For much of the 20th century humans got really good at dam building. Dams — embraced for their flood protection, water storage and electricity generation — drove industry, built cities and helped turn deserts into farms. The United States alone has now amassed more than 90,000 dams, half of which are 25 feet tall or greater.

Decades ago, dams were a sure sign of “progress.” But that’s changing.

Today the American public is more discerning of dams’ benefits and more aware of their long-term consequences. In the past 30 years, 1,275 dams have been torn down, according to the nonprofit American Rivers, which works on dam-removal and river-restoration projects.

Why remove dams? Some are simply old and unsafe – the average age of U.S. dams is 56 years. It would cost American taxpayers almost $45 billion to repair our aging, high-hazard dams, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers. In some cases it’s simply cheaper to remove them.

Other dams have simply outlived their usefulness or been judged to be doing more harm than good. Dams have been shown to fragment habitat, decimate fisheries and alter ecosystems.

Depending on the size and scope of the project, dam removal may not be an easy or quick fix. Getting stakeholders onboard, raising the funds and performing the necessary scientific and engineering studies can take years before actual removal efforts can begin.

And some projects are controversial and may never get the green light. For decades stakeholders have debated whether to remove four hydroelectric dams on the Lower Snake River in eastern Washington. The dams provide about four percent of the region’s electricity, but also block endangered salmon from reaching critical habitat. The fish are a key food source for the Northwest’s beleaguered orcas.

The debate over the Snake River dams is ongoing, but with each new dam removal researchers are learning important lessons to help guide the next project. One of the most important lessons gleaned so far is that rivers bounce back quickly. Recent research has shown that “changes in the river below the dam removal happen faster than were generally expected and the river returned to a normal state more rapidly than expected,” says Ian Miller, an oceanography instructor at Peninsula College and a coastal hazards specialist.

Miller has worked on studies both before and after the removal of two dams on Washington’s Elwha River, which is the largest dam-removal project thus far. But more projects, including a big one, may soon be grabbing headlines.

Here are four that we’re watching closely that show the diversity of dam-removal projects across the country.

Klamath

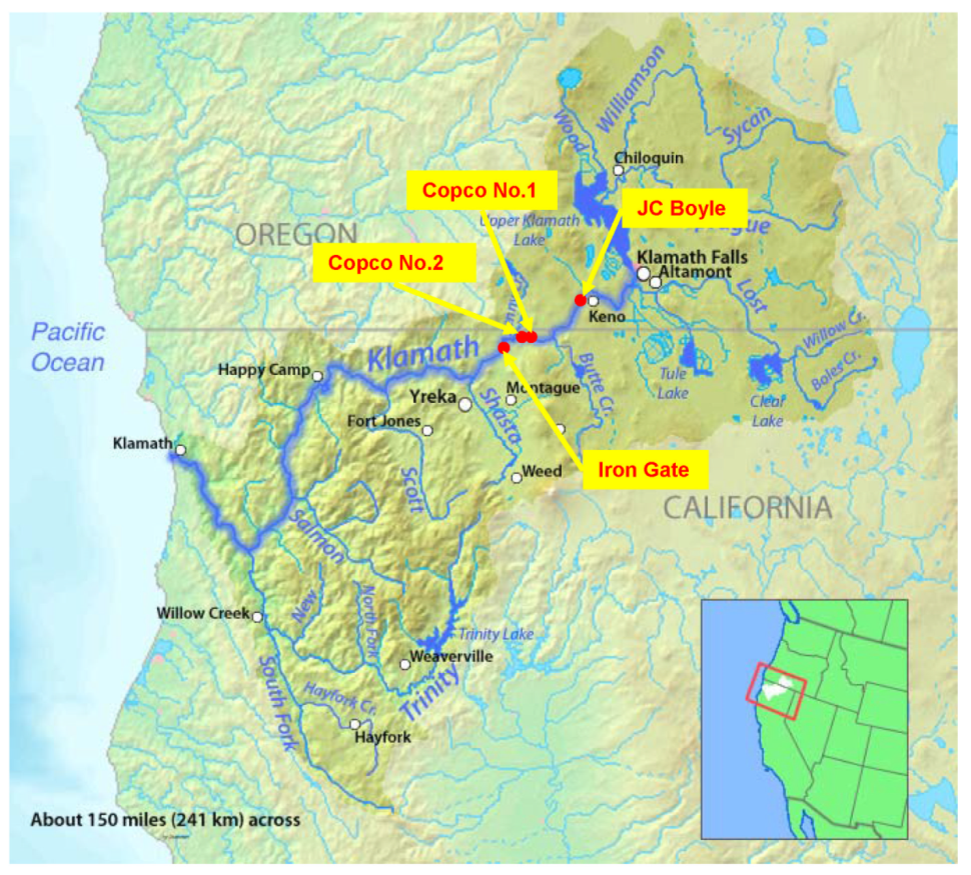

The most anticipated upcoming dam-removal project in the United States will be on the Klamath River in California and Oregon. It’s the first time four dams will be removed simultaneously, making it an even bigger endeavor than those on the Elwha.

“We’ve never seen a dam-removal and river-restoration project at this scale,” says Amy Souers Kober, communications director for American Rivers.

The hydroelectric dams — three in California and one in Oregon — range in height from 33 feet to 173 feet.

Local tribes may be among the most enthused for the dams’ removal. Their communities depend on salmon as an economic and cultural resource, but fish populations began to crash after the first dam on the Klamath River was constructed 100 years ago.

While the removal of the dams won’t make the Klamath River entirely dam-free (there will be two more upstream dams remaining), it will open up 400 miles of stream habitat for salmon and other fish. It’s also expected to help improve water quality, including reducing threats from toxic algae that have flourished in the warm water of the reservoirs.

The project is hailed for the huge coalition for stakeholders that have become collaborators. “This has been decades in the making, with so many people involved, from the tribes, to commercial fishermen, to conservationists and many others,” says Kober. “Dam removals are most successful when there are a lot of people at the table and it’s a truly collaborative effort.”

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and an independent board of consultants are now reviewing the plan for the Lower Klamath Project, a 2,300-page analysis of the dam removal and restoration effort. And the project is also working on receiving its last permitting requirements. If all proceeds on track, the site preparation will begin in 2020 and dam removal in 2021.

Patapsco

On September 11, as the Southeast readied itself for approaching Hurricane Florence, a blast of explosives breached the Bloede Dam on the Patapsco River in Maryland. Crews have been working to remove the rest of the structure and restoration efforts are expected to continue into next year.

The dam — the first submerged hydroelectric plant in the country — was built in 1907 and is located in a state park and owned by Maryland Department of Natural Resources. For the past decade concerns have mounted over public safety, obstructed fish passage and other aquatic habitat impacts from the dam, prompting a plan to remove it.

The removal of the dam is “going to restore alewife and herring and other fish that are really vital to the food web and the Chesapeake Bay,” says Kober. Researchers expect to study the results of this ecosystem restoration for years to come.

There’s another reason to watch this project: The dam’s removal also involves some interesting science and technology. Researchers have employed high-tech drones to help them understand how much of the 2.6 million cubic feet of sediment from behind the dam will make its way downstream and at what speed. With the sensitive ecosystem of the Chesapeake Bay just 8 miles downstream, sediment inflow is a big concern.

“Just the idea the we can fly drones over this extended reach with some degree of regularity means that we can see evidence of sediment movement from the pictures alone,” explains Matthew Baker, a professor of geography and environmental systems at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, who is helping to lead this effort. “We can track the movement just by taking low-altitude aerial photos and we can try to model that within a computer and estimate the amount of sediment and the rate of movement.”

This kind of research lowers the cost of monitoring, says Baker, and can help future dam-removal work, too. “I think it’s going to be employed regularly,” he says.

Middle Fork Nooksack

About 20 miles east of Bellingham, Wash., a dam removal on the Middle Fork Nooksack River is the “next biggest important restoration project in Puget Sound,” says Kober.

The diversion dam, built in 1962, was constructed to funnel water to the city of Bellingham to augment its primary water supply source in Lake Whatcom – but at the expense of fish, which cannot pass over or through the dam.

Since the early 2000s the city, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Lummi Nation and Nooksack Indian Tribe have worked on a plan to remove the dam in order to restore about 16 miles of spawning and rearing habitat for three fish listed on the Endangered Species Act: spring Chinook salmon, steelhead and bull trout.

The primary purpose of the dam removal “is recovery of threatened species,” says April McEwen, a river restoration project manager at American Rivers. “The goal of the project is to provide critical habitat upstream for those salmon species to be able to spawn.” It’s also hoped that more salmon will reach the ocean and help the same endangered orcas affected by the Snake River dams. The whales depend on the fish for food and are at their lowest population in 34 years.

But a critical part of the dam-removal project is continued water supply for the city.

Currently the dam creates a “consistent and reliable municipal water flow,” says Stephen Day, project engineer at Bellingham Public Works. The current project design has identified a new diversion about 1,000 feet upstream where water can be withdrawn with similar reliability but without the need for a dam.

The design phase of the project is currently being finalized, and McEwen says they hope to have all the permits by March 2019 and the dam removed later the same year. But first, the project still needs to secure some needed state funds.

The dam removal is “a really big deal” for the entire Puget Sound ecosystem, says McEwen. “Salmon are keystone species. If their numbers are down, we all suffer, including humans and especially orca whales.”

Grand

A project that has been in the works for a decade could put the “rapids” back in Grand Rapids. More than a hundred years ago, the construction of five small dams along a two-mile stretch of the Grand River in the Michigan city drowned the natural rapids to facilitate transporting floating logs to furniture factories along the banks.

Those factories long ago closed, and the aging dams are now more of a safety hazard than a benefit for the city.

The idea of removing the dams came as part of a larger effort initiated in 2008 to green the city. “Early on the main focus was recreation, looking at ways to bring back rapids for kayaking,” says Matt Chapman, director and project coordinator of the nonprofit Grand Rapids Whitewater, which has been leading the river-restoration effort. “But as the project has evolved and as we’ve learned and studied the river, we’ve realized there are so many other benefits to a project like this.”

“The more we found out about the river, the more we realized how impaired it is biologically,” says Wendy Ogilvie, director of environmental programs at the Grand Valley Metropolitan Council. “We hope through the revitalization there will be some recreational opportunities, but a lot is fish passage and a better habitat for native species.”

The dams set to be removed may be small — the largest is about 10 feet tall — but the project isn’t simple. For one thing, the presence of the Sixth Street dam, the tallest, has blocked the further invasion of parasitic sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus), which have spread from the Atlantic Ocean throughout the Great Lakes over the past two centuries. The project is working to create a new structure that will prevent the lamprey from migrating further upstream and preying on native fish after dam removal.

Project managers discovered that the federally listed endangered snuffbox mussel (Epioblasma triquetra) also makes its home in this stretch of river. The project hopes to carefully remove and relocate the mussels to suitable habitat during the construction process, which is expected to take about five years. The mussels may be returned after construction and restoration. The dam removal is also expected to help state-listed threatened lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) return to their original spawning grounds upstream and benefit smaller fish like logperch, which have been blocked by the dam and are vital for mussels.

The river-restoration process is also spurring a greater revitalization effort along the riverfront to provide more accessible green public space and economic opportunities.

“It’s not just restoring the river, but also how the community gets to the river from the neighborhoods,” says Chapman.

He says they hope to have all the necessary permits in hand to begin working on habitat improvements in the lower part of the river next summer, including finalizing a plan for the mussels’ relocation. It will likely be another three or four years before the sea lamprey barrier is complete and the Sixth Street dam will be removed following that.

Much work has been done over the years to clean up the river and curb pollution, says Ogilvie. The next step is helping to restore the ecology and recreational opportunities. “The best part about the project is having people value the river and think of it as a resource,” she says. “If we could see sturgeon coming back up the river…that would be pretty amazing, too.”

Previously in The Revelator:

The Elwha’s Living Laboratory: Lessons From the World’s Largest Dam-removal Project