Tiger Shark Terror. Great White Shark Serial Killer Lives. Great Hammerhead Invasion. Australia’s Deadliest Shark Attacks. These are just a few of the programs airing this week during Discovery Channel’s annual Shark Week and NatGeo Wild’s copycat, Sharkfest. Undoubtedly these programs will attract their usual massive ratings, but they may be guilty of the same kinds of film fakery that plagues many wildlife films, where the images on your screen don’t tell a full or even truthful story. In the process, experts warn the films may actually send the wrong conservation message and harm endangered species.

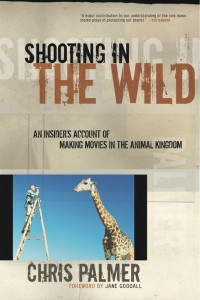

“The term ‘fakery’ has many nuances to it,” says Chris Palmer, founder of the Center for Environmental Filmmaking at American University in Washington, D.C. Palmer shined a light on some of the worst aspects of wildlife filmmaking in his 2010 book and 2013 documentary Shooting in the Wild. Shark Week, he says, typifies one of the most common aspects of film fakery, where producers create a mistaken impression in the audience’s minds about what goes on in the wild. “With Shark Week, people get to see sharks as being dangerous and man-eating because that’s what gets ratings. The networks are looking for that male demographic, age 21 to 35, so they push sensational shots of sharks chomping down on people.”

“The term ‘fakery’ has many nuances to it,” says Chris Palmer, founder of the Center for Environmental Filmmaking at American University in Washington, D.C. Palmer shined a light on some of the worst aspects of wildlife filmmaking in his 2010 book and 2013 documentary Shooting in the Wild. Shark Week, he says, typifies one of the most common aspects of film fakery, where producers create a mistaken impression in the audience’s minds about what goes on in the wild. “With Shark Week, people get to see sharks as being dangerous and man-eating because that’s what gets ratings. The networks are looking for that male demographic, age 21 to 35, so they push sensational shots of sharks chomping down on people.”

Palmer, who has won two Emmy Awards for his own wildlife films, believes that pushing this misinformation — that sharks are nothing but dangerous killing machines — can hurt conservation efforts. “The wrong perception can lead to misperceptions and in the end, I think, hurt public policy toward these animals,” he observes. “One has to wonder how that affects work that goes on at CITES [the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species] and places like that where we try to get international protection for sharks. If the populace is thinking of sharks as dangerous, why would anyone save them? That makes it harder, I think, to do the right thing.”

Real or fake?

Demonizing animals is just one of the many kinds of fakery tainting the wildlife filmmaking industry. Another kind of deception involves manipulating events to get the “right” shots on film. That might include leaving food out for animals, dosing a carcass with candy, drugging animals so they don’t move or pushing them toward the camera. “The worst case is when you put predator and prey together to get photographs,” Palmer says. Although this technique has been employed extensively in the past, he calls it immoral: “You get these dramatic shots, but people don’t see animals as they really are.”

In other cases, what appears to be on camera isn’t completely true even if it may seem to be that way on the surface. Some films claim to follow the story of specific animals, although the footage is of multiple individuals edited together to tell a “real” story. In other films, discordant shots are edited together to depict something that could not be filmed in the wild. Sir David Attenborough’s Frozen Planet series infamously mixed footage of polar bears in the wild with sequences shot in a zoo. This created a scandal a few years ago when viewers found out, and the Discovery Channel added a disclaimer when it brought the series to the U.S.

A more subtle kind of fakery can occur in the editing stages. Filmmakers might be in the field for months at a time, getting limited shots of their subjects every few weeks. But all too often those short shots can be edited together to make it seem as if they occurred in a very short sequence. “The final film looks like there are a lot of these rare animals,” Palmer says. “People watching it are saying to themselves, ‘Well, golly, what’s the problem? I was just watching this film, and I see hundreds of these chimps or these white-tipped oceanic sharks or whatever,’ and then they don’t realize that the film has been put together with very little footage because it’s hard to find these animals.”

The risk to wildlife

In addition to fakery, Palmer points out that the animals themselves are often endangered by filmmakers. “We get too close, we harass them, we’re desperate to get the money shots,” he says. “And we go in so close and bother them that some of the animals even get killed.” Ethical codes for filmmakers should prevent this from happening, but they lack enforcement. “They set a marker, but if someone breaks them there is no one in the field to say, ‘Don’t do that,’” Palmer says.

Many filmmakers may find themselves placed under extreme corporate pressure to get dramatic footage of rare and endangered species. Because most crews contain just one or two people and no one is in the field watching, circumstances can lead to cutting corners. “No one’s looking at you,” Palmer says. “It’s very easy to do things that no one would know about.” He notes that there aren’t any real metrics about this, because people don’t admit it, but it happens: “The only time you hear the truth is at 2 A.M. after a few beers.”

The public’s role

The public can have a role in reducing film fakery, whether it’s during Shark Week or on another wildlife program. “I would encourage people to be a little skeptical and ask questions,” he says. “How did they get that shot? Is the animal being controlled? Did that animal come from a game farm where it was held under inhumane conditions? Especially for endangered species, how was it treated? Did the filmmakers keep their distance so the animal was undisturbed or was the animal harassed and chased down to get good footage?” Asking television networks these questions, he suggests, can lead to change: “All of these networks are sensitive. I think if the public speaks up, they will do a better job.”

Although he expresses a lot of criticism for fakery, Palmer does think that wildlife filmmaking can have a very positive effect, even in cases where the narrative plays loose with a few facts to pull at heartstrings. “People who love the film may vote in a positive way for senators and congressmen who will vote in a more sustainable manner,” he asserts. “That may be an example where fakery is, if you like, pro-conservation.”

A version of this article appeared in 2013 at Scientific American.

The Discovery Channel is notorious for this. While I love watching wildlife films and videos, I’ve been turned off to them lately once this behavior was exposed. Much better to just hike, camp, and snorkel or sail to see wildlife for yourself (and keep your distance!).

The idea that wildlife only exists in order to provide “entertainment” for us – humans – seems to increase with every addition to social media these days & with every new “reality” show. The scarier & the more exciting, the better. Yeah, keeping our distance & seeing wildlife for real without interacting might be a lot more satisfying for us & certainly for the wildlife!