President Trump’s determined pivot away from climate action probably means that the low-lying Maldives Islands will submerge sooner, droughts in sub-Saharan Africa will more rapidly intensify and urban heat waves will get hotter and more frequent. Around the world, failing to confront climate change will affect vulnerable people first. The rest of us won’t be far behind.

But sometimes the act of combating global warming can actually have its own victims, too. Few people understand this better than the Ngäbe-Buglé, the largest indigenous group in Panama.

Early last year Bulu Bagama, a Ngäbe-Buglé farmer, paddled the Tabasará River in a dugout canoe along the shore of his natal village, Kiad. He seethed. Followers of the indigenous Mama Tata religion were expected in the village soon. He said he’d be on dry land harvesting cassava and cooking fermented corn to feed them if the government hadn’t destroyed his orchards of bananas, oranges, mangos and avocados — if the Honduran construction company GENISA hadn’t flooded sacred petroglyphs chiseled by ancestors into boulders midstream in the river. Instead he was floating with a foreigner above flooded houses he’d built, flooded fields he’d planted and the flooded cemetery where he’d buried his parents. We paddled above it all on several yards of murky water.

“If God did this, if he filled this with water, it’d be one thing,” said Bagama, eyes ablaze under a hand-woven straw hat. “But it wasn’t God who did this. It was done by man, and someday, he’ll pay.”

The proximate cause of Bagama’s misery was not just one man, but Barro Blanco, a 20-story-tall hydroelectric dam three miles from where he canoed. The company Generadora del Istmo, better known as GENISA, had built it at the request of the Panamanian government — purportedly to help fight climate change.

The administration of Martín Torrijos, Panama’s president from 2004 to 2009, first proposed the Barro Blanco Dam in 2006. The project came to fruition under the administration of his successor, Ricardo Martinelli, a real estate mogul-turned-politician sworn in as Panama’s 36th president in July 2009. A man in the Trumpian mold, Martinelli promised to make Panama more business-friendly and improve the country’s infrastructure.

Meanwhile, a new sail-shaped building, Trump Ocean Club, was rising slowly into the sky above Panama City. It was Donald Trump’s first international real-estate venture. When the Panamanian president and American president-to-be met at the sky scrapper’s ribbon cutting, they traded public praise. “Everything you touch turns to gold,” Martinelli told Trump, according to The Christian Science Monitor. Trump called Martinelli a “great businessman,” and “a great president.” Trump invited Martinelli to his own inauguration in 2017, even though the former Panamanian leader was by then living in a luxury condo in Miami after fleeing embezzlement and wiretapping charges while in office. (He has since been arrested and is battling extradition from the Miami Federal Detention Center.)

Trump had not yet become a climate denier in 2009. That year he and scores of other business leaders signed a letter in the New York Times urging President Obama to take “meaningful and effective measures to control climate change.” Martinelli likewise had expressed concern about climate change, which he’d called “the gravest expression of a crisis triggered by excesses in the exploitation of resources.”

Perhaps that’s one of the reasons why Martinelli’s administration staunchly championed the Barro Blanco dam. In fact, shortly after Martinelli took office, the government’s electricity regulator dramatically expanded the plan, increasing its capacity by 50 percent, to 29 megawatts, or 2 percent of Panama’s electrical needs. The enhancement also raised the level of the required reservoir behind the dam, preordaining the destruction of Bulu Bagama’s house and crops.

Under Martinelli’s watch the United Nations registered Barro Blanco in the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism, a program encouraging investors in wealthy countries to finance carbon reduction in poor ones. CDM projects earn one Certified Energy Unit, for each ton of CO2 they displace, redeemable on carbon markets, such as the European Trading Scheme. Barro Blanco was projected to cut carbon dioxide production by 1.5 million tons in two decades of operation, according to UN documents.

Opponents of the dam say that without the UN stamp of approval and the income promised from energy units, Barro Blanco might never have been built. It most likely helped with the financing. Two European Banks, the Dutch Development Finance Company and the German Investment and Development Corporation, each invested $25 million. Ironically, Panama later withdrew from the CDM program in 2016 after facing criticism over misrepresentations in its paperwork.

By then, the dam’s concrete had long since dried.

In January 2017, while the U.S. presidential inauguration transfixed most of the world, the residents of Kiad were preparing for their own ceremony. Pilgrims from across Ngäbe-Buglé territory would arrive soon, as they do every year to pray and worship. But this time would be different. In past years several hundred guests had always arrived. Now no one knew how many would come or where they’d stay. The purpose of the event was to worship by the petroglyphs, but the carved boulders could no longer be seen. They’d been completely submerged when the reservoir was filled months earlier. The flat land along the previous shore was also underwater, leaving little good camping space.

Many Ngäbe-Buglé practice Mama Tata, an indigenous religion that combines Christianity and animism. They believe their ancestors encoded wisdom in the cryptic markings scored into the boulders in Kiad and elsewhere in their territory. Ricardo Miranda, a resident of Kiad and an ardent opponent of the dam, told me that the drawings connect them with forefathers before the Spanish conquest. They’re Mama Tata’s sacred texts and repositories of indigenous wisdom. The dam is “erasing our history,” he said angrily. “How can I talk about that with younger generations if I can no longer tell them, here it is.”

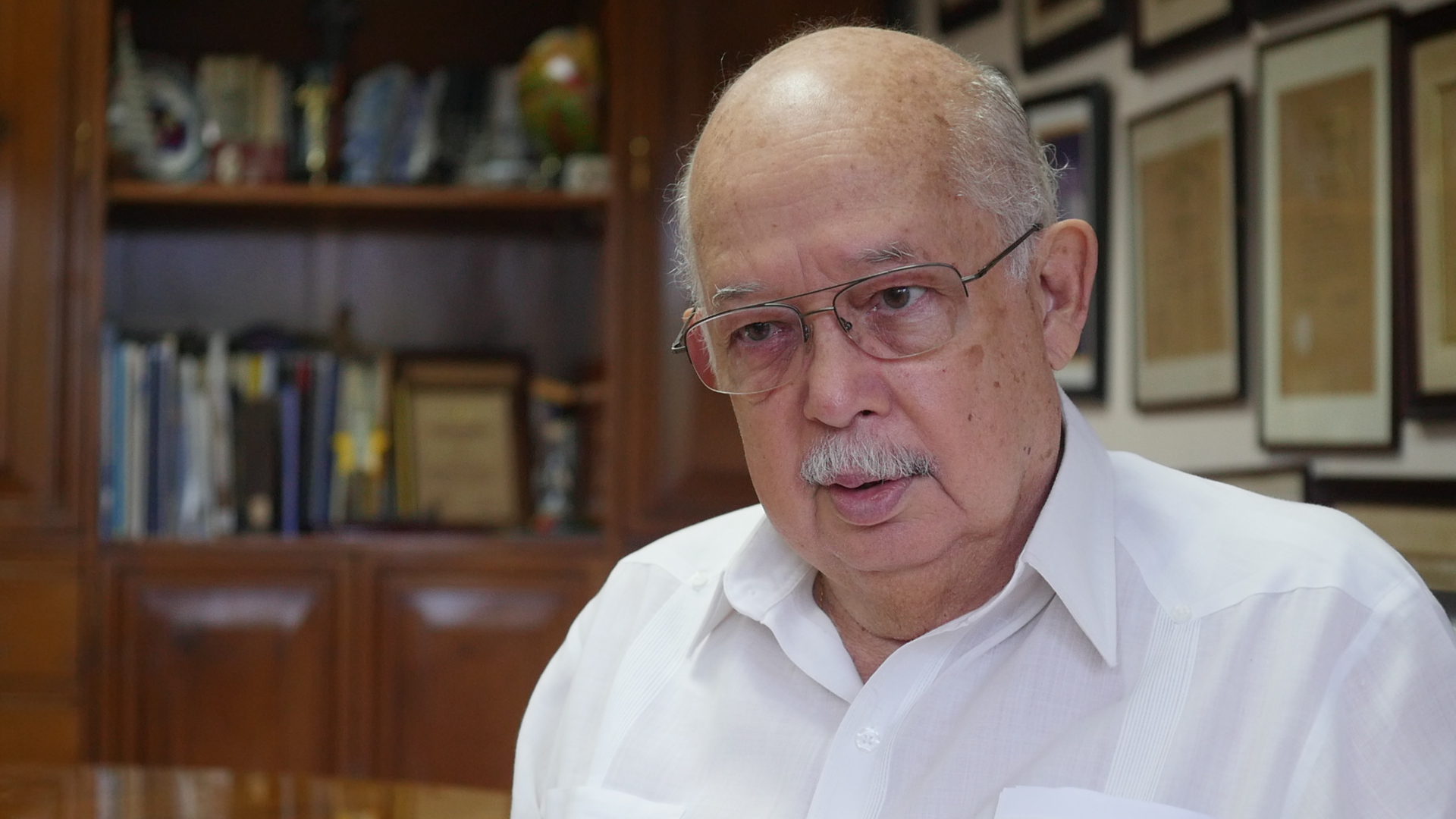

“Some people say, well, take the stones out elsewhere,” said Eduardo Vallarino of the boulders in a meeting in his Panama City office in January 2017. Vallarino is president and CEO of PanAm Development, which wants to build a smaller hydroelectric dam 15 miles from Barro Blanco, also in the face of indigenous protest. He was Panama’s ambassador to the United States in 1990 and once ran for president. He accused Barro Blanco’s detractors of making up spurious objections to the project. “They’re looking at everything they can in order to stop things.”

But the protests are nothing new. Panama’s indigenous people have long battled against incursions on their territories. Successive governments sought for decades to dam the Tabasará River before Martinelli’s administration succeeded. The indigenous people opposed every attempt, sometimes with demonstrations, construction-site occupations and blockades of the nearby Panama American Highway. Indigenous people were kept out from the first public meetings about Barro Blanco, in 2007.

At times the project has sowed divisions within the community. Still, the Ngäbe-Buglé have challenged the dam in Panamanian courts and — failing that — petitioned for help from international human-rights organizations. A 2014 report written by the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples admonished Panama that “Ngäbe people should not be flooded or adversely affected in any way without the prior agreement of the representative authorities of that people….”

GENISA had long insisted that that few Ngäbe-Buglé would even be inconvenienced, and that, in the words of its 2011 report on the social and environmental impacts of the project, the “land and riverbank that will be submerged by the reservoir is not currently under cultivation, nor used for any other productive use.” But by then, changes in the dam’s design guaranteed that some houses and crops would be flooded in many feet of water. And that, according to a study conducted on behalf of the project’s European funders, was a fact about which residents of Kiad and other communities were kept in the dark.

Opponents of Barro Blanco have exhausted legal options in Panama. But they continue fight the dam in the court of local and world opinion, by staging protests and by petitioning help from international rights organizations, such the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Last September they won a small victory when a Panama court acquitted three Ngäbe-Buglé leaders, including Ricardo Miranda, of charges that they’d disrupted activities at the dam during protests.

Ironically, the dam’s touted environmental benefits are increasingly in doubt. A growing scientific consensus says that dams are sometimes of marginal value for the climate. Rotting organic matter in the soil they flood releases methane, a gas that warms the planet many times more powerfully than carbon dioxide. A 2012 paper in Nature Climate Change called tropical dams “methane factories” that “can be expected to have cumulative emissions that exceed those of fossil-fuel generation.”

But tropical dams keep getting built anyway. Barro Blanco is only one of the latest, and even its lofty promises now ring hollow.

In January 2017, two days before the Mama Tata ceremony, Manalo Miranda put up an open-air pavilion made from spindly tree trunks and corrugated iron.

The reservoir had filled up several months earlier, after GENISA technicians had shut the dam’s flood gates. The rainy season was due any day and arriving pilgrims would need shelter. Goejet Miranda walked to a thatched hut above town, to charge his phone. A solar panel there provides Kiad’s only electricity.

But there was no room to plug in. The panel’s output was maxed out.

The one benefit that Barro Blanco might have provided the Ngäbe-Buglé — electricity — is in limited supply.

Grossman’s reporting in Panama was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and the Frank B. Mazer Foundation.

© 2018 Daniel Grossman. All rights reserved.