“Turning Points” examines critical moments in environmental history when change occurred for the better — or worse.

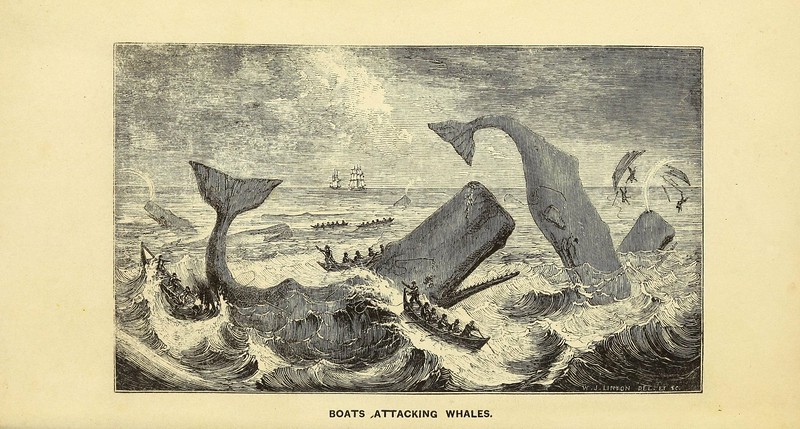

The origins of commercial whaling trace back to the Basques of the 11th century. It’s a bloody history, one emblazoned in many peoples’ minds by the later image of Herman Melville’s tortured Ahab relentlessly hunting the beleaguered Moby Dick.

But this semi-Romantic image of 19th century whalers silently sweeping across the globe on unfurled sails in search of profit and adventure belies a truth.

The fact is that the decimation of whales occurred not in those days of the Industrial Revolution but in the mid-20th century. It was during the age of petroleum, not of kerosene, that whales were driven to near extinction by modern pelagic fleets that employed exploding harpoons, helicopters, sonar and stern-slipway factory ships.

International bodies, scientists, politicians and conservationists attempted to save whales from disappearing as early as the 1920s. Their orthodox efforts — employing diplomacy, science and reason — failed dismally. Instead, it took an unconventional troop of 1960s iconoclasts to rescue whales from the brink of annihilation.

International bodies, scientists, politicians and conservationists attempted to save whales from disappearing as early as the 1920s. Their orthodox efforts — employing diplomacy, science and reason — failed dismally. Instead, it took an unconventional troop of 1960s iconoclasts to rescue whales from the brink of annihilation.

With appeals to the heart, whales became a unifying symbol of not only a global environmental movement but also of a rejection of cultures of violence, war and death. It was a fleeting moment in time when traditional institutional hegemonies were vigorously questioned. By placing whales in the larger context of an antiestablishment appeal, commercial whaling effectively ended in 1986.

Perhaps the whale’s peculiar path to redemption offers a way forward for our planet.

The Whaling Club

To understand this, it helps to first understand how science and hard data failed whales, and that begins with the International Whaling Commission.

The International Whaling Commission was the first global body dedicated to the rational management and conservation of a biological species. Formed at the behest of the United States in 1946, the IWC was a governing authority made up of the world’s 15 major whaling nations. The commission’s objective was to regulate whaling to maximize “the interests of the consumers of whale products and the whaling industry.”[1]

Treating whales as a mere resource put the animals in a precarious position.

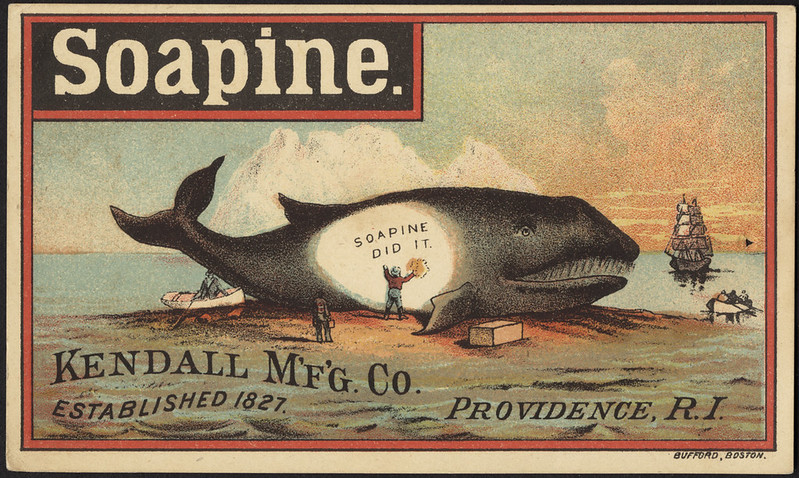

Despite the supplanting of whale oil as lamp fuel with the discovery of petroleum (1859) and electrical lighting (1879), human ingenuity kept finding new uses for whale “products.” Throughout the 1960s, nearly 70,000 whales were slaughtered annually for meat, margarine, soap, animal feed, fertilizer, ivory knick-knacks, perfume, liquid wax and high-end industrial lubricants.

Emerging science made it clear that such butchery was unsustainable.[2]

Genuine concern for rapidly declining whale populations spurred Arthur Remington Kellogg, one of the earliest scientists to rigorously study whale biology, to become the force behind the establishment of the IWC. A master diplomat with many friendships and connections across governments, academia and industry, Kellogg understood that until that point legal norms treated any international common-pool resource as an open-access one. In other words, sovereign governments always enjoyed unhindered authority when making decisions about their use of these common resources, including whales, which mostly swam in international waters and therefore could be hunted without restrictions.[3] Kellogg organized the IWC so that whale science would nudge, not confront, nations to relinquish some of their freedom on the high seas. It would be difficult, but he believed scientific discourse would eventually help IWC members see the wisdom of maintaining a sustainable fishery.[4]

To accomplish this reasonable expectation, the IWC established two important yet contradictory permanent committees. The Scientific Committee, composed of leading cetologists from around the world, was charged with reviewing catch data and making recommendations on research needs, yield quotas and rates of stock depletion. The Scientific Committee then sent recommendations to the Technical Committee, which “consulted” and revised the report for final IWC approval. For the next 20 years the political appointees on the Technical Committee consistently ignored Scientific Committee recommendations in favor of the short-term interests of whaling nations. Promoting stable and resilient whale populations was of little concern.

Kellogg was not a Pollyanna. He and other prominent cetologists realized that science was never going to be the primary driver of the actions of the IWC. But they also believed that realpolitik compromises, like knowingly having the Scientific Committee recommend quotas that were too high, would eventually win them influence in the IWC.[5] Better to be insiders pushing the IWC toward reform, they reasoned, than scientific rabble-rousers causing recalcitrant reaction.

Unfortunately, the dream of being influential insiders would die hard as Kellogg and other well-meaning scientists were consistently politically outmaneuvered by cynical whaling states.

Enter the Pied Pipers of Whales

Without doubt the 1960s are mythologized. Yet the decade’s counterculture movement fundamentally changed the world in radical ways. Protests against capitalism, consumerism, authoritarianism, racism and war swept across the globe from Tokyo to Paris and Prague, and from Mexico City to Birmingham and Washington, D.C.

Coming out of this antiestablishment zeitgeist was neurophysiologist John C. Lilly. His role in the campaign to end international whaling cannot be overstated.

An LSD-dropping free-love practitioner, Lilly conducted pioneering bioacoustics research investigating cetacean intelligence and the possibility of interspecies communication. His ethically questionable and unorthodox experiments led to two hugely popular if scientifically dubious books, Man and Dolphin (1961) and Mind of the Dolphin (1967). Lillyists, as his disciples came to be known, believed that the weightlessness of ocean-dwelling mammals permitted them to overcome the terrestrial separation of the mind and body. This weightlessness, he wrote, allowed cetaceans to attain the highest level of consciousness, one free of alienation and violence. Bioacoustics would unlock the secrets of cetacean communication and, more importantly, would be the means by which cetaceans could then teach humanity to reach superior consciousness.

Lilly’s message found a very receptive audience into the 1970s. In particular he influenced Scott McVay, a Princeton graduate in English. Trained in bioacoustics by Lilly, McVay, with the help of Roger Payne, became the first person to record the haunting and mysterious phonations of humpback whales in 1967.

These spectrograms soon captured the world’s imagination. They inspired music, cinema, literature, art — even NASA. It was a staggering achievement that eclipsed Lilly’s original ideas.

For better or worse the recordings effectively transformed whales into totems, dichotomizing humans into those who protected whales and those who did not. For the first time whaling nations faced real social condemnation. Empathy-driven boycotts, protests and violent confrontations with whalers produced tangible political pressure to not just maintain sustainable fisheries, but to ban whaling altogether.

Conflict With Science

The world of respected academic cetology rejected Lilly and his band of outsiders with prejudice.

In a 1961 review of Man and Dolphin, James W. Atz, an ichthyologist at the American Museum of Natural History, dismissed Lilly for not presenting a “single observation or interpretation that could withstand scientific scrutiny.” For Atz and other elite sages it was important for scientists “to have a rational view of animal life,” and he lamented that “Dr. Lilly … felt called upon to put himself so prominently in the public eye.”[6]

Nothing captures the disconnect between the conservative world of academic scientists and an increasingly sympathetic public ready to save whales more than Prof. G. Carlton Ray’s (an expert in cross-disciplinary coastal-marine research and conservation) hostile reaction to McVay’s whale recordings in 1971:

I don’t find it very relevant to hear that whales produce music. Cock-a-doodle-doo produces music too. Whales are smarter than chickens, but it is not relevant… Neither is it relevant to say that whales have a complex social life. So do all the animals, including cows that we eat. The point is to talk good international research and management sense.[7]

But here’s the reality: Hyperrational, data-driven quantitative science like that advocated by Ray simply failed to influence society, culture and politics, even at a time when humanity was ready to radically question authority. It took the scientific taboo of empathy-driven anthropomorphism to compel sovereign governments to surrender some of their authority to make unilateral decisions about the use of open-access resources.

By 1974, 17 anti-whaling environmental groups with millions of members organized an international boycott of Soviet and Japanese products.[8] World opinion and economic pressure was building on the two countries most committed to whaling. The Marine Mammal Protection Act was passed in 1972.[9] Then, in 1978, the United States enacted the Pelly Amendment, which mandated economically crippling restrictions on imports from countries that violated IWC regulations or any international endangered or threatened species program.[10]

At last, legislation like the Pelly Amendment provided the IWC with indirect yet real regulatory power, which it had always lacked. Because of these and many other grass-root and legislative efforts, the IWC (which still exists) was finally able to ratify a 10-year moratorium on commercial whaling in 1986. Since then only Japan and Norway have resumed limited commercial whaling.

Politics, Our Planet and Songs Whales Sing

As historians Michael Brenes and Michael Koncewicz have noted, the demands of many contemporary and 1960s activists have been rejected and “labeled extreme” by political and social centrists. Yet historically, it’s these “extremists” who have pushed “the ideological boundaries of liberalism,” and driven progressive political and social change.[11]

In these bleak neoliberal and authoritarian times of mass extinction, we desperately need new summers of love like those that inspired change in the 1960s. Today’s warriors fighting to stop our slide toward ecocide will find in the story of whales that it was outsiders/extremists and their uncompromising appeals to the heart that smashed flawed and immoral political structures.

And like Lilly and other nonconformists of the 1960s, today there are persons and groups who are ready to push the envelope of the status quo and test what is politically and socially possible.

For example, desperate protests forced the shutdown of the Dakota Access pipeline in 2016/17 and captured media attention from around the world. People traveled for hundreds of miles to join the protest camps, often spending months there standing up for the cause. But timid centrists at the time, like Hillary Clinton who was running for president, declined to support the demonstrators.[12] As with whales, a disassociation existed between the public and policymakers who failed to recognize that American society was still capable of being roused into action because of basic human empathy. Clearly, the sight of brutal police violence against peaceful protestors from the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and their many allies aroused the public’s conscience against the project.[13]

Then there’s the tragic story of Tahlequah and her dead calf, of the endangered Southern Resident killer whale family, in 2018. Like McVay’s recordings of humpback whales, the spectacle of Tahlequah carrying her dead child for weeks emotionally galvanized the world.

In an overwhelming response to the Seattle Times asking readers to recount their reaction to Tahlequah’s heartbreaking story, the universal sentiment was one of staggering lachrymose devastation: “I can’t stop crying. I can’t sleep,” said one respondent.

“I have been deeply affected by this,” wrote another. “As a mother of young children, I find myself moved by her grief and behavior… I am now extremely concerned about her health and well-being. I have called our elected officials’ offices to plead for immediate action to help SRKW population.”[14]

This spiritual anguish also had concrete political repercussions. In March 2021 Rep. Mike Simpson of Idaho, a Republican, unveiled a proposal to breach the Snake River dams that have choked off the Southern Residents’ salmon food supply. His proposal is deeply flawed, but signals an awareness of the broad popularity of the deeply charismatic orcas.

Many other species of whales continue to be in grave danger of extinction. Today it’s not so much the cruel harpoon that threatens them as ocean warming and acidification, ship strikes, plastic, noise, trash, fishing nets and pollution.

Here’s what else has changed: Thanks to advances in whale science, we now know they have complex and highly evolved clan and family structures. Their sophisticated cultures give us even more reasons to cherish these Leviathans of ocean storms, tides and depths.

It may not pass orthodox scientific and political muster, but it’s time for us to try to imagine what whales and other living beings think of our stewardship of the natural world and to harness the noblest of human impulses — mercy. Modern Western civilization, born out of the Enlightenment, wedded to the notion of rational reform, dismissive of what it deems as “irrational,” and attracted to mechanistic problem-solving, must dare to be profoundly different.

It worked to end whaling. It can and must work again.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.

[1] International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling with Schedule of Whaling Regulations, December 2, 1946, Article V, Paragraph 2.

[2] 1956 IWC meeting: IWC/8/13, 108-9.

[3] Elliott, Gerald. “Fishing Control—National or International?” The World Today 28, no. 3 (1972): 133-38.

[4] D. Graham Burnett, The Sounding of the Whale Science & Cetaceans in the Twentieth Century (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012), 372-373.

[5] D. Graham Burnett, The Sounding of the Whale Science & Cetaceans in the Twentieth Century (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012), 372-373.

[6] D. Graham Burnett, The Sounding of the Whale Science & Cetaceans in the Twentieth Century (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012), 590.

[7] Grieves, Forest L. “Leviathan, the International Whaling Commission and Conservation as Environmental Aspects of International Law.” The Western Political Quarterly 25, no. 4 (1972): 721.

[8] https://www.nytimes.com/1974/06/20/archives/japanese-and-soviet-whaling-protested-by-boycott-of-goods-85-of.html

[9] https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/topic/laws-policies#marine-mammal-protection-act

[10] https://www.fws.gov/international/laws-treaties-agreements/us-conservation-laws/pelly-amendment.html

[11] https://www.thenation.com/article/politics/left-history-democratic-party/

[12] https://www.commondreams.org/news/2016/10/28/what-crock-clinton-breaks-dapl-silence-statement-says-literally-nothing

[13] https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/sep/12/north-dakota-standing-rock-protests-civil-rights

[14] https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/i-have-not-slept-in-days-readers-react-to-tahlequah-the-mother-orca-clinging-to-her-dead-calf/

![]()