It’s not even February yet, and Florida panthers are already having a bad year. Three have been killed by vehicles and one by a train in the first two weeks of 2020 alone.

The big cats once ranged across the South but now are mostly found slinking between fragments of habitat in southern Florida. Traffic poses a significant hazard: Last year 23 panthers were killed by vehicles — a significant blow to a wild population that hovers precariously at only around 230 animals.

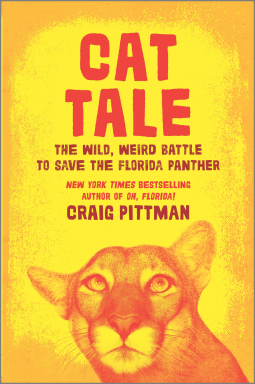

But there likely wouldn’t be any Florida panthers today if it weren’t for decades of work to save them. The story of how Florida panthers, a puma subspecies, were rescued from the brink of extinction is expertly told in the new book Cat Tale: The Wild, Weird Battle To Save the Florida Panther, by journalist and New York Times best-selling author Craig Pittman. Pittman’s been tracking the story for 20 years at the Tampa Bay Times.

The cast of characters and wild turns of event in Pittman’s book seem like the stuff of fiction. There’s the Stetson-wearing Texas cougar hunter Roy McBride, who becomes a master panther tracker. Veterinarian Melody Roelke rings the alarm on the panther’s genetic problems, only to have her male colleagues look the other way. And the arch villain of the story, a biologist nicknamed “Dr. Panther,” establishes himself as the preeminent expert but is actually fudging his research and colluding with developers.

Pittman traces these and other characters through years of discoveries, mistakes, public backlash and breakthroughs — a fledgling program to radio-collar and track the animals that taught important lessons about tranquilizing big cats high up in trees; a failed captive-breeding program; a failed reintroduction plan in north Florida; and a last-ditch effort to bring in new genes by releasing Texas cougars in panther habitat.

The story is tragic, inspiring and deeply poignant. In his prologue Pittman calls it a “scientific cautionary tale.” As we grapple with mass extinction across the world, he writes, “This is a guide to what extraordinary efforts it takes to bring back just one sub-species — one that’s particularly popular — and what unexpected costs such a decision brings.”

Pittman talked to The Revelator about the threats that panthers continue to face and what lessons we can learn about saving other endangered species.

When you first started writing about panthers 20 years ago, what did you think about their prospects?

My first stories were around 1998-1999. Nobody knew if the Texas cougar experiment had worked yet. Things looked pretty grim and a lot of developers were proceeding on the understanding that panthers wouldn’t be a problem anymore, so it was OK to build in panther habitat.

Things looked dire at that point and it wasn’t until around 2001 or 2002 where you started seeing these new kittens being born and thinking maybe things would be OK. The concern then became making sure that the Texas cougar genetics didn’t swamp the panther genetics.

We know that panthers aren’t out of the woods yet. Is there clear science on what would be considered a recovered population?

Ever since scientists drew up the very first recovery plan decades ago, they said the key was to have three [geographically] separate populations of about 250 or 300 panthers. Obviously, we’re still a long way from that and from even starting a second population. You could call what’s going on in central Florida the start of a new population, but there’s just a handful of panthers there. If they choose to follow those particular goals, they’re a long way away.

But I phrase it that way because [the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service] did not follow their own recommendations when they down-listed manatees [from endangered to threatened]. They didn’t follow their recovery plan. They just said, “Well, this computer model says it’s OK, so we’re going to say it’s OK, even though the threats are still there.”

You know a good bit about manatees, which you wrote about in Manatee Insanity: Inside the War Over Florida’s Most Famous Endangered Species. How does the manatee’s story compare to the panther’s?

I call manatees “the endangered species you can see,” because they will show up everywhere people are — they’re in your backyard canal, swimming around your dock. At the time I wrote that book, they were an endangered species, but one that you could see with your own eyes.

Panthers, not so much. Panthers are very elusive. They don’t like to be around people. So they’re more of an abstract concept to a lot of folks. People know the panthers exist, but they’ve never seen one. So it’s not quite as personal with panthers.

And the other thing that I wrote about in Manatee Insanity is that the Save the Manatee Club, and specifically its cofounder Jimmy Buffett, came up with this brilliant marketing concept called “adopt a manatee,” where they took the IDs from a whole bunch of the manatees that the state had been following and, for a contribution of around $5 or so originally, you could adopt a manatee. You’d get a little adoption certificate with the name of your manatee on it and its background.

People became personally invested in the fate of their particular manatee. I was digging through state archives and I saw letters from, you know, Mrs. Johnson’s fourth grade class in Mesa, Arizona to the Citrus County Commission saying, “Why are you being mean to our manatee and not passing this rule to make boats slow down?”

They found a way to make people all over the country care about individual manatees as a way of getting them to care about the species as a whole. There’s no similar project for panthers and generally most of the panthers don’t have nicknames like the manatees do.

There are people who absolutely love panthers, mostly in the abstract. And there are some folks who would dearly love to see a hunting season opened on them and feel like the government’s lying about how many there are. But I think the majority of Floridians support panthers and are happy that they seem to be coming back.

Your book is a really incredibly in-depth case study of what it takes to save one endangered species. Are there lessons we can learn from it about saving other species?

I like what Melody Roelke said — at the point where they started to realize they needed to take action [to save the panthers], it was almost too late to do anything. So her advice was, if you see it heading this way, take action immediately. Don’t dawdle around and get into arguments and get mired down in bureaucratic red tape about what you’re going to do.

They really were almost too late to save the panther. It basically came down to five female Texas cougars breeding with the remaining male panthers. And had that not worked, that would’ve been it. They’d probably be gone by now.

The other thing is, if you’re going to spend this much money and work this hard to bring back an endangered species, think about what’s going to happen afterwards. What are the ramifications going to be? Because as we saw with the captive-breeding experiment that they started and then dropped, they had not planned very well. They had figured out they were going to take these panther kittens out of the wild and breed them in captivity to put [grown] panthers back in the wild, but they hadn’t really thought about where they were going to put them and how they were going to train these captive panthers to be OK in the wild.

What are the biggest threats they face now?

The reason I waited so long to write this book is because I needed a good ending and I finally got one. [Editor’s note: We won’t give it away, but it’s a doozy.]

But just because I found an ending for the book doesn’t mean the story of the panther is over. We’re now dealing with this mystery ailment that’s afflicting some panthers and bobcats, to the point where they can’t walk and scientists don’t know why.

We’ve also got more large development coming down the pike headed for the area [where most panthers live]. In particular there’s a proposal backed by the governor — who is supposedly pro-environment — to build this enormous toll road right through panther habitat, which would bring more development into that area.

One of my colleagues, Lawrence Mower, just wrote a story where we’d gotten copies of some emails from Fish and Wildlife Service biologists who study the panthers saying this will just basically be a stake in the heart of panther recovery if you build this toll road through there.

So there are continuing threats, and we’re a long way from them being considered recovered. But things are looking hopeful in ways they haven’t for a long time and all because of the very hard work from these folks who labored for years mostly in anonymity because they believed in the cause and they believed that what was going on was something worth devoting their lives to — even though it led to burnout and fighting and depression and, in one case, suicide.

In a way, I wrote the book to call attention to the role of those unsung heroes to say, look at what they did, look at the risks that they took, look at the brutal work days they put in trying to figure this out — sometimes even against the public’s own desires.

![]()

1 thought on “The Crazy Story of How Florida Panthers Were Saved From Extinction”

Comments are closed.