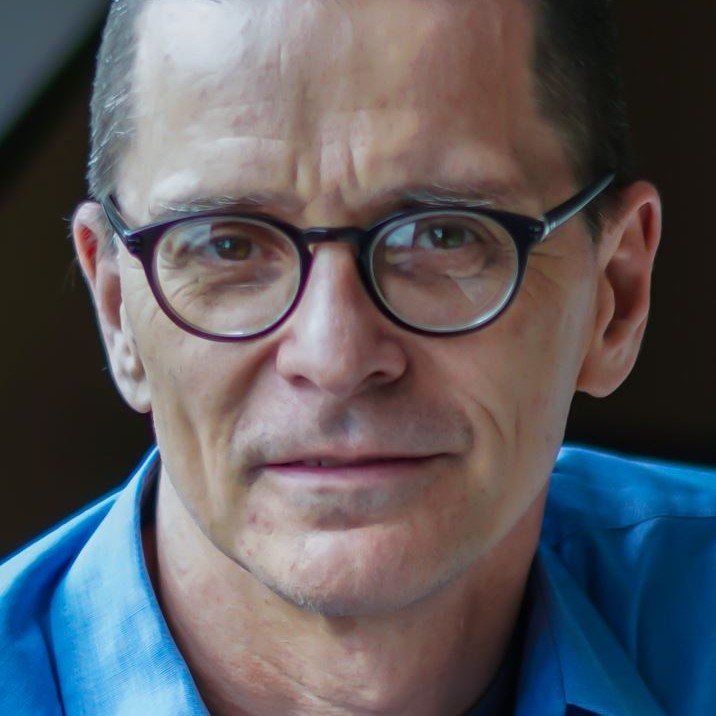

© Wes Jackson and Robert Jensen

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.

Get more from The Revelator. Subscribe to our newsletter, or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Previously in The Revelator:

How We Got Here: Ecological Restoration’s Surprising History