What would you do if an energy company declared that it planned to build a natural-gas pipeline through your property, your community, and the surrounding countryside?

For many residents of Virginia and West Virginia, that question became a reality in 2014 when a consortium of energy companies announced plans to build the Mountain Valley Pipeline, using eminent domain to claim a wide swath of public and private lands.

Residents and activists spent the next 10 years fighting the project. In the process, they connected with each other, built community resources and mutual-aid networks, and inspired other activists around the country.

Residents and activists spent the next 10 years fighting the project. In the process, they connected with each other, built community resources and mutual-aid networks, and inspired other activists around the country.

They lost the fight — the pipeline started transmitting gas in 2024, two years after West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin struck a deal with President Joe Biden to help push the climate legislation known as the Inflation Reduction Act over the finish line.

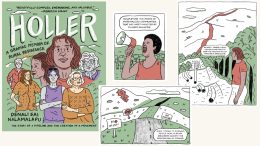

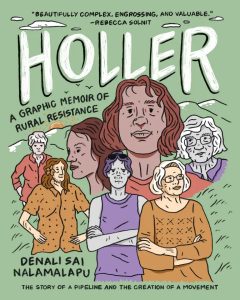

But their experiences offer valuable lessons for other communities, says activist and artist Denali Sai Nalamalapu, who spent several years involved in the battle against the Mountain Valley Pipeline. Nalamalapu has now collected six residents’ stories — including a single mother, a photographer, a teacher, and an Indigenous seed keeper — in the new book, Holler: A Graphic Memoir of Rural Resistance (Timber Press).

The Revelator recently sat down with Nalamalapu to discuss the graphic novel, the ongoing climate fight, the problem of “false hope” narratives, and how to find balance in a worsening crisis. (This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.)

Could you put this book in the context of your greater activism?

I’ve been a climate organizer since I graduated college in 2017. I was living on Borneo in Malaysian territory through a Fulbright grant and was surrounded by the impacts of palm oil plantations and rainforest destruction. I was thinking a lot about how complicated environmental destruction and climate change are, even though our impulse is often to simplify things. That made me want to go into climate organizing and climate communications, where I became very interested in who was being left out from the narrative and who we weren’t speaking to, because climate communications can be very scientific and can be specific to Western audiences.

Ultimately I landed in the Mountain Valley Pipeline site in Appalachia in 2021.

One of my big questions there was, where could we be more accessible and who are we leaving out of our audience, because the audience could be so big with a fossil fuel pipeline during this point in the climate crisis.

And you carried that over to the book, where you interviewed a range of people who seem like the people who would often get ignored in these narratives. Are you hoping that readers have six opportunities to see a little something of themselves in that book?

Yeah, that’s a big part of why I wrote the book and how I wrote it. In talking to people like Karolyn Givens, whose story is featured in the second chapter, I was struck by how many of us have grandmothers who are nurses or other people in our family who worked in the medical field. I hope that people pick up the book and see someone like Karolyn or Becky Crabtree, who is a science teacher. So many of us have teachers in our lives.

And they can see how these ordinary people use the skills that they already had to be part of resistance to a powerful, giant, fossil fuel project, even though they weren’t career activists.

View this post on Instagram

I’m so taken by the artwork in this book. It’s pared down, a little cartoony. But the linework is very evocative and reveals the destruction and the pain on these people’s faces. Did you learn anything through drawing it in this approach?

I always felt like my path as an artist was too winding, like I didn’t have necessarily a specific medium that was my thing. I was just always obsessed with making art, whether that was painting portraits most recently, or in my very early days of childhood that was cartooning and comics. And the thing that surprised me is that all those different journeys —through ceramics and printmaking and cartooning and portraiture — did come together in this large project.

For example, I spent so much time during the pandemic in oil and acrylic portraiture, so I learned a lot about the shadows on people’s faces. There’s not a lot I could do to really make those emotions on people’s faces be super realistic, because by design they weren’t supposed to be. But shadows are one way to connect them to the way I see people.

View this post on Instagram

Now, this is a fight that did not pan out. A lot of people and land faced a lot of destruction. The pipeline still pretty much went through as planned. But there’s still an important message you’re trying to convey here about hope and about continuing to fight these pipelines. Can you speak about that?

I feel that at this point in the climate crisis and in the climate movement, we can’t just be looking for 100% crystal-clear wins, because the reality is that our future will be imperfect — especially when we think about how reluctant and combative leaders and the United States have been to retiring fossil fuels. And when we look at the way capitalism has such a tight grip on our world, I think that it’s important to tell stories that have more complexity than just “we won.”

And the Mountain Valley pipeline is one of those stories. Being part of the movement, I saw every day that it mattered that we fought against the pipeline for 10 years.

There were some anecdotes that suggested that the Atlantic Coast Pipeline getting canceled was connected to the fierce direct-action movement against the Mountain Valley pipeline. The Atlantic Coast developers didn’t want to put up with that degree of resistance.

And there are many other ways to look at the community that was built, the mutual aid networks that were built around monitoring water quality across the route, the ordinary people who learned about our regulatory agencies and how we can advocate for planetary well-being and community well-being in those agencies.

All these things felt very important in the day-to-day and I think, looking back, are important to remember. Because I think we lose out if we just have complete 100% happy hope or complete despair. There’s so much in between, and I hope that this book can contribute to all of the stories and possibilities in between.

There are now hundreds of smaller pipelines in the works or in the planning phases around the country. People in those communities could learn from this book.

We’re definitely seeing that with the Mountain Valley Pipeline Southgate site, where many people living on the main line still support the resistors on the extension that MVP is trying to build into North Carolina.

View this post on Instagram

Generally, the fossil-fuel industry has changed its playbook from the massive pipelines we saw 10 years ago to much smaller pipelines.

I think one thing that feels important and makes me feel hopeful as an activist is that many people see the connections between all these pipelines, all these small projects and the banks and insurers behind them. And people are seeing more clearly how capitalism is behind this, and corporate greed is behind this.

There’s certainly a lot of work left to do, and a lot more people to share the message with. But the reality of this massive pipeline going through — and then MVP pursuing a tiny extension along with a bunch of other smaller projects in the southeast — is that these movements are quite connected and the pipeline fighters are learning from each other.

I hope that this book can be part of people’s journey, whether they’re shifting from the mentality of fighting big projects to fighting many smaller projects, or they’re newer to the climate movement and they’re trying to learn about the history of the fight and all the possibilities that are before them in terms of how they resist.

You’re on tour now. You’re doing some signings and some events. What kind of reaction are you getting?

I started writing this book before the MVP was greenlit and completed. I didn’t know how it would change the reception that it was a completed project. But I’m really pleased that people are still willing to learn from the people in the book and the overall story, even though the project was completed.

I have also really enjoyed meeting expat Appalachians who feel so connected to the region and to the history of fossil fuel resistance.

Every place I go, I meet people who are very connected to these mountains, where the Appalachian Trail runs and where people have either childhood memories or hiking memories. That’s a beautiful thing, because I live in Southwest Virginia because of my love for the mountains.

And then, more broadly, I’m hearing from people about this moment.

One thing that I’m hearing is that people are very disinterested in false hope and people talking down to them about how “everything’s going to be okay.” Because we’re all seeing so clearly that things are not okay and that they are getting much worse, and that what’s happening on the federal level is very violent and is hurting people.

So, what comes next? Are you still in the fight? Are you looking at other stories to tell? Or are you just working on trying to help people in their communities right now?

I really enjoy a life of balanced organizing and creative work. I think after the November election and after the Mountain Valley pipeline was greenlit and then constructed — and the gas is flowing now — it became clear to me that two of the most important levers of power we have are our local elections and our mutual aid networks.

In terms of organizing, that’s what I’m really interested in: how we can elect climate champions on the local levels, given the clown show that is the federal government right now. And then I think it’s important that we know our neighbors and develop mutual aid networks and are prepared for storms like Hurricane Helene or other disastrous floods and wildfires.

One thing I learned working on a pipeline site that we lost is that it can be a precarious thing to anchor your hope in one action. Something that’s important to me is that I’m working on local elections near me and around the country, involved in my mutual aid networks, doing creative work — just having a diversity of things I’m doing that address climate change in different ways that are rooted in community. Right now I’m thinking about that notion of hope and what it means to actually believe in a possibility of a climate future — or of a better future in a way that doesn’t feel like it’s diluting oneself or diluting the reader in terms of false hope.

I find that having creative projects ongoing as I organize is a helpful way to keep up my energy. Otherwise, I get too pigeon-holed in one part of the work, and it’s easy to feel more despair.

Specifically, I’m interested in creating more stories for younger audiences, because I think we can never have enough support and stories for young people who are figuring out the world they’re going to enter.

Previously in The Revelator:

Building a Flock: How an Unlikely Birder Found Activism — and Community — in Nature