Is renewable energy always sustainable — or just? Today we launch a two-part series looking at the role of Canadian hydropower in helping the U.S. Northeast meet its climate goals.

Construction could start soon on New England’s biggest renewable energy project, a 1,200-megawatt-capacity transmission line to deliver renewable energy to Massachusetts customers. The proposed project, New England Clean Energy Connect, has cleared most of its significant regulatory hurdles. But it hasn’t been without opposition.

Some of the fiercest challenges have come from environmental groups, who question the purported green benefits. That’s because this isn’t a wind or solar project — it’s big hydro imported from Canada. The power would come from a massive network of 63 hydropower stations and numerous large dams owned by Hydro-Québec, a monopoly utility run by the province. Some of this energy could travel more than 800 miles from turbine to light switch.

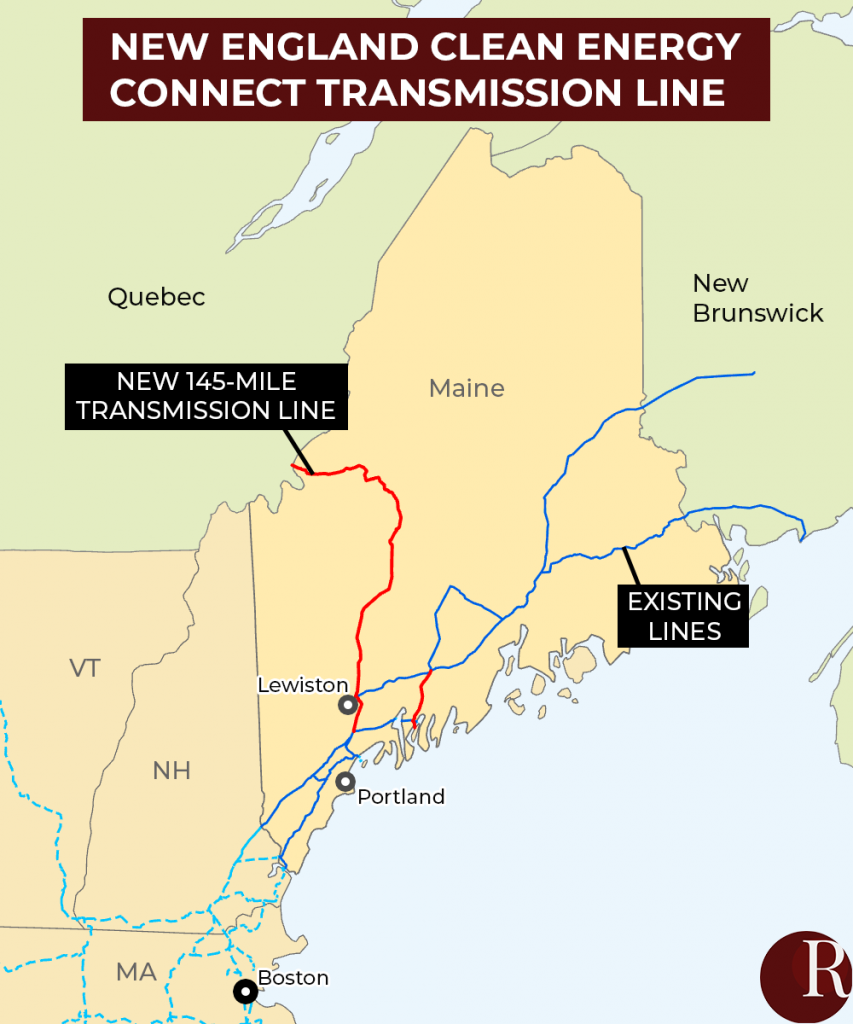

And in order to get the power to Massachusetts, 145 miles of new high-voltage direct current transmission line will need to run through Maine — including more than 50 miles slashed through the North Maine Woods.

The project is regionally significant but also nationally important. New England is getting serious about climate change, with all six states pledging to cut greenhouse gas emissions 80% over 1990 levels by 2050. Neighboring New York has even greater ambitions — and is similarly interested in importing Canadian hydropower.

Hydro-Québec already supplies about 17% of the electricity for New England and 5% for New York, and the company has been banking on those numbers increasing. “We’re poised to play a bigger role,” says Gary Sutherland, director of strategic affairs for northeast markets at Hydro-Québec.

NECEC would lock in a 20-year contract for Hydro-Québec and partner Central Maine Power to deliver about one-fifth of Massachusetts’s electric power needs to its utilities. But is the project worth hailing as a big step in fighting greenhouse gas emissions, or is it committing the region to decades of energy from a source that fails to live up to its environmental promise?

Project Selection

Project Selection

In order to up its clean energy game, Massachusetts passed legislation in 2016 requiring its electric utilities to secure about 9.45 terawatt-hours per year of low-carbon power by 2022. In a competitive bidding process to solicit projects, the state received 46 clean energy proposals, many wind and solar, but decided to go with hydropower — with a very long extension cord.

The winning selection at the time, a project called Northern Pass, was pitched as a 200-mile-long transmission line — much of which would be buried underground or follow existing corridors — to import Quebec hydroelectric power through New Hampshire’s White Mountains.

But New Hampshire regulators rejected the plan. The evaluation committee unanimously found that applicant Eversource Energy “failed to demonstrate by a preponderance of the evidence that the Project would not unduly interfere with the orderly development of the region,” which includes tourism, property values and existing rights of way. They also took issue with the project’s proposed benefits in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Eversource appealed the decision, but the state Supreme Court later upheld the committee’s ruling.

Massachusetts then moved a state east and selected a similar project, New England Clean Energy Connect, that would instead move the power through Maine in a transmission line constructed by Central Maine Power, a subsidiary of Avangrid, which is owned by the Spanish multinational utility Iberdrola.

Unlike the proposed Northern Pass project in New Hampshire, virtually all of the Maine project, which is estimated to cost Massachusetts ratepayers close to $1 billion, will be aboveground. This includes a 54-foot-wide corridor stretching 53 miles through the North Maine Woods, the largest contiguous temperate forest in North America. The transmission line would fragment forest and aquatic habitat across a region that’s home to American martens, ovenbirds, endangered wood turtles and threatened Canada lynx.

Despite the project costs, Bay State residents are expected to see electrical rates drop between 2-4% a year — a savings estimated at nearly $4 billion over the two-decade-long contract, according to the project partners, Central Maine Power and Hydro-Québec.

All the new infrastructure for the project will be built in Maine, but the primary beneficiary will be Massachusetts. Some recent concessions sweetened the deal for Maine residents, though, and helped bring around Maine Gov. Janet Mills and environmental groups like the Conservation Law Foundation (which was an outspoken opponent of Northern Pass) and the Acadia Center.

A small slice of discounted energy would go to Maine — enough to supply 70,000 homes or 10,000 businesses. But so far it’s unclear who the buyer for that power in Maine would be. The deal also accelerates the distribution of a fund for the state that includes $170 million in rate relief and clean energy projects, including heat pumps and electric vehicles.

The Natural Resources Council of Maine, however, wasn’t swayed by the new stipulations. The environmental nonprofit, which works on statewide conservation and climate issues, has fought the project at every turn.

Sticky Greenhouse Gas Emissions Issues

One of the biggest sources of contention with the project is how much it will actually reduce greenhouse gas emissions, which is, after all, the driving force behind bringing clean energy projects into the mix.

NECEC will reduce New England greenhouse gas emissions by 3 million tons a year by displacing dirtier fuels from the grid — the equivalent of taking 700,000 cars off the road.

“And that may be true, but it’s also irrelevant,” says Nick Bennett, staff scientist at the Natural Resources Council of Maine. “It doesn’t matter if you reduce greenhouse gas emissions in New England by 3 million tons if they just go up by a corresponding amount elsewhere.”

Because the project doesn’t involve the construction of new generating facilities, Bennett says he’s concerned that Hydro-Québec will simply shift power from existing customers in order to send it to Massachusetts, which is willing to pay more.

“We get this big power line pushed through Maine, Hydro-Québec and Central Maine Power get rich, but there are no global reductions in greenhouse gas emissions because other jurisdictions that get power from Hydro-Québec now are going to lose that power and they’re going to have to make up for it quickly,” he theorizes. “And that means natural gas or coal.”

Bennett and the Natural Resources Council of Maine aren’t the only ones who share this concern.

When New Hampshire regulators rejected the Northern Pass route, they came to a similar conclusion, finding in their decision that “no actual greenhouse gas emission reductions would be realized if no new source of hydropower is introduced and the power delivered by the Project to New England is simply diverted from Ontario or New York.”

In Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey’s office, which looks out for the state’s ratepayers, was also concerned the contract language left open the possibility that hydropower already being sold by Hydro-Québec would simply be moved to the new contracts for NECEC, and it wouldn’t necessarily amount to an addition of clean energy.

Representatives from Hydro-Québec, however, say they have been ramping up their operations for more than a decade in anticipation of exporting additional energy into the Northeast U.S.

“We have been developing our generation resources over the last 16-17 years because it takes a long time to actually bring a hydropower generating station online,” says Sutherland. “We went on a pretty extensive build-out phase in the early 2000s.” That, he says, should be enough to supply this new demand and existing customers, although the company is also hoping to secure new projects in other northeast states, as well, in coming years.

More Tricky Accounting

Hydro-Québec’s new capacity — an estimated 5,000 megawatts in recent years — is not without environmental cost, either. But determining the greenhouse gas footprint of hydropower isn’t straightforward.

Harnessing the power of rivers was once thought of as a zero-emissions energy source, but studies in the past decade have shown that’s not the case.

Reservoirs can emit methane and carbon dioxide — in some cases on par with fossil fuel power plants. But calculating those emissions isn’t as simple as measuring what’s spewing out of a coal stack.

That’s because a ton of variables affect what a reservoir emits, including the geographic location, climate, the area of land that’s flooded, the type of submerged vegetation, management practices, and the age of the impoundment. This last factor is especially important because many reservoirs emit more greenhouse gases in the first years (sometimes decades) after they’re filled, as submerged organic matter breaks down. Measuring emissions five years or 50 years after reservoirs become operational will lead to much different numbers.

Studies have also shown that emissions are particularly high in tropical regions where there is a lot of vegetation that decomposes in warm waters. But a 2019 study in Environmental Science and Technology found that the best indicator of greenhouse gas emissions is the “ratio of reservoir surface area to electricity generation.” A large, shallow area — characteristic of many reservoirs in Canada’s boreal forests — will release a lot more emissions relative to the power generated than damming a steep, rocky valley where more power is generated in a smaller space.

“Some of Hydro-Québec’s reservoirs flood thousands of square kilometers of forest land and they’re not all that deep,” says Brad Hager, a professor of earth sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and co-director of one of MIT’s Low Carbon Energy Centers. “So they emit a lot of carbon dioxide, but they don’t generate as much electricity per amount of water in the dam.”

In testimony to the Army Corps of Engineers, Hager, who’s also a part-time Maine resident, said that Hydro-Quebec’s operations are “definitively not the source of green power that they are made out to be.”

Research on the global carbon footprint of hydropower showed that six of Hydro-Québec’s reservoirs rank in the top quarter of the world’s biggest emitting hydro facilities.

A 2012 study published in the journal Global Biogeochemical Cycles looked at emissions from Hydro-Québec’s Eastmain‐1 reservoir, which flooded a boreal forest in Northwest Quebec in 2006. The reservoir, constructed during the time the company was ramping up to meet export goals, stretches across nearly 380 square miles with an average depth of 36 feet.

It’s only one of numerous dams run by the company, and emissions are likely to vary by project. Still, the results are illuminating.

The researchers, including one from Hydro-Québec, found that during the reservoir’s first year of operation it emitted 77% more carbon than a natural gas plant. And it took five years for it to reach the same level as natural gas.

They estimated that after 25 years, the reservoir’s emissions would be about 50% lower than gas and over a 100-year lifespan it will “emit the equivalent of 40% of the carbon emissions that the currently most efficient thermal power plant would have for an equivalent amount of energy production.”

In the long term, it’s an improvement over fossil fuels — but is that good enough, considering the timeline of the climate crisis we currently face?

Hager doesn’t think so.

“From my analysis of the average greenhouse gas footprint of Hydro-Québec, the electricity is not all that clean,” he says. “It’s probably on average a factor of two better than natural gas, but it’s like a factor of 20 higher than wind.”

That means that a contract to lock in hydro for two decades in Massachusetts could push out cleaner sources of energy at a time when they’re desperately needed to combat rising global greenhouse gas emissions.

“My main concern is that the long length of the contract with Central Maine Power and Hydro-Québec will put the dampers on renewables like solar and wind,” he says.

That could be a problem in Maine, too, in terms of transmission space.

Bennett says limited grid connections in Maine mean that NECEC “will make it very difficult for any other renewable energy projects to export their electricity.”

Other Environmental Problems

Beyond just the greenhouse gas issues are the obvious environmental harms that come from damming and diverting rivers and razing carbon-sequestering forests in the process. This includes damage to fisheries, loss of sediment and natural river flows, and the accumulation of methyl mercury in the aquatic food web — a human health risk, especially for Indigenous communities that rely on subsistence resources.

“As we all know dams irreversibly destroy rivers,” says Meg Sheehan, coordinator of the nonprofit coalition North American Megadam Resistance Alliance, which has been fighting the construction of big dams in Canada and the exportation of energy to the United States. “Hydro-Québec’s dams are so massive that they have obliterated hundreds of thousands of square miles of forest, wetlands and permanently damaged rivers.” The company’s Robert-Bourassa dam on La Grande River, for example, impounds a 1,000-square-mile reservoir.

She doesn’t think hydropower generated from these large projects and exported to the United States should count as green or renewable.

“You can’t say that just because the water comes from the sky and ends up in their storage reservoir where they hoard it, completely altering the natural flow of the rivers, that the electricity that you produce is renewable,” she says.

Much of this dam building in Canada has also taken place on the ancestral lands of Indigenous nations. Hydro-Québec says they have signed 40 agreements with Indigenous communities related to hydropower development and transition in the last four decades.

But roughly a third of Hydro-Québec’s power comes from Innu, Atikamekw and Anishnabeg traditional territories, according to the First Nations communities, who have sought settlement for decades with the company.

That history hasn’t been lost on tribes in the United States, either.

Most recently the Penobscot Nation came out against the Maine transmission corridor. In a July 22 letter to the Army Corps of Engineers, the tribe’s Chief Kirk Francis called for a thorough environmental review and said the agency, “must consider not only the Maine impacts, but also those in Canada,” including the harm to Indigenous people.

The letter also cited the corridor’s potential to harm brook trout habitat and endangered species such as roaring brook mayfly and northern spring salamanders.

The forest is an important deer wintering habitat and is known for being some of the best brook trout habitat left in the United States. “From a perspective of a brook trout, you just couldn’t put this line in a worse place,” says Bennett.

Approval Process

Despite all these issues, the project has already received most of the approvals it needs, including from the Maine Public Utility Commission, the Land Use Planning Commission and the Department of Environmental Protection.

The issue was set to come before Maine voters in November, when a ballot initiative could have halted the project. But in August the Maine Supreme Judicial Court ruled the referendum unconstitutional, deciding voters don’t have the authority to override the Public Utilities Commission’s decision.

Even though the battle over the issue didn’t make it to the ballot on Election Day, it was still costly. Political action committees backed by Central Maine Power and Hydro-Québec spent $19 million fighting the effort — a feat enabled by a loophole in Maine law that allows foreign entities to contribute to ballot initiatives.

The project does still need approval from the Army Corps of Engineers and the issuance of a “presidential permit” from the Department of Energy because it crosses an international border. Decisions on both could come soon.

The Corps didn’t require an environmental impact statement, only a less-stringent environmental assessment, which is being prepared by Central Maine Power. Documents obtained by the Natural Resources Council of Maine, through the Freedom of Information Act, found the Corps still had some questions about the touted greenhouse gas and other benefits of the project.

Opponents of NECEC are also challenging the approval on two legal fronts. The first is an appeal of the state’s Department of Environmental Protection permit decision.

A second legal challenge from opponents, including several state lawmakers, concerns a piece of public land the state’s Bureau of Public Lands leased to Central Maine Power back in 2014 that is now being used for the transmission line project.

The lawsuit contends that the Bureau did not get the necessary two-thirds vote from the legislature required for leases that “substantially alter” public lands. Furthermore, it argues, Central Maine Power would have needed to have the Public Utilities Commission permit in hand first, before applying for the lease. But when this lease was granted, the transmission project hadn’t yet been proposed.

Whether these lawsuits can put the brakes on the project isn’t clear yet. Project opponents are also considering another ballot initiative for 2021 that would require a two-thirds vote in the state legislature to approve new transmission lines and to use public lands for the projects — and it would retroactively cover projects from the preceding six years.

Bennett thinks that instead of pushing a corridor through Maine, Massachusetts should do more to develop its own renewable energy resources.

Remember Cape Wind? The offshore wind project, first proposed in 2001, could have brought 468 megawatts to the state but was shot down by a barrage of litigation, including suits from wealthy residents who didn’t want their view obstructed.

“Part of the problem here is that Massachusetts has been real slackers in terms of building wind in their own state,” says Bennett. “They need to build onshore and offshore wind, and to stop exporting responsibility for generating their own clean energy to other people who sometimes don’t want it.”

His organization wants to see more clean energy in the region, but this project doesn’t fit the bill.

“This isn’t a case where, you know, we all have to kind of suck it up and take the impacts in order to help the climate — that’s bogus,” he says. “This is simply a for-profit venture that will have no climate benefits and will have terrible on-the-ground environmental impacts for Maine.”

Correction: The width of the transmission corridor through the North Woods would be 54 feet, not 150 feet as first proposed.

Coming soon: Part 2 of our series on climate change and hydropower.

![]()