On most levels, Nepal and Namibia appear to have very little in common. Nepal is a landlocked Himalayan nation with an abundant supply of forests and water, while Namibia is a desert country about six times larger, with a long coastline on the Atlantic Ocean. People in Nepal rely primarily on subsistence agriculture and forests for their livelihoods, while people in Namibia mostly rely on grazing lands and livestock. Nepal was never colonized and remained closed to most outsiders until 1951. Namibia was colonized in 1884 by Germany, then South Africa, only gaining independence in 1990. Nepal, according to the United Nations, has one of the densest human populations in the world at 203 people/sq km, while Namibia has just 3.1 people/sq km, making it the second least dense country in the world, after Mongolia.

But if you look a bit closer, you’ll find the two countries do have something in common. While both were in desperate need of conservation efforts just a few decades ago, with experts making dire projections about the decimation of local wildlife and natural resources, now they’re conservation success stories because both countries effectively incorporated community-based approaches into their national biodiversity strategies. Today nearly 40% of Nepal’s forests are managed by communities, and 20% of Namibia is protected in community wildlife conservancies.

As I found in my time in both countries, one person working with local communities set the process in motion.

Dire Circumstances Lead to Change

The origin story of community forestry in Nepal began when forester Tej Bahadur Singh Mahat was transferred to Sindhupulchowk District in 1973 to be the district forest officer.

Upon his arrival, he came across a file left by his predecessor detailing ongoing issues, included a letter from a village in the district. It said they weren’t willing to cooperate with the forest officer any longer, because a previous officer had allowed forest they relied on for fuelwood and fodder to be cut for timber and sold in Kathmandu.

Mahat went to visit them and made a plan with Nil Prasad Bhandari, the village chairperson: If the community took on the responsibility of managing the forest, he would not allow any outsiders to use it.

It worked — and influenced others. Soon after, the Australian Forestry Project, which had come to the area to start a new venture, saw the success of the work the community and Mahat were doing and built its program based on the model they’d adopted.

In Namibia the idea for community involvement came in 1983, when Garth Owen-Smith, the founder of the Namibia Wildlife Trust (now called the Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation), visited with local leaders in Kaokoland, in the northwest. He knew the leaders well, having worked there for many years. He realized that poaching was getting worse and that the government and NGOs didn’t have the resources to patrol such vast areas.

Owen-Smith asked Joseph Kagombe, a local leader, for help. Together they came up with a plan that began with choosing respected men in the community to be community game guards, who would monitor both wildlife and human activities and conduct conservation extension work in their communities.

These were just the beginnings, but the seeds they planted decades ago have grown and expanded.

Today Nepal is home to more than 22,000 community forestry groups, consisting of members from over half of the households in Nepal. The area under community control has tripled in the past two decades, with local communities managing about one-third of the country’s forests. Forest degradation and loss have declined significantly and in some places reversed. Between 1992 and 2016, forest cover increased from 26% to 45%.

In Namibia 86 communal conservancies involving more than 200,000 people protect over 20% of the land. The community wildlife conservancies protect the largest free-roaming black rhino population outside protected areas and an elephant population that has tripled between 1995 and 2016, from 7,500 to 22,800.

In both countries the success of community conservation has supported the creation of, and experimentation with, multiple types of community-based conservation interventions. In Nepal these include, in addition to community forestry, buffer zones around national parks, conservation areas, leasehold forestry, protected forests and community conserved areas. In Namibia these include national park community conservation associations, community forests, community rangeland management areas and community fish reserves.

Lessons From World’s End

I consider myself extremely lucky to have worked in Nepal since the 1990s. My experiences with conservation and communities there give me more hope for the future than most of my colleagues have in various places around the world.

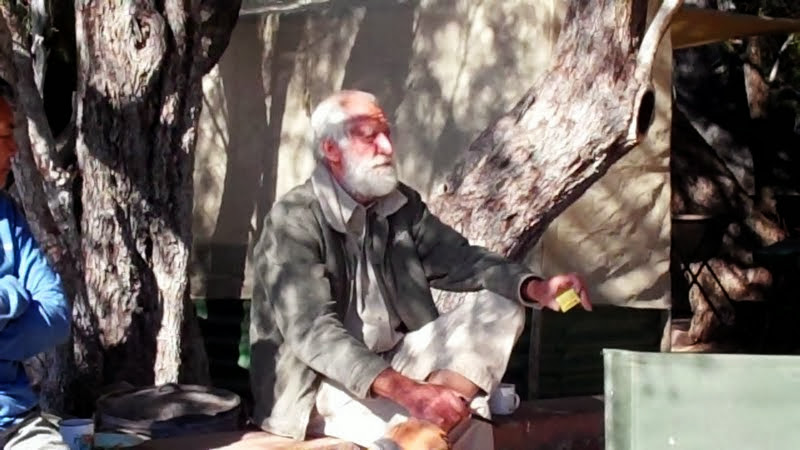

But I didn’t know how it had all begun until recently. While I haven’t yet had the pleasure of meeting T.B.S. Mahat, I recently learned he’s publishing his memoirs. Owen-Smith passed away in April 2020, but I did have a chance encounter with him a few years ago at his camp in northwestern Namibia, Wereldsend (World’s End), during a trip teaching biodiversity policy to a group of international students. We spent a memorable evening sitting around the campfire while he described the history of the wildlife conservancies. At one point, he listed the leaders, in addition to Joshua Kagombe, who’d helped create community-based conservation in Namibia, saying it was important that we remember their names.

During his story I got to thinking: What can we learn from these two countries’ experiences?

The origins of community conservation in Nepal and Namibia put our own individual efforts into a larger context and remind us that our actions on the ground, to save a habitat or species, can have a great impact. These are powerful models, but they can take a long time to come to fruition — during a biodiversity crisis that makes us feel we don’t have the luxury of waiting.

In today’s world we often feel powerless when it comes to effecting change on a large scale. We often assume successful projects have arisen from top-down policies, without realizing that policies come after someone has proven the model can work by taking the first step from the bottom up. Individuals make a difference — it just takes time for actions to cascade into greater change.

Origin stories like these show us that conservationists and communities, working together in specific places and times, can create some of the most robust conservation models in the world. And that’s a lesson we can all hold in common across diverse countries, habitats, species, and ecosystems.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.

![]()