Americans are finally beginning to understand the severity of the climate crisis. Nearly three-quarters of Americans now say global warming is “personally important” to them, even as the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports that we have just 11 years to take dramatic action to avert climate catastrophe.

I guess we should see this as good news — better late than never — but a crucial question remains: Does America have the political will to enact the big changes needed to address climate change before it’s too late?

There’s a simple answer: Yes, but only if environmentalists vote.

The 2018 midterms were something of a high-water mark for turnout of environmental voters. More than 8 million “environment-first” voters flocked to the polls last November, a robust showing that has spawned renewed interest in a Green New Deal and carbon pricing — although not nearly enough interest to actually pass such measures.

Now, imagine how politicians would react to these kinds of initiatives if twice as many environmentalists turned up to vote.

It’s not an impossibility. In the 2016 presidential election, 10 million environmental voters stayed home in an election that was decided by fewer than 80,000 votes. Even if only half of them started voting, that would be a “green wave” impossible for any politician to ignore.

Simply put, politicians will always go where the votes are. If environmentalists aren’t voting, we’ll continue to be ignored. If we show up to vote, politicians will follow. If you’re not convinced, look at the host of Democratic presidential candidates now scrambling to appeal to the growing block of Democratic climate voters.

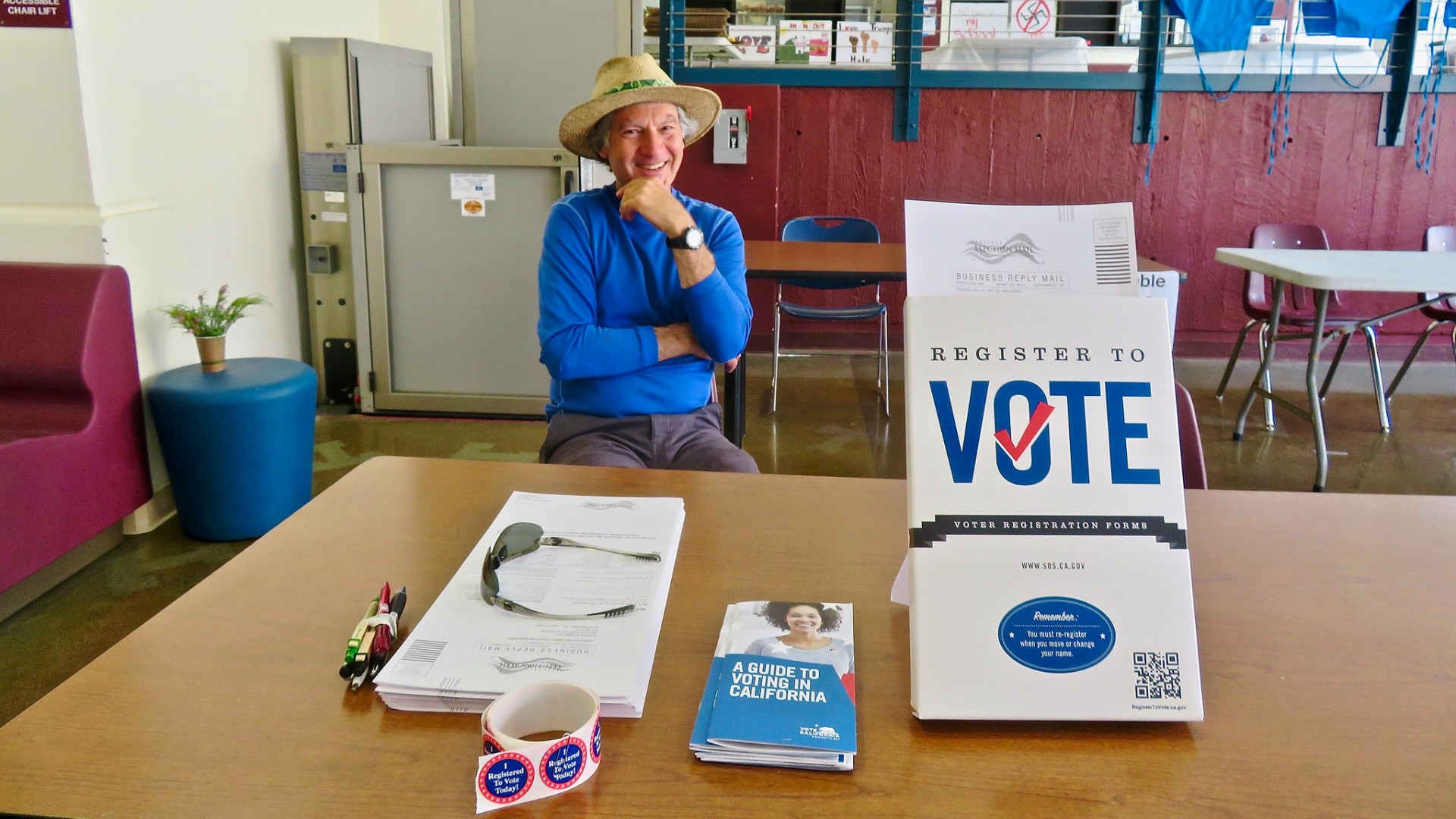

At the Environmental Voter Project, our goal is to turn these millions of non-voting environmentalists into an army of super-voters who drive policy-making at the local, state and federal levels.

And we’re already making progress.

In the 2018 midterms, the Environmental Voter Project targeted over 2.1 million unlikely-to-vote environmentalists in six states (Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Massachusetts, Nevada and Pennsylvania). Ultimately, our efforts resulted in 58,961 new environmental voters being added to the electorate.

How’d we do it? By treating people as social beings — not rational beings — plus a healthy dose of peer pressure. We don’t try to rationally convince people of the importance of voting; instead we appeal to how they wish to be viewed by their friends and neighbors. Using the latest behavioral science research, we tap into widely accepted societal norms: our desires to be good citizens, to fit in with our peer groups and to not be left behind. We often remind environmentalists that their voting records are public, and that most of their friends or neighbors voted in the recent election.

For instance, we mailed voters copies of their public voting histories and increased turnout by as much as 3.4 percentage points in some states. Our volunteer canvassers asked non-voters to sign pledges to vote, and then we mailed those pledges back before Election Day, increasing turnout by 4.5 percentage points. Our digital advertisements said things like “Be a good voter,” “Your neighbors are voting; are you?” and “Who you vote for is secret; whether you vote is public record.” These simple messages increased turnout 0.4–1.2 percentage points.

Some of our turnout techniques had different results with different demographic groups — direct mail did better with older voters and people of color, whereas text messages performed better with younger voters — but most interventions ended up increasing turnout well over 1 percent, which is a big deal in politics.

In short, these techniques work. We’re turning non-voters into voters.

The best part is that habits are sticky, which means that many of these new voters will keep showing up, and campaigns will start paying attention to them as regular voters. Just three years after launching, the Environmental Voter Project has already created 93,423 environmental “super-voters” — people who previously did not vote, yet now vote so consistently that politicians are fighting for their attention.

This is the kind of concerted, year-round mobilization effort the environmental movement needs. We must treat every election — no matter how small — as an opportunity to turn non-voters into voters. And in 2019, voting in your local city council, mayoral or statewide elections is particularly important — not just because of the impact on local and state policy-making — but also because it tells 2020 candidates which new voters they need to pay attention to.

To encourage these consistent voting habits, the Environmental Voter Project is treating 2019 as if it were 2018 or 2020. We’ve already worked with thousands of volunteers to mobilize environmental voters in over 60 elections since last November’s midterms — from municipal elections in Las Vegas, Jacksonville and Colorado Springs to state legislative races in Pennsylvania and county-wide ballot measures in Georgia. Before 2019 is over, we’re expecting to contact more than 2 million environmental voters in Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Massachusetts, Nevada and Pennsylvania, and we may expand into additional states beyond that.

Clearly, the momentum is shifting. We saw the beginning of a green wave in 2018, but we’re not yet a big enough voting block to bring about the enormous policy changes that we need. So we need to start showing up.

The United Nations says we have 11 years left to avert climate catastrophe. As environmentalists, it’s our duty to spend these next 11 years voting in every election and mobilizing other environmentalists to vote too. And we must start now.

Together, we can turn this growing green wave into the sea change we need to force politicians to act before it’s too late.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.

![]()