One of the world’s rarest, most beautiful and least-seen frogs has been rediscovered — thanks, in part, to a scientist’s parasitic infection.

Two years ago a team of scientists arrived in Ecuador’s Río Manduriacu Reserve, an astonishingly lush and biodiverse canyon that’s the only known habitat for the critically endangered Tandayapa Andes toad (Rhaebo olallai). The researchers had planned a series of night surveys in the hopes of documenting the breeding behavior for the rare toad, which had been rediscovered there in 2012.

But after the first few night surveys, one of the researchers — conservation biologist Scott Trageser, president of the Tucson-based Biodiversity Group — decided he needed to stay behind. He hadn’t been feeling well, he recounts, and was too fatigued to participate. Instead, he thought he’d look around a stream close to the team’s base camp, where the toads had previously been easy to observe.

He couldn’t find any toads, though. And despite his fatigue — which he later learned was caused by undiagnosed internal parasites that were “slowly ravaging my soul and body” — he continued his quest late into the evening, trekking over “some rather precarious waterfalls” in the process.

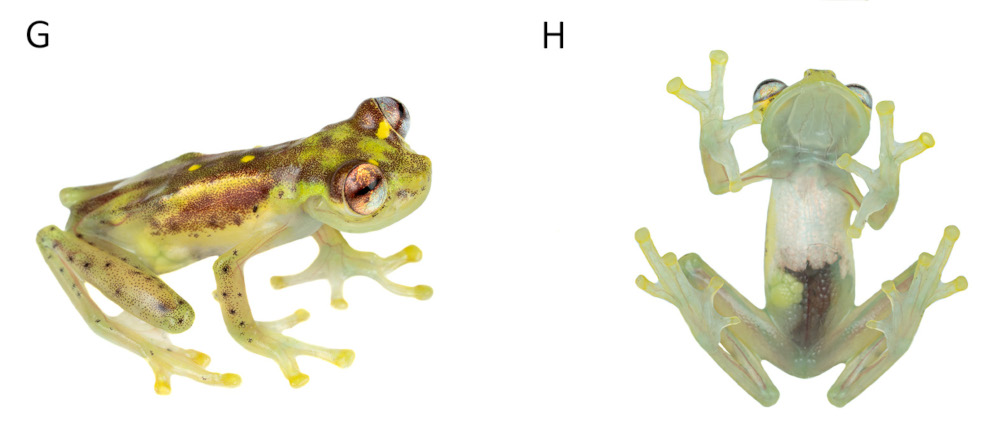

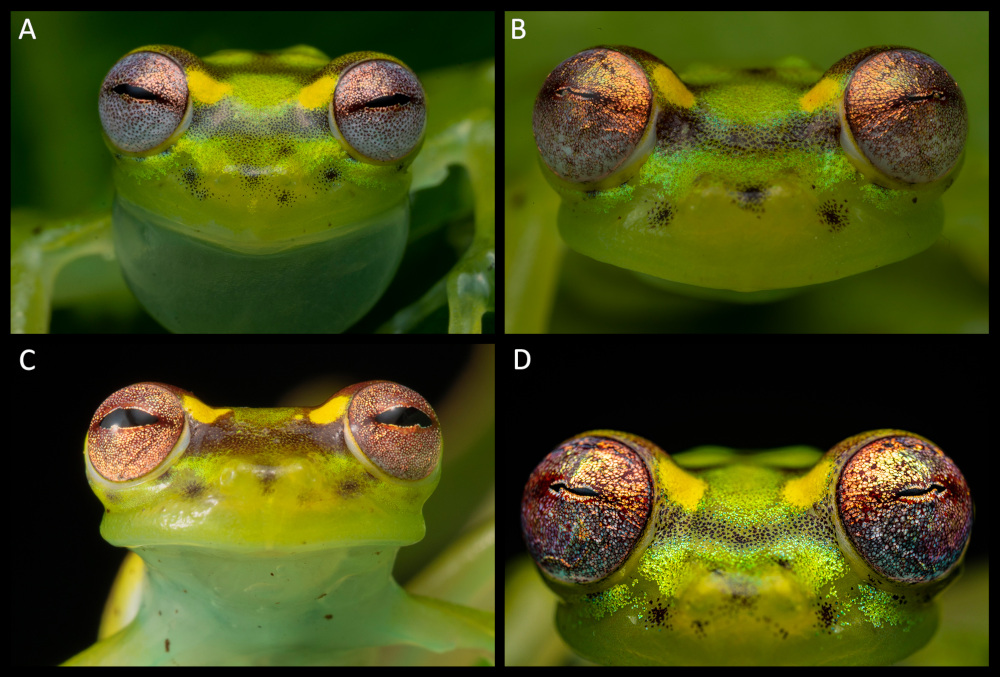

Soon an unexpected animal call reached his ears. He looked around and saw a tiny male frog of a species he didn’t recognize. It had yellow-green skin, bulging red eyes and a translucent abdomen. The calls continued: The frog was actively calling for mates.

Trageser carefully picked up the colorful, one-inch-long frog and placed him in a bag with some water and foliage, then continued looking for toads for almost the whole night.

He arrived back at base camp at 7 a.m., collapsed for four hours, then woke up and eagerly opened the bag and showed its contents to his colleagues.

And blew their minds.

They knew exactly what it was: a Mindo glassfrog (Nymphargus balionotus). The last time anyone had observed the species was 2005, when just a single male was found. Before that it had gone unseen since 1984.

They couldn’t believe their eyes.

“Upon opening the bag and realizing what species he had just found — it’s unmistakable, if you’re familiar with the few photos that existed at the time — our team exploded with excitement,” says biologist Ross Maynard, Ecuador program director for The Biodiversity Group. The team had already discovered another new-to-science species of glassfrog on the same expedition, so this made two amazing findings. (The team published its research on the other species, Nymphargus manduriacu, named after the reserve, last year.)

Three further surveys conducted in 2019 revealed more Mindo glassfrogs in three different streams within the reserve. The researchers observed several females — another scientific first, as all previous observations had been males. They also found metamorphs and two egg masses — proof that the frogs not only existed there but were actively breeding.

The researchers (including Trageser, who got over his infection) published the news of their rediscovery last month in the journal Amphibian & Reptile Conservation and say the species should be considered endangered.

And the entire reserve could use more protection.

A Hidden Eden

With less than four square miles of protected land under its wings, about 40% of which is owned by locals, the remote Río Manduriacu Reserve isn’t particularly large. But a heck of a lot of wildlife lives among its abundant vegetation, free-flowing creeks and cascading waterfalls.

“To highlight our findings on just the herpetofauna, the reserve can claim to harbor the only known extant populations of four frog species,” Maynard says. They’ve also now documented “two novel frog species that have been formally described, 24 total species listed by the IUCN as being threatened with extinction, and numerous records substantially expanding the known range of various species.”

The reserve also serves as important habitat for several previously unknown orchid, a variety of birds and numerous mammals, including six feline species and the critically endangered brown-headed spider monkey (Ateles fusciceps).

And that’s not all: Maynard reports that a team led by zoologist Jorge Brito has discovered a new mammal species on the reserve, which represents an entirely new genus. (That research is still working its way through the scientific publishing process.)

That’s not bad for a reserve that didn’t even exist until a few years ago.

“My family and I came across the property by chance,” says Sebastián Kohn, executive director of Fundación Cóndor Andino (the Andean Condor Foundation), which manages the reserve with the EcoMinga Foundation. “The previous owner of one of the plots is an old family friend. By chance we talked about the place and decided to take a look. At the time access to the properties was a lot harder — at least six to eight hours walking — so we didn’t even see them up close before purchasing. We knew they had good forest and immediately fell in love with the Manduriacu River. The price was so cheap that we decided we couldn’t pass on the opportunity to purchase and conserve the forest, even though we still had no idea of its conservation significance.”

That significance quickly became evident when Kohn and other researchers rediscovered the Tandayapa Andes toad there in 2012. The finding helped to inspire the formal push to turn the land into a reserve in 2017.

But the land and its rare residents still aren’t completely secure. Cattle pastures east and south of the reserve have encroached on the forest, and miners have tried to illegally access the property. Mining and deforestation have boomed in Ecuador in recent years, spurred by 2016 deregulation that opened 13% of the country to mining exploration and made it easier for foreign companies to acquire concessions. An open-pit copper or gold mine situated in the canyon could easily send detritus and mercury flowing downhill, where it would pollute the watershed and harm wildlife, as has happened in other parts of the country.

“Sadly, this would all but guarantee the extirpation of the local populations of threatened species documented at the reserve,” says Maynard.

Luckily the local community of 200-300 people, living a couple of miles south of the reserve, opposes mining, in no small part because the researchers and EcoMinga Foundation have spent so much time developing personal relationships and financial-empowerment initiatives. As the researchers report in their paper: “During an attempt by the mining company to access [the reserve] in August 2019, community members came together to assert their position that mining personnel will no longer be able to bypass the necessary lines of communication and documentation to access either the reserve or their private property.”

International forces could also come into play. The mining company that illegally entered the reserve is a subsidiary of BHP Billiton, which has a local alliance with Conservation International and is part of the United Nations Environment Programme’s PROTEUS program, which supports the international development of biodiversity information. “Both partnerships demand that BHP has to protect endangered species and their habitats,” Maynard points out. “Therefore, in our view, if either of these relationships are to maintain credibility in light of the data we are reporting, BHP must abandon their interests within the canyon.”

The Protection of People

In addition to standing up against corporate interests, the researchers and community members have also developed a mutual appreciation for local wildlife.

“Much of the community is nearly as excited about the biodiversity of the reserve as we are, especially the kids,” Maynard says. The conservationists have even provided interested residents with cameras to document the wildlife they encounter. “There are already around a dozen amphibian and reptile species that we’re aware of in the canyon strictly from either community members or EcoMinga staff sending us photos — a perfect example of how science benefits from engaging and including the help of locals.”

Resisting the lure of mining jobs will probably remain an issue in a place that doesn’t have many other options for income. That’s why the foundations continue working to develop alternatives to the people around the reserve. “In the end, they want what most people want: to earn a living for their families and to appreciate the land around them,” he says. “The solution to protecting the reserve is by finding sustainable jobs for community members that serve as alternatives to destructive practices such as mining or cattle ranching.”

As part of that effort, Maynard says, EcoMinga has hired an aspiring naturalist from the community, Jimmy Alvarez, as part of its staff. “These are the types of actions that I believe will lead to long-term conservation success: training and hiring locals to be part of the solution while earning a salary.”

Work Still to Be Done (After the Pandemic)

The research team still has a few more publications and species assessments pending from their previous expeditions, and they’re getting ready for more — eventually.

“Once the pandemic has been tempered, we absolutely look forward to continuing our efforts at the reserve,” Maynard says. “Our data suggests there are plenty more species to be documented in the canyon, and we also hope to develop research projects in collaboration with our partners to better understand the mysterious life histories of these poorly understood species.” They still need to find out more about how the Tandayapa Andes toads reproduce and deposit their eggs, and they don’t know why the Mindo glassfrog is thriving in the reserve but not elsewhere nearby, or much about its behavior. For example: Why do they deposit their eggs on the underside of leaves, unlike all other glassfrogs in the genus that lay them on top, and do they engage in combat like other species in the genus?

“The questions one can ask are endless,” Maynard says. “As my wife often points out, I’d rather be in that canyon than anywhere else, any day, anytime.”

![]()