When you first step outside into 115-degree weather, it feels surprisingly good — like a full-body bear hug from a long-lost relative.

That lasts about two or three seconds.

After that, you start to really feel the heat. Your skin instantly goes dry, only to dampen again as your sweat glands jump into overdrive. Within a few more seconds, you’re sweating in places you’d forgotten about. Your clothes feel heavier with moisture, even as the first wave of it is whisked away from your body.

Then you feel it in your lungs and eyes. Breathing becomes a little bit harder, and blinking does nothing to alleviate the painful dryness.

Your muscles react soon after that. Those first few seconds of warmth fooled them into thinking they could be active and strong; then they give up on that idea in a flash, leaving you wobbly on your feet. If you’re going to do anything, your brain tells you, you’d better do it quickly.

You don’t want to do anything, though — except find relief.

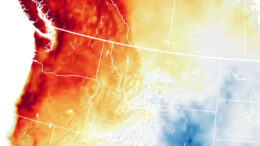

This was life under the heat dome in the Pacific Northwest this past week. Late June temperatures in the Portland region typically stay in the mid-70s. Not this year. Maybe not any year ever again.

This was life under the heat dome in the Pacific Northwest this past week. Late June temperatures in the Portland region typically stay in the mid-70s. Not this year. Maybe not any year ever again.

My family, it turned out, was both lucky and privileged enough to make it through the worst of the heat. We’re in one of the rare homes in the region that has central air conditioning, and we both work at home. Other than taking the dogs outside a few times a day, we could stay indoors in relative safety.

We still felt the heat, though. By the time temperatures reached their apex on June 28, the sun had been beating down on our townhouse for 10 hours. The walls and windows radiated with heat. We couldn’t drink enough water. Brain fog and lethargy settled in.

That was nothing, though, compared to many of our neighbors. Throughout the region, people suffered under the brutal blaze. Hospitalizations soared, and dozens of people died (hundreds, counting all the way into British Columbia). Cooling centers provided some relief, although the fear that they’d also serve as pandemic hot spots kept people from fully relaxing.

Infrastructure, all of it built for your typical Pacific Northwest summers, deteriorated too. Roads buckled. Electrical cables melted. Power grids crashed. Crops died. Stores closed to avoid the worst of the afternoon heat. The trees on my street turned brown along the edges and shed many of their leaves, the sudden shock too much for their systems.

We knew it was coming. Or, at least, we should have known. The warnings had been in place for years. Our governments, utilities and corporations — not to mention our families — should have prepared.

We all failed. Climate change came for us after all.

But in a sign of…I don’t know, progress?…the mainstream media mostly covered this heatwave as an event inspired by and typical of climate change, a rarity when it comes to extreme weather events. Coverage of another June heat event in Colorado, for example, mostly failed to mention climate change. This time, though, in article after article and broadcast after broadcast — not every instance, but enough — experts renewed their warnings that this is the shape of things to come. That we need to adapt. That we need to prepare. And that we need to act to ensure this doesn’t become the new normal.

But will we?

That question should haunt us. And we should demand action. Our leaders should sit up every morning and think “What can I do today to help make sure this doesn’t happen again tomorrow?”

They probably won’t, of course — at least, not at first — but we need to keep bringing the heat.

Because heat either kills or motivates us to get out of danger. Those are the only two options. Standing still in the face of climate change is a fool’s game — and a luxury we don’t have anymore.

![]()