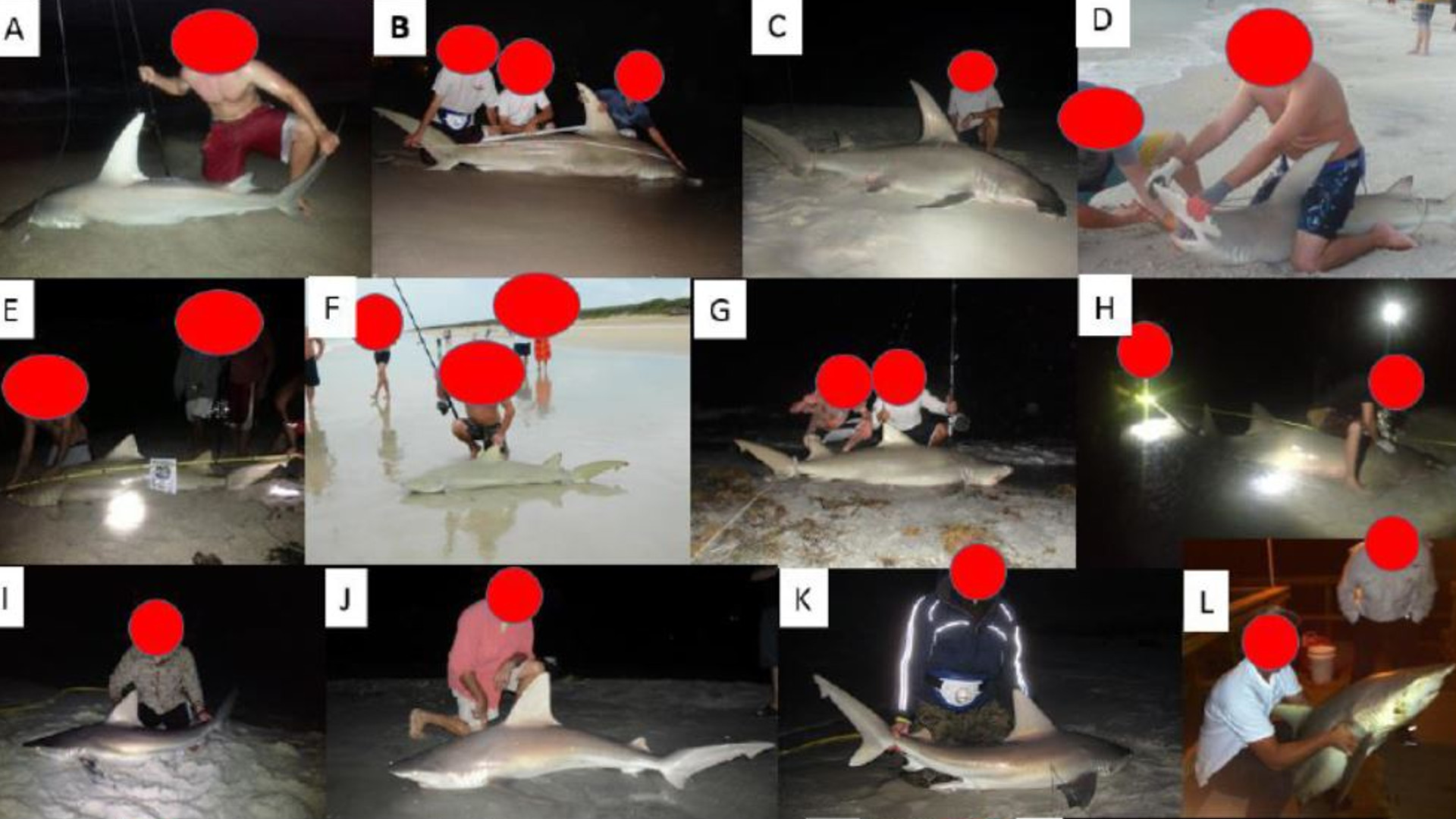

Florida is known for beautiful beaches and amazing fishing, but these two things don’t always mix. Photos showing anglers roughly, cruelly, disrespectfully and improperly handling threatened sharks on beaches and piers have recently gone viral on social media. Anglers drag sharks completely out of the water, where they can’t breathe and suffer bleeding abrasions from the rough terrain. They’re left to flop around until they are near death, making them calm enough that anglers feel comfortable approaching them to pose for photos. Dead sharks often wash up on the beach the next day — something that anglers may never see.

Recreational fishing is increasingly recognized as a conservation threat, and indeed more large sharks in the United States are killed by recreational anglers than by commercial fisheries. The problem is especially acute for species such as hammerhead sharks in Florida, whose populations have declined so much that they are protected entirely from commercial fishing in state waters. While most Florida anglers follow the rules and are conservation-minded, some common land-based shark-fishing practices like those described above raise concerns and require a policy solution.

As a marine conservation biologist who studied this problem while I was earning my Ph.D. at the University of Miami, I was thrilled to see that the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, at their meeting this past April, finally decided to take action and develop proposals to solve this problem.

But what should those solutions look like? To be as effective as possible at protecting threatened species without significantly infringing on the rights of rule-following anglers, here are some changes to land-based shark fishing regulations that the commission should implement — some of which anglers could begin to implement today in order to protect the sharks that they purport to love.

1. Revise and clarify the legal definitions of “landed” and “released” under the Florida code.

Currently a fish is considered landed if it is brought completely out of the water, which is illegal for protected species (they must be released “free, immediately, alive, and unharmed,” and it’s illegal to delay release of a protected species to measure it or pose for a photo). However, irreparable gill damage can occur in many species after just a few minutes of air exposure. Therefore, protected species need to be left in deep enough water that their gills remain submerged.

2. Limit fight times for hammerhead sharks.

Hammerhead sharks are valued by anglers for their energetic fights, but stress physiology research has shown that after about 40 minutes of fight time, a hammerhead is likely so stressed that it won’t survive release. Land-based anglers commonly fight hammerheads for much, much longer than that, resulting in dead hammerheads washing up on Florida beaches. Anglers should be required to cut the line as quickly as possibly as close as possible to the shark, and definitely cut the line once a particularly length of time has elapsed. While dragging a long length of fishing line behind it is not great for a hammerhead shark, fighting an angler for several extra hours so the hook can be removed completely is much worse.

3. Remove categories for protected species from Florida fishing tournaments.

It’s illegal to delay the release of a protected species to measure it or pose for a photo, but many Florida fishing tournaments have award categories for protected shark species — and in order to be eligible for an award, anglers must measure their catch and/or pose for a photo. There should be no tournament categories allowed for protected species.

4. Require specific gear.

Certain types of higher-performance fishing rods can result in lessened fight times, which reduce stress for the shark. Circle hooks reduce the chance of foul-hooking or gut-hooking. These should be required for fishing for large sharks.

5. Create a shark-fishing license.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has proposed creating a specific shark-fishing license that would allow them to more easily track the scale of the recreational shark fishery. While I support that goal, it’s important for the commission to stress that having this license does not mean that anglers are free to ignore other regulations.

These changes to regulations would protect threatened sharks, and they’d do so without infringing on anyone’s rights to fish responsibly. They are endorsed by professional organizations including the American Elasmobranch Society and the Society for Conservation Biology (North America section and Marine section).

I’m no anti-fishing extremist — indeed, my postdoctoral research focuses on sustainable shark fisheries management in North America. However, I am against the needless stress placed on protected shark species by unnecessary and cruel fishing practices used by some elements of Florida’s land-based fishing community.

I call on the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission to do the right thing and implement these policy changes.

Copies of Dr. Shiffman’s research paper on land-based shark fishing are available upon request at [email protected].

© 2018 David Shiffman. All rights reserved.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.