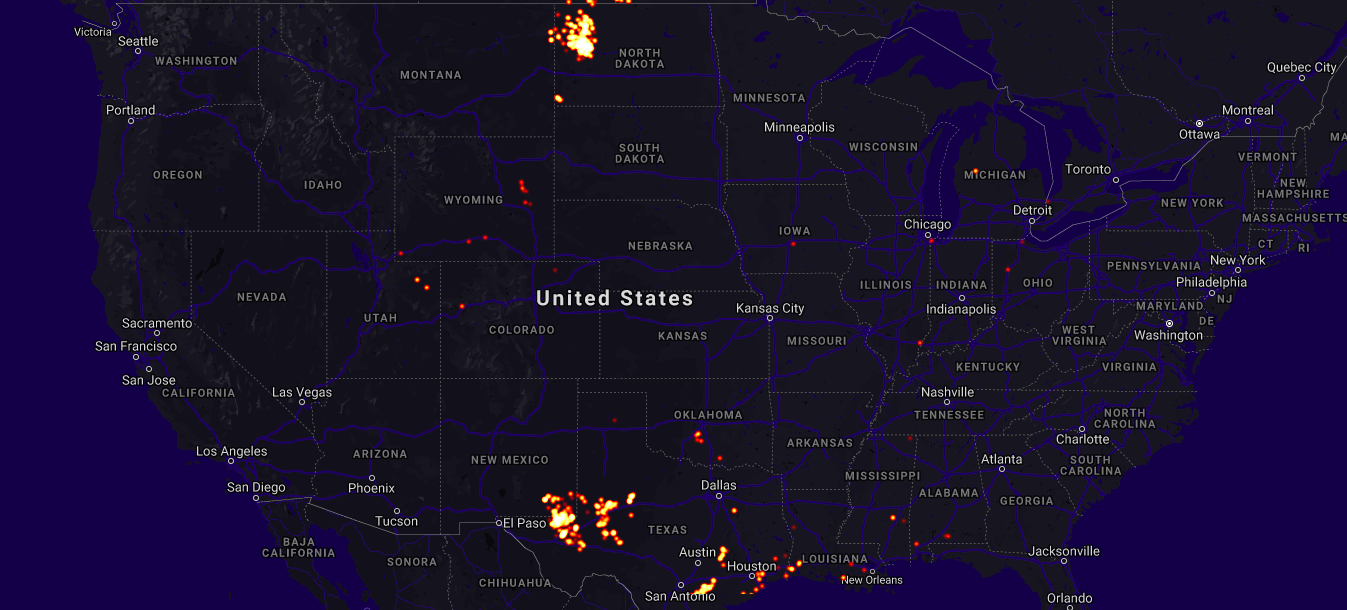

A night time satellite image of the United States shows a few concentrations of glowing lights, but not in the places you’d expect. The brightest spots aren’t the big cities but are instead clustered over North Dakota, west Texas and eastern New Mexico.

That’s because this infrared photo, produced by the nonprofit SkyTruth, captures not the lights of urban centers but heat from oilfields burning, or flaring, natural gas in 40-foot-tall stacks.

It’s also capturing a big problem.

The United States is fourth in the world in the volume of gas flared, following only Russia, Iraq and Iran.

There are a number of reasons why drillers flare gas.

“The most benign reason for flaring is safety,” says Gunnar Schade, an associate professor in atmospheric sciences at Texas A&M. Flaring releases pressure so that highly combustible materials don’t explode as wells are being drilled and prepared for production. Sometimes gas is also vented, without combustion, directly into that atmosphere.

“But that’s actually the exception in the oil and gas field,” he says. “The bulk is routine flaring.”

And “routine flaring” isn’t done for safety; it’s done solely to save industry money. But it comes at a cost to public health and the environment instead.

It’s most commonly used in oilfields like North Dakota’s Bakken shale, the Eagle Ford shale in Texas and the Permian basin, which straddles Texas and New Mexico.

Companies in these fields are most interested in oil, but what comes to the surface is a mixture of hydrocarbons, including raw gas, which is largely methane. Some companies have opted to just burn off these gases in flares instead of spending money on capturing and transporting it to market or waiting until the infrastructure to accomplish that has been constructed.

“To drill an oil well with the intention of never acquiring pipeline capacity to get the gas that’s produced along with oil to market is just wrong,” says Thomas Singer, a senior policy advisor at Western Environmental Law Center. His research found that some companies in New Mexico have flared the same well for three or four years. One company, Ameredev, flared 78% of its gas.

Now, more than a decade after the routine flaring became a glaring problem, states are taking some steps to reduce the practice. And the news coincides with research that finds the practice is more widespread, and dangerous, than previously understood.

Passing the Buck

The most obvious problem with flaring is that it’s simply wasteful. The value of flared gas in Texas’ portion of the Permian in 2018 was estimated at $750 million, according to research by the Institute for Energy Economics & Financial Analysis. The state could supply its residents with all of their gas needs with what is burned off as “waste” each year, the Institute found.

But in the process of burning off the gas, flares also release smog-forming nitrogen oxides (NOx) and carbon dioxide — a greenhouse gas we need less of, not more.

“Although a single flare may be a relatively small source, the large number of flares and high variability of NOx production per flare can cause large-scale atmospheric impacts visible from space,” Schade wrote in an essay about his research in The Conversation.

Flares, especially when they’re aren’t burning properly, can also release a host of other harmful emissions, including volatile organic compounds such as cancer-causing benzene, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide and black carbon.

And when flares are partially or totally unlit, they also vent methane — a greenhouse gas 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide in the short term. In North Dakota researchers found that incomplete combustion of flares were responsible for nearly 20% of the methane emissions in the Bakken shale.

Partially lit or unlit flares aren’t an anomaly.

Helicopter surveys measuring methane emissions in the Permian basin found that about 11% were malfunctioning, with 4% being totally unlit and venting methane. The research was conducted by the Environmental Defense Fund and others.

This doesn’t make it into official numbers. When the EPA calculates the sources of air pollution, it uses previous studies to support an assumption that “properly operated flares achieve at least 98% destruction efficiency,” with 2% or less of the raw gas getting into the atmosphere uncombusted or partially burned. But this new research showed that emissions were likely 3.5 times higher than what would be calculated using the EPA’s methodology.

“What we found, based on our surveys, is that the efficiency — and this is conservative estimate — is probably closer to 93% based on the number of malfunctioning flares,” says Colin Leyden, the director of regulatory and legislative affairs at the Environmental Defense Fund.

These flares — whether fully burning, partially lit or unlit — “are just a massive source of climate pollution,” says Singer.

Flares don’t make great neighbors, either. Those who live nearby are subject to the roaring noise of the fire, light pollution and other harm from the emissions.

A 2019 study published in Environmental Science and Technology looking at flaring in the Eagle Ford shale in Texas found that between 2012 to 2016 a whopping 43,887 flares emitted an estimated 4.5 billion cubic meters of gas. And those flares were highly concentrated.

“Of the 49 counties in the region, 5 accounted for 71% of the total flaring,” the researchers wrote. “Our results suggest flaring may be a significant environmental exposure in parts of this region.”

Flares in the Eagle Ford emitted more than 15,000 tons of volatile organic compounds and other contaminants in 2012 — more than the pollution from six of the region’s oil refineries, an investigation by the San Antonio Express-News found.

The health implications may also be generational. Pregnant women living within three miles of frequent flaring had about 50% greater chance of giving birth prematurely, a study published last month in Environmental Health Perspectives found. Preterm birth ratchets up the chances of a baby developing chronic health problems or even dying.

“The fact that much of the region is low income and approximately 50% of residents living within 5km of an oil or gas well are people of color, raises environmental justice concerns about the potential health impacts of the oil and gas boom in south Texas,” the researchers concluded.

Understanding the Problem

The problem is a big one and much worse than officially reported, new research suggests.

Work by Schade and colleagues reviewing satellite images of Texas oilfields found that from 2012 to 2015 volumes of gas flared were double the amount that companies reported to the state. Other research has found discrepancies in North Dakota and New Mexico, too.

So it’s not surprising that a 2020 study in Science Advances found record high levels of methane emissions in the Permian that were double those found in previous studies at 11 other major oil and gas fields. The wasted emissions were enough to supply gas power to 2 million homes.

“The high methane leakage rate is likely contributed by extensive venting and flaring, resulting from insufficient infrastructure to process and transport natural gas,” researchers found.

In many of these booming oilfields drilling outpaces infrastructure — and regulators don’t seem to mind much. Or at least they didn’t. But growing backlash against routine flaring is forcing some states to take a harder look.

New Rules and Potential Solutions

During the Obama administration the Bureau of Land Management took a stab at trying to reduce methane emissions from oilfield operations on federal and tribal lands, including those from routine flaring.

The Methane Waste and Prevention Rule was enacted in 2016, but the Trump administration moved to roll back parts of the rule in 2018. A federal judge struck down that rollback in July. But it likely won’t be the end of legal challenges.

For oilfields not on federal or tribal lands, though, regulatory authority falls to the states.

“New Mexico has gone to great lengths to pass the Energy Transition Act and move its electric power sector from coal to renewables,” says Singer. Now the state has turned its focus toward reducing climate pollution from oil and gas operations.

Last month the state released two new draft rules for curbing emissions from oil and gas operations, including methane from flaring that would require companies to capture 98% of their gas by 2026 — one of the most aggressive proposed regulations in the country to date. The rules will need public comment and agency revision, but Singer is hopeful that the process could be completed this year or early 2021.

The proposed rule, he says, is a good improvement, but it could be stronger.

“We want the agency to just flat out, say, ‘if you don’t have a contract for a pipeline to get your gas processed, you just can’t drill,’” he says.

Of course, a rule is only as good as its enforcement.

“There needs to be a lot more transparency and accountability provisions so that the public knows how well the state’s doing and can let the state hear about it if they’re not enforcing the rule strongly,” says Singer. “We’re also pushing hard for third-party verification or auditing of company reporting.”

Texas has seen movement on the issue, too, but not nearly as extensive as New Mexico’s effort. This month the Texas Railroad Commission, the agency that regulates oil and gas operations, issued a proposed change to a form used by industry to request permission to flare or vent gas. Under the proposed changes, companies would need to more thoroughly explain why they need to flare and provide better data to assess their compliance.

This could cut down on the amount of routine flaring. But Leyden wants to see more. He says the Environmental Defense Fund is calling on Texas to end routine flaring in the Permian basin by 2025. Some companies are on board, and so are investors, he says.

“What’s really needed is leadership on the regulatory front to bring the rest of the industry along,” he adds.

But could reducing flaring end up just meaning more pipeline construction? That, too, would come with a steep environmental cost. Instead, Leyden says, companies can plan to build better facilities with centralized collection storage.

“If natural gas has any role in the future — whatever your opinion on that may or may not be — it’s going to have to get to a zero or near-zero emission profile in its upstream production,” he says. “And right now what we’re seeing in the Permian basin in methane emissions, as well as from flaring, is they have a long, long way to go for that.”

Singer says advocating for no drilling without adequate infrastructure isn’t a prompt to build more pipelines.

“Saying you can’t drill if you don’t know how your gas is getting to market isn’t saying to build a lot of pipelines,” he says. His organization hopes to see a transition to clean energy — and having more investment in networks of pipelines and processing facilities doesn’t align with that either.

Gas flaring and pipeline building, he says, are “both fights that need to be waged.”

![]()