Six years ago Blacksand Beach stood out as one of the prettiest beaches in Prince William Sound, Alaska. You could picnic or pitch a tent on its flat mix of gravel and moss, near an alder thicket busy with warblers. The birds’ singing joined a chorus of falling water, including a small stream along the beach and cascades thundering down nearby glacier-capped mountains. Harbor seals drifted past on icebergs and mountain goats scampered on cliffs above. A short stroll led to the edge of the Coxe Glacier, a four-mile river of ice that flows from the mountains down to the ocean. You could walk up and kiss it.

But today much is changed. The Coxe Glacier has shrunk away from one mountainside, leaving a massive wall of loose rock perched above the beach. Almost every year sections of the wall collapse into the glacier’s river, temporarily damming it. When the river inevitably breaches the dam, a sudden flood rages down the beach, burying it in furniture-sized boulders and loose rubble. The few trees that remain have been slashed open by speeding rocks.

Many people now avoid the beach, including most of the eco-tour kayak and hiking companies that used to bring visitors here every year.

The events at the remote and relatively small Coxe Glacier require further scientific study, but experts say they reflect a rise in landslides near retreating glaciers in Alaska and other mountainous areas of the world.

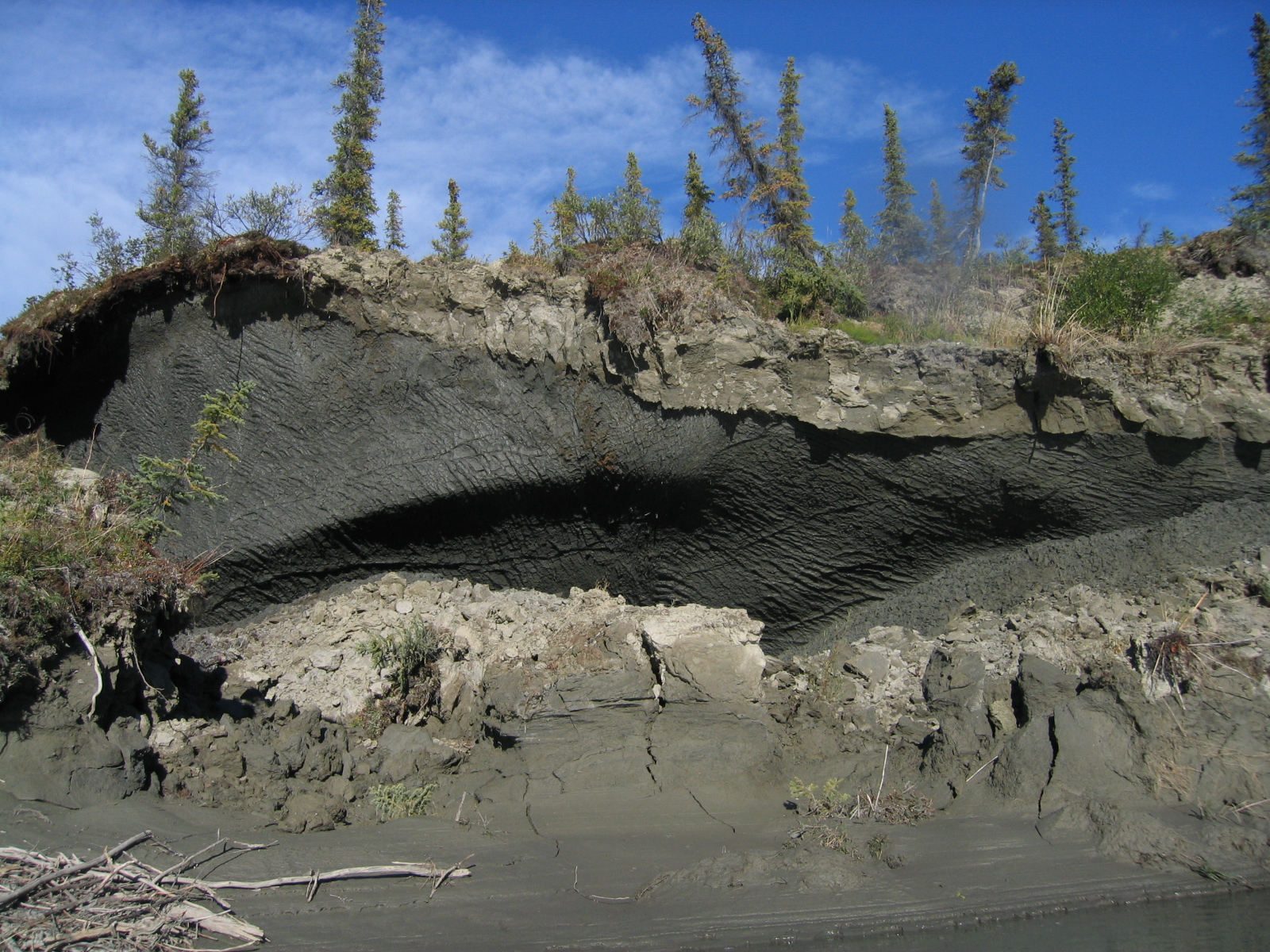

As glaciers retreat with ever-increasing speed, ice that for millennia has held up potentially unstable mountainsides disappears, a process called debuttressing. Geologists debate specifics of the process, but they acknowledge it contributes to slides, some of which are big enough to block rivers or trigger deadly tsunamis in lakes or oceans.

It’s a potentially dangerous side effect of climate change that requires more research to fully understand, says Bretwood Higman, executive director of the nonprofit science advisory group Ground Truth Alaska. “It’s certainly an evolving field,” he says.

But Higman has studied Alaskan tsunamis and landslides for two decades and believes the evidence is strong that receding glaciers can destabilize mountain slopes.

And that can produce serious hazards. In May Higman and more than a dozen other geologists warned residents of the Prince William Sound community of Whittier that an even larger mountainside near Coxe Glacier appears vulnerable to collapse. This one, near the retreating Barry Glacier, could slide directly into the ocean, producing an initial wave up to 600 feet high and sending a potentially destructive tsunami toward the city, 50 miles away.

A Wide-ranging Threat

Higman says the potential Barry Glacier landslide carries markers similar to a massive 2015 event in the remote Taan Fiord in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, 150 miles southeast of Prince William Sound. It occurred near a similarly retreating glacier and was also associated with debuttressing. The slide sent a 633-foot wave up a nearby mountainside and triggered a tsunami that leveled eight square miles of forest.

Responding to this May’s warning, Chugach National Forest officials advised the public to avoid the famously scenic Harriman Fiord, a staple for recreation and tourism activity that provides revenue across south-central Alaska. State and federal geologists have spent the summer rushing to learn more, protect Whittier residents and maybe restore a sense of stability for local tour operators.

“I’m impressed by the response,” says Higman, who works with the Forest Service and other agencies to assess the danger.

He says the unpredictable nature of landslides presents a challenge, as some debuttressed mountainsides let loose catastrophically, while others remain precariously in place for decades or longer. This complicates public messaging and makes life hard for residents and tour operators, who want to know they’re taking people to safe locations.

Ninety miles from Whittier, on the eastern side of Prince William Sound, city officials in Valdez now warn that recent events at the Valdez Glacier may pose a similar debuttressing threat, albeit on a smaller scale. This summer two large “separation events” detached a half-mile section of the glacier, which may have undermined the stability of adjacent slopes and increased the risk of future landslides.

“It was wall to wall,” says the city of Valdez’s emergency manager Aaron Baczuk, describing how the ice broke away across the entire width of the fiord. “It completely severed and then floated out into the lake.”

Baczuk has teamed with local outfitters to release videos warning boaters about travel in the area, including the possibility of landslides traveling into the lake and triggering dangerous waves. They take the potential threat seriously: Three kayakers died in 2019 after ice fell into the lake.

The Permafrost Factor

Farther south safety concerns at Alaska’s Glacier Bay National Park led to a 2017 report in which geologists described 24 landslides they believe were at least in part climate-related.

In a normal year, cruise ships carrying up to 4,000 passengers transit Glacier Bay’s steep-walled fjords hundreds of times. Park officials have acknowledged that landslides could strike the water and jeopardize these ships and tourists.

“Glacier Bay is characterized by a lot of steep slopes,” says Erin Bessette-Kirton, a geological engineering graduate student who has researched local slides. “The mountains go from sea level to high elevations very quickly, making them susceptible to landslides.”

A 2019 assessment mapping landslide hazards in Glacier Bay identifies retreating glaciers as a factor, but also points to thawing of high-elevation permafrost.

In this process frozen rock and water that have bonded mountain peaks together soften as temperatures rise, leaving slopes more susceptible to rainfall, snowmelt, earthquakes and other forces.

“The thawing causes changes in rock strength,” says Bessette-Kirton. “It allows water and heat to travel deeper into the rock. And it transfers freeze-thaw processes into deeper material, causing unstable conditions.”

Thawing alpine permafrost is suspected in a monster 2016 landslide high in Glacier Bay’s backcountry, which dumped over six miles of debris onto Lamplugh Glacier. Geologists estimate the pile is the size of 60 million mid-size SUVs. It flowed within a few miles of Johns Hopkins Inlet, a common destination for cruise ships. Researchers say that the slide would have been catastrophic for cruise ships and other visitors — including subsistence users, recreationists and park staff — if it had dropped directly into the water.

Back in the Prince William Sound region, five large landslides potentially linked to thawing permafrost have torn away from high peaks in the Chugach Mountains during the last two years. One on Yudi Peak, near the town of Girdwood, left a mile-long trail across an area frequented by a local helicopter ski company.

Higman agrees that the “big black splotches” that landslides increasingly deposit on high mountain glaciers — which are visible in satellite imagery — are consistent with thawing alpine permafrost, but he cautions that the story is not always that simple.

“There’s a lot going on in these mountains,” he says. Rainfall, snowmelt, rising temperatures, tectonics and earthquakes all exert their own pressures, along with debuttressing from glaciers and thawing of permafrost. “Climate change underlies several of those forces, but any one of them may act like the straw that broke the camel’s back when it comes to landslides.”

In this sense, just as it’s hard to blame any specific hurricane or wildfire solely on climate change, it can be hard to pin specific landslides to climate.

Yet thawing permafrost has been tied to a growing list of examples across the globe. Researchers speculate it factored in a massive 2017 landslide at Pizzo Cengalo in the Swiss Alps that killed eight hikers and destroyed parts of the village of Bondo. It has also been implicated in events in the Himalayas, Andes, Greenland and the Canadian Arctic, where thousands of landslides were recently linked to thawing permafrost. Recent work by Bessette-Kirton also links it to landslides in Alaska’s Saint Elias Mountains, north of Glacier Bay.

Unfortunately, just as in instances of debuttressing near receding glaciers, the remoteness and wide distribution of alpine permafrost means landslides often occur in areas where no prior monitoring has been conducted.

“It’s often in really difficult terrain that is hard to access,” says Bissette-Kirton. “And it’s not visible at the surface, so you need temperatures gauges in place and a long-term record to detect changes.”

To address the dearth of hard data, U.S. Geological Survey researcher Jeffrey Coe recently proposed monitoring five “bellwether” sites in the Himalayas, Alps and other areas where the intersection of landslides and thawing permafrost seems most likely.

Compounding Factors

The swift changes being brought about by warming temperatures will always put multiple disruptive forces at play at the same time.

Take, for instance, the deadly 2013 ”Himalayan tsunami” in India. On the surface it appears to have occurred when record-setting rainfall, which has been tied to climate change, swelled the banks of the glacier-fed Chorabari Lake. When the water breached a moraine that formed the lake’s barrier, it washed away scores of villages and killed more than 6,000 people. But research shows retreat of the Chorabari Glacier may have also played a role in the disaster. When it melted it no longer buttressed the moraine, making its collapse more likely.

Chorabari Lake highlights yet another piece of the puzzle. Recent NASA research shows glacial lakes have expanded 50% worldwide due to the accelerating loss of glaciers. Changes to the lakes can cause dangerous instability.

As glaciers retreat, they can trap pools of water behind ice or piles of debris. These pools are called glacial lakes. As the planet warms, glacial lakes are growing — since 1990, the volume of these lakes has increased by about 50% globally. https://t.co/5ptHD06dUw pic.twitter.com/8i1TWb3tHR

— NASA Earth (@NASAEarth) August 31, 2020

Higman points out that these lakes form higher in mountain terrain, where they’re susceptible to landslides caused by shrinking glaciers or thawing permafrost.

There’s no clearer example than Lake Palcacocha, high in the Peruvian Andes, where in 1941 falling ice sent a tsunami across the lake, breaching its barrier and sending a wall of water into the city of Huaraz, killing 1,800 people. That was before the modern recognition of climate change, but today melting glaciers have expanded the lake to many times its 1941 volume, and tens of thousands more people now live below it. Today safety officials liken the specter of landslides or falling ice entering the lake to a devastating “timebomb.”

Such dangers drive Higman and others to continue probing for answers in places like Barry Glacier. He says that, in the past, studying glaciers and mountains required thinking on a time scale of thousands of years, but climate change has reduced the scale of events to decades or even years.

“It would be nice to get ahead of that curve and understand these processes better,” he says. “And maybe by putting in place mitigations we’ll be able to tell a positive story in the future.”

![]()