Artist Ralph Steadman has become the ultimate recycler.

Until recently, the dirty water the 81-year-old satirist used to clean his paint brushes each day would get dumped down the sink, never to be seen again.

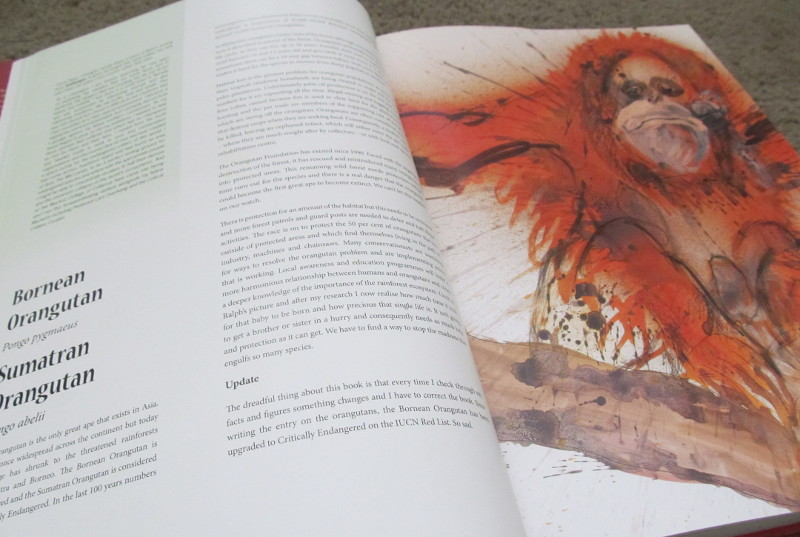

But last year Steadman started pouring his water glasses onto something else: large pieces of paper on his studio floor. After the dirty water has dried for a day or two, he examines the faint colors and patterns — like a giant Rorschach inkblot — and an image forms in his mind. His paintbrushes come out again and he swirls and splats color and ink until the portrait of an endangered animal emerges.

“Picasso had his blue period,” he tells me. “I’ve entered my dirty-water period.”

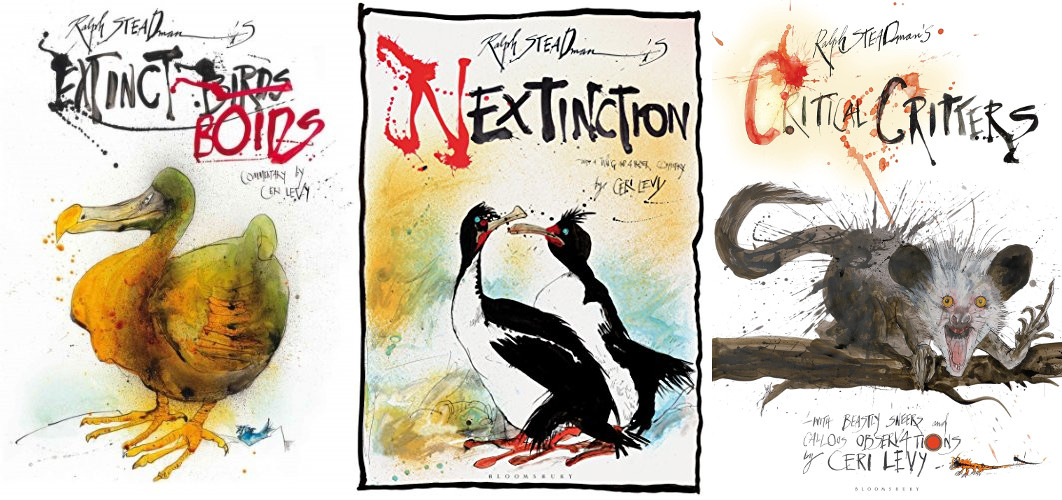

The resulting paintings — 100 of them — can be found in the new book Critical Critters, published Sept. 26 by Bloomsbury, with proceeds from each sale benefitting the World Wildlife Fund.

The watery book marks Steadman’s third collaboration with writer, filmmaker and conservationist Ceri Levy. “That’s us,” Levy says. “A team built out of filth.”

The book is packed with portraits of endangered animals — giant pandas, tigers, chimpanzees, vaquitas, pangolins and dozens of other species — all depicted in the wild, paint-splattered technique Steadman made famous through his collaborations with gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson. Next to each painting, Levy provides text (both scientific and comic) about the various species. Alongside that information he contributes a running narrative about the process the duo used to develop the book and its contents.

That process involves Steadman and Levy trading a constant barrage of jokes, insults, barbs, slings, snipes and burns, along with the more-than-occasional pun.

That process involves Steadman and Levy trading a constant barrage of jokes, insults, barbs, slings, snipes and burns, along with the more-than-occasional pun.

“I guess that’s why we work well together,” Steadman laughs, “because we enjoy the hurt.”

The duo first teamed up a little over six years ago, when Levy asked Steadman to provide a single painting for an art exhibition about extinction. Steadman produced dozens. That led to their first book, Extinct Boids (2012), which contained portraits of bird species that are no longer with us. They followed it in 2015 with Nextinction, about the bird species that could be next to fall into extinction if the world doesn’t take action. Now they’ve finished the series by turning their pens and keyboard to the rest of the animal kingdom, tackling mammals, reptiles, fish, insects and even a plant or two.

(There are still a couple of birds in the new book. Steadman likes drawing beaks.)

Despite the heady topics of endangered species and extinction, Critical Critters — like the two books before it — is remarkably funny while remaining deeply informative. “We’ve always maintained that you’ve got to make people laugh in order to engage them,” Levy says. “If we just tell people, ‘you’re all dreadful bastards, you’ve screwed it all up, and now look what’s going to happen,’ people go, ‘yeah, whatever.’ But if you make them laugh, you’ve got a chance.

“That’s all you’re trying to do is inform people,” he continues. “But you’re trying to bribe them by giving them a good joke or two. And then they come to the table.”

Both creators say they feel they’ve accomplished something over the course of their collaboration and friendship. “Three hundred paintings down the line and we’re still talking to each other,” Levy says. “The weird thing is that one painting has now turned into a trilogy. We’re calling it the ‘gonzovation’ trilogy.”

“He stole that word off of me,” Steadman accuses gruffly, as the three of us talk over Skype.

“He stole that word off of me,” Steadman accuses gruffly, as the three of us talk over Skype.

Levy sighs, exasperated. “As soon as he’s in public, he says I’ve stolen everything.”

“Ceri just causes trouble,” growls Steadman. “He’s a bit like one of these critters. He creeps about and smashes things and then he eats somebody’s sandwich.”

Even with the book done, the two still trade their fair share of barbs.

So — what exactly is “gonzovation?” Levy says a gonzovationist is just an alternative conservationist. “I think it means the normal, regular people who are trying to help the world of conservation in some way,” he explains. “Everyone can do something to help animals, creatures, the planet, nature, and we don’t have to have, you know, university degrees. We can partake in conversation.”

Steadman interrupts. “What do you mean we don’t have university degrees?”

“Yours isn’t real! Did you show up for the tests?”

“I’m a BSc,” says Steadman, mock-indignant.

“I know what the BS stands for.”

“Bloody silly.”

“Gonzovation,” Levy finally continues, “allows the rest of us who aren’t in those hallowed halls of conservation to have a chance to do something. That’s the important thing. I think everyone’s fed up with clicking the ‘like’ button on Facebook or donating three dollars a month to help this or that animal. We need to find a way to participate and be hands-on.”

Both say working on the trilogy has opened their eyes. “I’ve learned an awful lot,” Levy says. “I had no idea when we started just how screwed the planet is at the moment and how many people are trying to screw with it. We’ve all got to do something. We can’t do nothing anymore. It could mean taking out the recycling. It could mean planting a tree that butterflies like. It could mean getting really good pollinating plants. We can all do things that help.”

Steadman says he’s stunned to find out why some of these species are endangered. “One of the things that amazes me, is that people have a need to go out hunting still.”

Even with three books under their belts, Levy feels there are still important things to learn, not just for himself but for the entire conservation community. “Conservation needs to find a way to get more people to do things that will help,” he says. “We need to engage. We need to find a way to make people feel they’re part of it, so they’re not disassociated from conservation projects. That’s the million-dollar question for conservationists today: how do we make people gonzovationists?”

The process that led to the creation of Critical Critters may hold part of that answer: “It’s just teamwork,” says Steadman. That’s what works in conservation — only maybe with fewer puns and snipes.