To most of the world, Great Nicobar Island doesn’t seem to exist. Few photos from this remote, fragile island in the Indian Ocean have been posted online. The citizen science site iNaturalist contains no uploads about the island’s wildlife. The tourism site TripAdvisor only lists one restaurant on the island, with just two reviews.

But India sees the potential for something huge on Great Nicobar: profits.

Great Nicobar is part of India’s Andaman & Nicobar archipelago, more than 800 miles away from the Indian subcontinent. The Indian government has spent the past several years pushing through a controversial $9 billion “holistic development project” for Great Nicobar — including an international port, an airport, a power plant, ecotourism hubs, and a residential township with entertainment zones, shopping complexes, and restaurants.

The project is a brainchild of, and being piloted by, India’s public policy think tank Niti Aayog, which was established in 2015 after the right-wing Narendra Modi government came to power. The execution of the project has been entrusted to a little-known government agency, Andaman and Nicobar Islands Integrated Development Corporation Limited, whose stated objective is to “develop and commercially exploit the natural resources for the balanced and environment friendly development of the territory.” The project comes under the purview of India’s Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, and is also supported by the port and Tribal affairs ministries.

The project, these entities argue, will transform this remote island into a world-class free trade zone like Hong Kong and usher in “development” for its people. At least 10 national and international corporations, including the Gautam Adani-led Adani Ports and the Dutch dredging major Royal Boskalis Westminister, have already expressed interest in the port project.

But environmentalists, ecologists, and conservation experts argue that the project, if allowed to go on as planned, will be “ecocide” and “genocide” for the island and its inhabitants, including hundreds of unique plant and animal species and two Indigenous communities.

“In the past, successive governments had taken a hands-off approach to the Andaman & Nicobar because of its ecological fragility,” says Ritwick Dutta, environmental lawyer and cofounder of the advocacy group Legal Initiative for Forest and Environment. “That has now changed to an intervention-heavy approach that could not only change the ecological character of the islands but also put them at imminent risk.”

The Island

Great Nicobar is the southernmost of the 572 islands that form the Andaman & Nicobar archipelago in the eastern Indian Ocean, where they sit closer to Myanmar, Thailand and Malaysia than to mainland India.

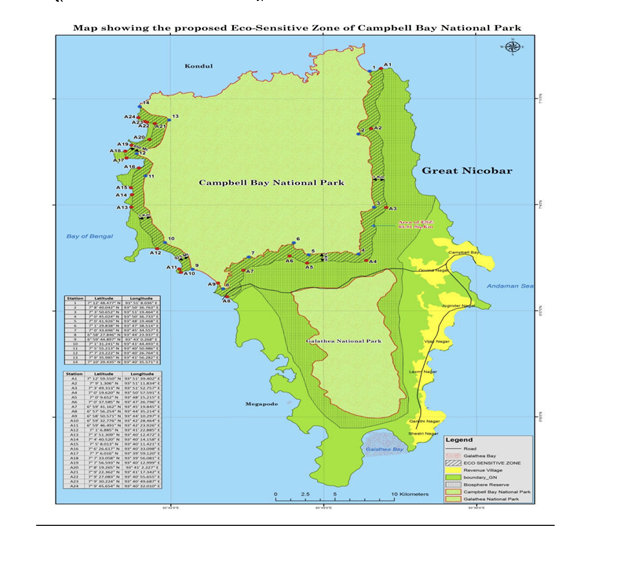

Over 95% of this island, the largest in the Nicobar chain, is a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, within which there are two national parks: the Campbell Bay National Park and the Galathea National Park. Great Nicobar supports diverse habitats, including mangrove forests, littoral (beach) forests, coral reefs, and tropical evergreen forests.

That diversity, coupled with the island’s geographic isolation and tropical wet climate, supports an assemblage of at least 1,767 known animal species and 811 plant species. Of these, many — such as the Nicobar megapode, Nicobar long-tailed macaque, Nicobar scops owl, Nicobar serpent eagle, and Nicobar tree shrew — are endemic to the island and classified as vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List.

In 1956 the government demarcated this entire island as a “Tribal reserve,” carving it out for the sole use of the Indigenous Shompen and Nicobarese peoples and prohibiting encroachment or use in any other form.

The nomadic forest-dwelling hunter-gatherer Shompens, with a surviving population of around 240, are recognized by the central government as a particularly vulnerable Tribal group. In February of 2024, 39 genocide experts warned that the project and its accompanying demographic shifts “will ensure the death knell of the Shompen,” who have thus far managed to limit their contact with the outside world. As a result, “simple contact between the Shompen — who have little to no immunity to infectious outside diseases — and those who come from elsewhere, is certain to result in a precipitous population collapse,” the experts wrote in an open letter to India’s President.

“We have met some families of Shompens living in Great Nicobar and none of them are interested in outsiders coming there and setting up shop or home or factories,” says social ecology researcher Manish Chandi, who has been working among Andaman & Nicobar’s Indigenous communities since 1995. “The southernmost family of the Shompens live close to the Indira Point, the southernmost tip of the island, and their territory extends to the mouth of the Galathea Bay, which is exactly where the port is slated to be constructed. So you can imagine a complete transformation of their lives,” he says.

#UncontactedTribesWeek “Don’t destroy the Shompen”

Take action today 👉 Comment on India’s Ministry of Tribal Affairs’ @TribalAffairsIn posts and say no to the Great Nicobar Development Project which will destroy the uncontacted #Shompen people if it goes ahead! ❌ pic.twitter.com/JfLVjI4Gca

— Survival International (@Survival) June 20, 2024

The 1,094 Nicobarese live along the coasts and depend on fishing, hunting-gathering, pig and poultry rearing, and horticulture of coconut and areca nut. Displaced from their ancestral lands following the cataclysmic Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami of December 2004, they have since been forced to live in government-provided shelters despite appeals to the local administration to be allowed to return.

“The Nicobarese want their ancestral lands back, if not to live, then at least to create their plantations,” Chandi says. “Even if we see it as ‘primitive’ or ‘rural,’ this is the life they have chosen and they want to continue with it to a great extent, of course with the addition of some modern facilities, such as medicine and education.”

The island also supports a heterogenous settler community whose members have migrated to the Great Nicobar from India’s mainland states since the 1960s.

Great Nicobar has spent the past 20 years rebuilding from the 2004 earthquake and tsunami, which claimed at least 3,449 lives (or as many as 10,000 according to some estimates), submerged parts of the coastline by nearly 13 feet, wiped out 27 square miles (6,915 hectares) of forestland, and caused widespread ecological destruction with lasting effects on the island’s biodiversity. It took over a decade for altered coastlines to re-form and mangroves and coral reefs to recover. The island is seismically volatile and has experienced 444 earthquakes over the past 10 years, or one earthquake a week, according to data compiled by researchers at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences.

India’s Playground

This ecologically fragile, biodiverse, and earthquake-prone zone is now the playground for the Indian government’s aspirations to create “an alternative to Hong Kong.”

This massive development will require 64 square miles (166 square kilometers) of land, or roughly 18% of the total area of Great Nicobar. According to data provided by the environment ministry in Parliament, it will wipe out a million trees over 50 square miles (130.75 square kilometers) of pristine evergreen rainforests dating back to the Pleistocene era. Recent estimates by independent researchers suggest that the number may be as high as 10 million trees. The proposed port and parts of the airport and township will subsume the entire Galathea Bay on the island’s southeastern coast, leading to destruction of mangrove forests and coral reefs that create natural barriers against tsunamis and cyclones. The port will also claim 32 square miles (84 square kilometers) of Tribal reserve land, which constitutes half of the project’s designated land.

Protecting this Tribal land is crucial, Chandi notes, because most of the wildlife across the Andaman & Nicobar islands are found in the Tribal reserves. While there are nearly 100 wildlife sanctuaries and national parks across the island chain, most of them have a smaller complement of wildlife. As the largest protected ecosystems in the islands, Tribal reserves are important not only because they are home of the original inhabitants but also because they are crucial repositories of wildlife, he explains.

In addition, the areas adjoining the Galathea and Campbell Bay national parks will be left without any eco-sensitive zones to speak of. These zones are meant to provide an additional buffer or protection to the biodiversity within national parks and wildlife sanctuaries. In 2021 the environment ministry approved a proposal by Andaman & Nicobar administration officials to maintain a buffer zone of just 0 to 1 kilometer (0-0.6 miles) around these parks, meaning they may have no eco-sensitive zone around their boundaries. This is significant given that in a June 2022 order, India’s Supreme Court ruled that each national park and wildlife sanctuary must have a minimum eco-sensitive zone of at least 1 kilometer, though a year later the court relaxed its own order, saying such zones cannot be uniform across the country.

“Having a zero-extent eco-sensitive zone sets a dangerous precedent, since such zones are created to prevent human-animal conflict,” says Dipak Anand, a senior project associate with the Wildlife Institute of India.

Given that the Galathea National Park lies next to the Galathea Bay, it is also likely to experience the fallouts of construction and dredging activity as land is reclaimed for the port and the airport.

Finally, the environmental assessment report conducted for the project suggests that it will increase the island’s population from just over 8,500 today to 350,000 by 2052, placing huge pressure on its natural resources.

A Monkey in the Middle

The consequences, environmental activists say, will be catastrophic for the island’s flora and fauna. Among the species that will find themselves pushed to the brink is the endemic Nicobar long-tailed macaque, already listed as endangered under India’s Wildlife (Protection) Act and vulnerable on the IUCN Red List.

The primate has adapted to a wide range of habitats, including inland and littoral forests, coastal areas, and mangroves. But the 2004 tsunami reduced their population — in 2014, researchers recorded 36 troops, compared to 53 in the pre-tsunami years — and significantly shrank their habitats. With extensive patches of the forests that contain their food destroyed, macaques increasingly ventured into human settlements to explore new food sources. This problem of habitat shrinkage will be further exacerbated by the felling of a million trees under the megaproject.

The EIA report claims that macaques will not be significantly affected and attempts to trivialize the potential harm to the species by describing them as “rampant,” “a pest,” and a “menace in residential areas.” The only mitigation measures suggested in the report are installing canopy bridges to maintain forest corridors and counter habitat fragmentation or, where necessary, relocating the macaques to other islands.

However, as Ishika Ramakrishna, a doctoral candidate at the Centre for Wildlife Studies who works on human-primate relationships, writes in The Hindu, “Macaques have a restricted range, and such drastic alterations to their surroundings and threats to their already limited numbers can increase chances of inbreeding and loss of diverse gene pools. This can be disastrous, resulting in epidemics and loss of reproductive viability that will decimate the population.”

Big Feet vs. Big Footprint

Relocation is also the only conservation measure proposed for a coastal ground-dwelling bird called the Nicobar megapode, a big-footed species also known as the Nicobar scrub fowl.

The birds build mounds of coastal sand and leaf litter to hold their eggs until they are ready to hatch. That makes the megapodes particularly vulnerable to coastline alterations, says K Sivakumar, a former scientist at the Wildlife Institute of India who has been researching the birds since the 1990s. The 2004 tsunami not only wiped out 70% of their population but also battered their nesting mounds, he says, adding the subsidence of the southern tip of the Great Nicobar means much of the bird’s prime habitat has already been permanently lost.

Now the project will shrink their breeding grounds even further. Of the 51 active megapode nests in the project area, about 30 will be permanently destroyed, environmental clearance documents show. That will be a huge blow to the species, says Sivakumar.

One of the birds’ key nesting sites is the Galathea Bay, declared a wildlife sanctuary in 1997. That gave it protected status under India’s Wildlife (Protection) Act, which prohibits most construction activity, hunting, and human habitation in wildlife sanctuaries, national parks, biosphere reserves, and other habitats in the interest of biodiversity conservation. But in 2021 the National Board of Wildlife, the apex body that oversees wildlife-related matters in India, stripped the bay of this protected status, making way for the port as well as the destruction of the megapodes’ coastal habitat.

To compensate for this loss, the EIA report suggests turning nearby Menchal Island, an area of less than half a square mile, into a megapode sanctuary. Sivakumar remains skeptical about the effectiveness of this measure. In a post-tsunami survey in 2006, he recorded only six active nests on Menchal, compared to 203 on Great Nicobar. While still with the WII, Sivakumar recommended that beaches at the Alexandria and Dagmar Bay, the megapodes’ other crucial nesting site in the Great Nicobar, be given protected status to secure the bird’s remaining habitats. The suggestion went unheeded, leaving these areas open to coastal development in the future.

“If the project is expanded to other parts of the coastal habitat, that will be detrimental for the Nicobar megapode,” Sivakumar cautions. “It will be a big question mark on how long and whether we can retain the species in the Great Nicobar, whether it will be 50 or 100 years.”

An Important Site for Turtles

The loss of Galathea Bay’s protected status will similarly threaten a prime nesting site for the world’s largest sea turtles.

Growing up to 7 feet long and weighing nearly 2,000 pounds, leatherbacks travel to these beaches from as far as Australia and parts of Africa during their annual breeding season, says Kartik Sanker, professor at the Centre for Ecological Studies, Indian Institute of Science, who has been part of several leatherback monitoring projects in the archipelago.

As with the Nicobar megapode, leatherbacks lost most of their nests on Great Nicobar in the tsunami, according to Sanker, who says it took over a decade for the beaches to recover and for the turtles to start nesting there again. In 2016 over 400 nests were recorded in Galathea, which was close to pre-tsunami levels. Nearly two-thirds of all leatherback nests on Great Nicobar were concentrated in Galathea, with the rest distributed between the Alexandria and Dagmar beaches.

With the leatherbacks returning to these beaches every year, Sanker cautions that “any permanent alteration to these breeding sites could impact their long-term survival.”

The EIA report emphasizes that the port is to be built on the eastern side of the Galathea Bay, so as not to disturb the leatherback nests that lie on the western flank. But given the scale of the project, Sanker says very little of the beach will likely survive for the leatherbacks to continue nesting in. Also, “any disturbance in the form of light and noise tends to be a deterrent for leatherbacks. Even if they do come and nest, hatchlings will get disoriented in the light and may end up going towards the land rather than the sea,” he explains.

These impacts, the EIA report claims, could be mitigated by suspending construction at night during turtle nesting season, dimming lights in the port area, and reducing underwater noise. Once the port becomes operational, the plan is to monitor the movement of ships to avoid collision risks, install deflectors to keep turtles away from the path of suctioning equipment, and establish hatcheries to ensure the survival of hatchlings. In addition, the project proposes a leatherback sanctuary of about 5 square miles (14 sq km) at Little Nicobar, which had about 200 nests as of 2016. But activists say these measures are either ineffective or grossly inadequate to counter the threat to the leatherbacks’ largest nesting site in India.

Birds in Plight

Noise, light, and habitat loss will also take a toll on the island’s bird diversity.

Great Nicobar’s wetlands, located at the intersection of the Central Asian and the East Asian-Australasian bird migratory flyways, offer sanctuary to hundreds of migratory birds. This is in addition to endemic species such as the Nicobar scops owl, Nicobar sparrow hawk, Nicobar serpent eagle, Nicobar parakeet, Nicobar imperial pigeon, and Nicobar jungle flycatcher.

The EIA acknowledges that the loss of trees will affect the region’s birds but claims that “the impact will be limited as most of the faunal species will be able to relocate to other areas where the vegetation is significant.” For the territorial Nicobar owl, the EIA assures readers that trees with their nesting holes in the project area will be identified, geo-tagged, and “safeguarded as far as possible.”

But “even if scores of India’s finest birdwatchers were to work year-round to document all actual and potential own nesting sites, it would be hopefully unrealistic to survey one million trees (some as tall as 45 m) to identify the owls’ nesting holes,” Pankaj Sekhsaria, a member of the environmental action group Kalpavriksh, recently wrote in the magazine Sanctuary Asia. Sekhsaria has been working on issues of the Andaman & Nicobar Islands since the 1990s and has recently curated a book titled The Great Nicobar Betrayal on the proposed development project.

Authoritarian Approaches

Such half-baked mitigation measures aside, approvals granted to the project demonstrate a disregard for existing regulations and processes.

For more than a year now, India’s environmental court, the National Green Tribunal, has been hearing petitions and counterarguments on the merits of the transshipment port. Several petitioners have challenged the project for violations of environmental and coastal regulations and failure to comply with environmental clearance processes, a charge that the environment ministry is currently defending in court.

The judicial process, thus far, has not been encouraging. In an initial hearing in April last year, the green tribunal said it would not interfere with the forest and environment clearances granted to the project even as it appointed a committee to look into certain “unanswered deficiencies” in the clearances. In an obvious conflict of interest, the committee is made up of members of the very same agencies involved with the project, namely NITI Aayog, which has conceived it, ANIIDCO, which is implementing it, and the environment ministry, which has signed off on it. Predictably, a year later, this committee concluded that the port project could go ahead as planned.

“We have no idea how the high-powered committee has come to any conclusion, because that report is not in the public domain,” says Debi Goenka, executive trustee of the Mumbai-based nonprofit Conservation Action Trust, one of the entities that challenged the project in the courts. The Trust had filed three petitions before the green tribunal, challenging the forest and two environmental clearances. “Our three petitions were dismissed by the tribunal when our lawyer was not present in court, without giving us a hearing,” Goenka says. “That was one of the grounds for a fourth petition we filed in the Calcutta High Court. That’s still pending,” he adds.

One of the remaining holdups of the project, and one that is currently being contested in India’s environmental court, is that parts of it will lie in areas where major development activity is prohibited under India’s coastal zone regulation. According to its provisions, areas with mangroves, corals and coral reefs, turtle- and bird-nesting grounds, among others — all of which can be found in the demarcated project area — are deemed ecologically sensitive and classified as Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ)-1A, where minimal construction activity is allowed.

Indeed, the Andaman & Nicobar coastal regulatory body had earlier classified parts of the site where the port is slated to come up as a CRZ-1A zone. Recently, as environmental bodies challenged the project in court, the national coastal management body conducted a fresh survey and decided that the same areas come under a lesser-protected category, CRZ-1B, the area between high tide and low tide lines, where construction is permitted.

However, as Conservation Action Trust’s Goenka explains: “The government’s own documents, the EIA report, and whatever studies they have furnished for clearance, indicate that there are thousands of coral colonies in the areas that they are going to reclaim and dredge for the port project. Per the CRZ notification, if the site has corals, it automatically becomes CRZ1A, and you cannot build a port there, you cannot destroy the corals. That will be an offense under the Wildlife (Protection) Act.”

What’s more, Sekhsaria points out, the project was cleared with unprecedented haste by India’s Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change, despite its magnitude and potential far-reaching consequences. The request for proposals for the project, preparation of a feasibility study, release of a draft and final EIA reports, and granting of environmental clearance by the ministry were accomplished in just two years. The draft EIA was based on just four days of surveys, even though large parts of the island are impenetrable forests and difficult to access. The ministry invited comments on the EIA from stakeholders and environmental groups, but the final report was published three months later without accounting for the concerns raised on ecology, biodiversity, rights of Indigenous communities, seismic volatility, and disaster vulnerability, Sekhsaria says.

The process of obtaining the consent of Indigenous communities for the project was also replete with misinformation and inconsistent information. In November 2022 members of the Tribal council of Great and Little Nicobar withdrew their support for the project, pointing out that during public stakeholder meetings they had not been informed by local government authorities that the land marked for development included their traditional pre-tsunami villages. In a letter to the environment ministry and Andaman & Nicobar administration, the Tribal council of Great and Little Nicobar said that they were not informed about the extent of “the Tribal Reserve that falls within the proposed project” and the precise “locations of the port and the township.”

“We are aware of how we are systematically being marginalized in this manner through this proposal and also the lack of understanding in the entire planning process that prevents our sustainable holistic development in both economy and through our island culture,” members of the council wrote. Their letter has yet to receive a response from the government.

This at-all-costs approach is symptomatic of the way the Modi government has been clearing infrastructure projects. An analysis by the Legal Initiative for Forest and Environment shows that in 2021 the NBWL approved all 129 proposals for diversion of land from wildlife sanctuaries, national parks, and conservation reserves for the purpose of mining, irrigation, roads, and highways. Headed by the prime minister, environment minister, and Tribal affairs minister, among others, the board granted approvals “without waiting to verify conservation plans, allowing projects without site inspections or the reviewing of necessary details like compensatory afforestation,” the study says.

Much of this is true for the Great Nicobar project as well. Backed by a hasty EIA report, institutions like the WII and Zoological Survey of India have been tasked with monitoring the project’s ecological impacts once construction is underway. The protected status of the Galathea Bay was rescinded in January 2021, nearly a year before the release of the draft EIA and before the government had clarity on the feasibility of building a port there. As the Legal Initiative study points out, India’s Wildlife (Protection) Act does not allow for the “denotification” of an entire wildlife sanctuary, as has been done in this case. The law only allows the alteration of boundaries of protected areas, thus raising more questions on the legality of constructing a port at Galathea Bay at the cost of widespread habitat destruction of some of the world’s most vulnerable and endangered species.

“Animals can usually recover from population declines if they have the opportunity to reproduce and there are resources for the offspring,” says Sanker. “But what is harder to recover from is the loss of habitat.” As things stand, the threat of habitat loss looms large over the thousands of species that call Great Nicobar their home.

As Sekhsaria puts it, the best mitigation plan for them “is to not have the project at all.”

Previously in The Revelator:

Six Lessons From the World’s Deadliest Environmental Disaster