“CalSTRS is using our teachers’ money to invest in the destruction of our own future,” says teen climate activist Dulce Arias.

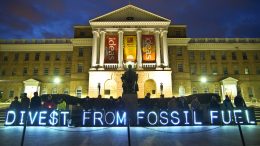

She’s talking about the California State Teachers’ Retirement System, which has billions of dollars invested in fossil fuel operations. Last year Arias and fellow activists in the Bay Area climate justice organization Youth Vs. Apocalypse launched a campaign to divest fossil fuel investments from the program. They have marched in the streets waving signs, sometimes dousing themselves in mock oil to call attention to the stakes. They’ve confronted decision-makers and politicians and more recently taken the fight online during COVID-19 quarantines.

The 19-year-old is part of a global movement fighting climate-divestment battles to essentially “defund” industries driving climate change by hitting companies where it hurts — on the stock markets and in access to loans and other financing. A report published last December by 350.org and DivestInvest called these global divestment efforts “the fastest growing social movement in history,” which has helped steer a growing sum of money away from fossil fuel investments — from $52 billion in 2014 to more than $11 trillion last year.

These passionate people-powered divestment campaigns even helped set the stage for Big Oil’s 2020 reversal of fortunes, according to financial analysts.

Despite all this, fossil fuel companies continue to wield enormous power and political influence — remaining a formidable, if weakening, opponent.

Climate scientists, meanwhile, warn that we must act now to head off the worst impacts of climate change.

“We are out of time,” says climate scientist and author Peter Kalmus. “The planet is screaming loudly…and it’s going to scream louder and louder the more we emit. More people are going to suffer and die and more ecosystems are going to be lost. The more fossil fuels we produce, the worse our lives today and the planet we leave for future generations will become.”

Business as Usual

Despite dire scientific warnings, fossil fuel financing continues full steam ahead.

A slew of expert reports say that most commercial banks remain resistant to adopting more stringent underwriting standards, which would enable further divestment. Even high-profile viral video campaigns like Jane Fonda cutting up bank cards have failed to shame big banks into making a change, and much of the banking and financial sector continues to resist “greening” their businesses.

“Move Chase’s money out of coal, oil, and gas now. If you don’t, we’ll leave your bank.” — @JaneFonda @Chase, we’re building an army to take on fossil fuel finance and #StopTheMoneyPipeline.

Take action here: https://t.co/dXjqCGvSJM https://t.co/MnDcMGmqfQ

— Fire Drill Fridays (@FireDrillFriday) January 22, 2020

Commercial banks have talked about greening their portfolios for decades, but critics say most have done little more than discuss risk “metrics” for analyzing portfolios, while limiting concrete changes to easier “sustainability” efforts like renovating their branches and corporate offices.

“There is no way through the climate crisis without addressing the financing behind the climate crisis,” says Jeff Conant, senior international forest program director with Friends of the Earth, part of Stop The Money Pipeline, a coalition of environmental and human rights organizations putting pressure on the financial sector. “It’s very hard to be optimistic.”

Indeed the numbers don’t look promising. A report published in March found that 35 global banks had provided $2.7 trillion in financing to fossil fuel companies since the United Nations’ Paris climate agreement was adopted in 2016.

Global deforestation, the second most significant climate change driver after fossil fuels, remains another area where lending practices are going in the wrong direction, Conant says. Another $154 billion in lending and capital have flowed to the top 300 companies known to be involved in global deforestation since the Paris accord was signed, he says.

“It’s clear that the finance sector is doing exactly the opposite of what it needs to do in terms of drawing down financing for these destructive industries,” says Conant.

As a result Stop The Money Pipeline has ratcheted up the pressure on banks, insurance companies, university endowments, pension funds like CalSTRS and companies like BlackRock, the world’s largest assets manager.

In response to climate activism, BlackRock chairman and CEO Larry Fink stunned the world of finance in January when he pledged to consider climate change impacts in the company’s investment decisions. “[W]e will be increasingly disposed to vote against management and board directors when companies are not making sufficient progress on sustainability-related disclosures and the business practices and plans underlying them,” Fink wrote in his annual letter to corporate executives.

Environmentalists, however, say BlackRock has yet to act on those intentions.

BlackRock has made “great strides in the last few years thanks to pressure from activists and the public, but in terms of coming up with an approach that actually makes a difference with the [climate] crisis, there’s a really long way to go,” says Conant. “For people in the finance industry, it was something that was unthinkable just a few years ago. So in that sense, it’s tremendous. But we have yet to see any of those words be put into action.”

Mounting Victories

There are reasons to believe that we’re nearing a tipping point, though.

In a webinar earlier this month, energy strategist Kingsmill Bond of Carbon Tracker, a London-based think tank focused on the impact of climate change on financial markets, urged listeners to be skeptical of “rather naïve” oil company forecasts that demand for their products will go back to business as usual.

“That’s just not going to happen,” he said, explaining that the COVID crisis has complicated matters for the whole fossil fuel sector at the same time the industry is going through structural changes. As a result, the pandemic will bring forward the date of peak demand for fossil fuels and hasten the transition to fossil-free energy powering our homes, offices and cars.

Financial analysts have no doubt that the divestment campaigns are contributing to Big Oil’s historic decline this year, as a COVID-induced recession led to an oil glut that sent crude prices plummeting below zero for the first time ever this spring.

Perhaps the most cautionary tale comes from Exxon Mobil Corporation, which saw itself delisted from the Dow Jones Industrial Average in August, a few weeks after the company reported a second straight quarterly loss and its stock price cratered. It was a spectacular tumble for a company that was ranked as the country’s most valuable as recently as 2011. The depth of the industry’s troubles developed surprisingly fast this year, exposing, analysts say, the extent to which the clean energy transition is increasingly inevitable.

“It’s very clear to us that COVID-19 will speed up the energy transition, in spite of the best attempts by the fossil fuel lobbyists to roll back the regulatory pressures,” said Bond.

What activists have achieved to date is no small feat. In California divestment advocates have already notched some significant victories. Last year, for instance, California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed an executive order calling on CalSTRS and other state pension plans to shift their portfolios to drive investment in climate resilience and carbon-neutral technologies.

Whether CalSTRS actually divests is still to be seen, but the momentum in California and globally appears to be building behind the activists. Of course, daunting obstacles remain — even more so in these COVID times when in-person activism is limited.

“On social media, when we put out something regarding the climate or anything related to climate justice, most of the time it’s only our own followers who see this content,” says Arias.

Nevertheless, she says she’s undeterred. She finds inspiration in the work of her fellow youth climate activists, as well as other movements for racial and social justice and immigrant rights.

This intersection of social and environmental movements, she says, will be key to tackling the climate crisis, along with other social and economic problems that COVID-19 has only exposed and exacerbated.

“Once we all unite, band together and show up for one another,” she says, “that is when we will have real change.”

![]()