Some people call the Great Plains “flyover country.” Outdoor enthusiasts sail above it on the way to the mountains of Acadia, California’s redwoods or Utah’s red rock. Conservationists, too, have bypassed the region. Few big public preserves or parks exist there.

Ecologist Curtis Freese hopes that changes.

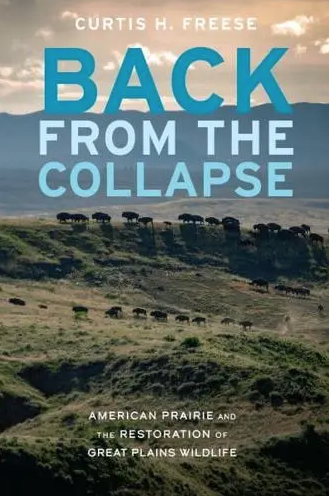

His new book, Back From the Collapse: American Prairie and the Restoration of Great Plains Wildlife, is a call to protect and restore the northern Great Plains and the biodiversity it once held in great numbers. That includes swift foxes, beavers, river otters, bison, elk, pronghorn, black-footed ferrets, grizzly bears, wolves and numerous species of grassland birds.

Some of that work is already underway. In 2002 Freese helped launch the nonprofit American Prairie, which aims to establish a preserve of 3.2 million acres in northeast Montana where the mixed-grass prairie has escaped the wrath of the plow that uprooted many other areas of the Great Plains. The group’s about halfway to its goal, with nearly 600,000 acres of deeded lands or leased public lands, along with 1.1 million acres of the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge.

“The region offers our best chance to reassemble the native wildlife community within a vast reserve large enough to preserve the ecosystem to its fullest potential,” he writes in the book.

The Revelator spoke with Freese about the biodiversity of the northern Great Plains, what it would take to restore native wildlife, and what obstacles remain.

Why do you think the Great Plains is often neglected when it comes to conservation?

I think there’s two main reasons. One was that compared to wetlands or forests or mountains, agriculture could simply get a quick jump on colonizing the Great Plains. You didn’t have to drain the wetlands, you didn’t have to clear the forest, you just opened the gates and let the cows out. It was all right there, ready to eat or plow.

Secondly, the turnover from 1870 to 1895 was dramatic. There had never been such a big change in the world so quickly — from an ecosystem where there was nothing but wild ungulates, to one that virtually eliminated all the ungulates and you had nothing but livestock. Because it was eliminated so quickly, there wasn’t a chance for the public to appreciate what had been — to say, “We need a big Great Plains park like Yellowstone.” We never had the chance.

What was the biodiversity of the region like before European colonization brought plows and cows? And how does that compare with what’s there now?

This was one wild, rambunctious system that went through a lot of ups and downs. We had glaciers covering it just 12,000 years ago. In the mixed-grass prairie it’s 110 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer and sometimes it’s -50 degrees in the winter, so you’ve got to be tough to live there. Prairie wildlife exhibits that. Bison don’t need to go to water nearly as much as cows do.

When Lewis and Clark went through eastern Montana [in 1805-1806] they saw more wildlife than any other place in their trip — either to the east or to the west of the Rocky Mountains — all the way to the coast. It was just a remarkable ecosystem that we once had.

Now most of the species are either [greatly diminished] or not there at all, such as the wolf. Wolves now are in the Rocky Mountains of Montana, but back in the 1880s and 1890s, the state put a bounty on them, and every year roughly 4,000 to 6,000 wolves were killed, mostly in the plains of eastern Montana.

Today we’ve got relatively good numbers of deer because people like to hunt deer and they’re not quite so threatening to agriculture. But the elk numbers are highly suppressed because of depredation concerns about crop land, and pronghorn numbers are still down. The bison is simply a fraction of 1% of what it once was.

What’s the potential to be able to restore some of these populations of native wildlife?

What I see in northeast Montana — and what’s great about this ecosystem — is its diversity of habitat. You’ve got the Missouri River running through it. Then you’ve got floodplains and the rugged Badlands-like environment as you come out of the floodplain up into the rolling prairie. And then there are these isolated mountain ranges, like the Little Rocky Mountains, with pine forests. You have this wonderful cross section of habitats that support a great diversity of species. Some only live down in those floodplains. Some live in the rolling prairie, like the swift fox, and others live in the more mountainous and forested areas, like mountain lions.

The diversity of habitat is there, and much of it’s intact, but there’s still a threat of prairie being plowed up and put into wheat and barley. Once you plow it up, that’s the killer threat. Nothing survives very well in a wheat field.

Put bison out there [instead], they’ll double the population every three or four years, no problem. Three of the Indian reservations in the region have bison. Grasslands National Park just across the border in Saskatchewan has bison. But we need to create much bigger herds of bison to mimic what they once did to that ecosystem and support the diversity of grassland habitat by their grazing. So there’s a long way to go in terms of building back the wildlife numbers.

Some, like the black-footed ferret, have a real challenge ahead of them because prairie dogs, which are their main source of food, continue to be poisoned and shot. Another threat is an introduced disease that came decades ago from Asia and is highly lethal to prairie dogs, as well as ferrets.

Others are also going to take some extraordinary effort to bring back. With wolves and grizzly bears, the problem isn’t a lack of food — or as we say, the “ecological carrying capacity” of the environment. It’s the social carrying capacity — people’s tolerance for big predators. We need to have some innovative approaches to enabling these big predators.

What does recovery look like for native grassland birds, many of whom are also declining?

Ecologist Andy Boyce said that recovering birds should be the easiest. They don’t threaten anybody. They move around to find the best habitat. And yet we still have declining bird populations because of three main threats.

One is the ongoing conversion of grasslands to cropland. The problem there as much as anything is the huge farm subsidies that lead to more plow-up and conversion of prairie to cropland.

The second is homogeneous grazing. In rangeland management the idea is to have the cows eat half the grass and leave half the grass everywhere. Uniform grazing. Well, to a lot of birds, that’s the worst outcome because some birds like it grazed down to the ground. Other birds like it not grazed at all. If you’re a five-inch-tall bird, that difference in grass height is like the difference for us of walking through a forest versus the shrubland.

So we need bison, and sometimes fire, to go back and recreate that diversity of grassland habitat, which birds depend upon.

The third one that’s an increasing threat are the new neonicotinoid insecticides, which are shown to be highly toxic to migratory birds and pollinators like butterflies and bees.

What’s needed to boost conservation in the region?

There are three pillars of conservation in the Great Plains. The first is no more sod busting, no more conversion of grassland to cropland.

Number two is the ranching community needs to be much more friendly to prairie wildlife. A lot of ranchers do a good job. There’s a lot of good ranch management going on, but a lot of them don’t. For example, prairie dogs are still much maligned and not tolerated, and they don’t create that much of a problem for ranching. And we also still see bison as belonging behind a fence, which is nuts.

We need to have a new kind of approach to ranching that realizes wildlife like bison, big predators, and small animals like prairie dogs, all have a place. Ranching can provide corridors and safe passage between parks, refuges and reserves for wildlife to move through.

Then third, we’ve got to have big protected areas of a million acres or more. Those are the cornerstone of wildlife conservation, whether you’re in the Great Plains, the Amazon or the Arctic. So we need more places like American Prairie and the Charles M. Russell Refuge across the Great Plains if we want to restore and conserve everything from prairie birds to ferrets to large predators and ungulates.

We’ve got a lot of public lands in the Bureau of Land Management lands and National Grasslands, which are managed by the Forest Service. An act of Congress could convert those into more protected status.

Those places have a multiple-use mandate that includes biodiversity conservation. I think we simply have to provide greater weight to the biodiversity benefits of these public lands that belong to all the public, not just to the ranching communities that graze them. I think we need to have a shift in attitudes about what the best use of these lands is. And I think in a lot of cases, these public lands, the best use is for wildlife biodiversity conservation.

In just the Great Plains alone, we’re spending $10 billion a year to subsidize farming. What if we just took 10% or 20% of that and we apply it to buying and conserving grasslands?

Private lands have got to be part of the solution too, because especially in the southern Plains, almost all the lands are private lands.

A third part of the solution is Tribes. Indian reservations are engaging in wildlife restoration as well.

American Prairie, working with the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge, can serve as a place where the American public can visit a landscape of an endless sky and wildlife with no fences, the likes of which you won’t see unless you go to the African Serengeti now. It used to be the African Serengeti in the Great Plains. Once people experience that, it’s going to be a revelation of, “Yes, we could have this, we could restore it.”

Previously in The Revelator:

Wolves as Teachers

![]()