Adapted from the books Youth Change Agent by Keith Strickland and Before the Streetlights Come On by Heather McTeer Toney.

A change agent cannot free someone from something they won’t release. Before a change agent can work on changing youth behaviors, they have to change the youth’s beliefs. A person’s beliefs are much more deeply rooted than most of us realize. Our beliefs guide our actions, morals, ethics, and norms. Everything we do is motivated by something we believe.

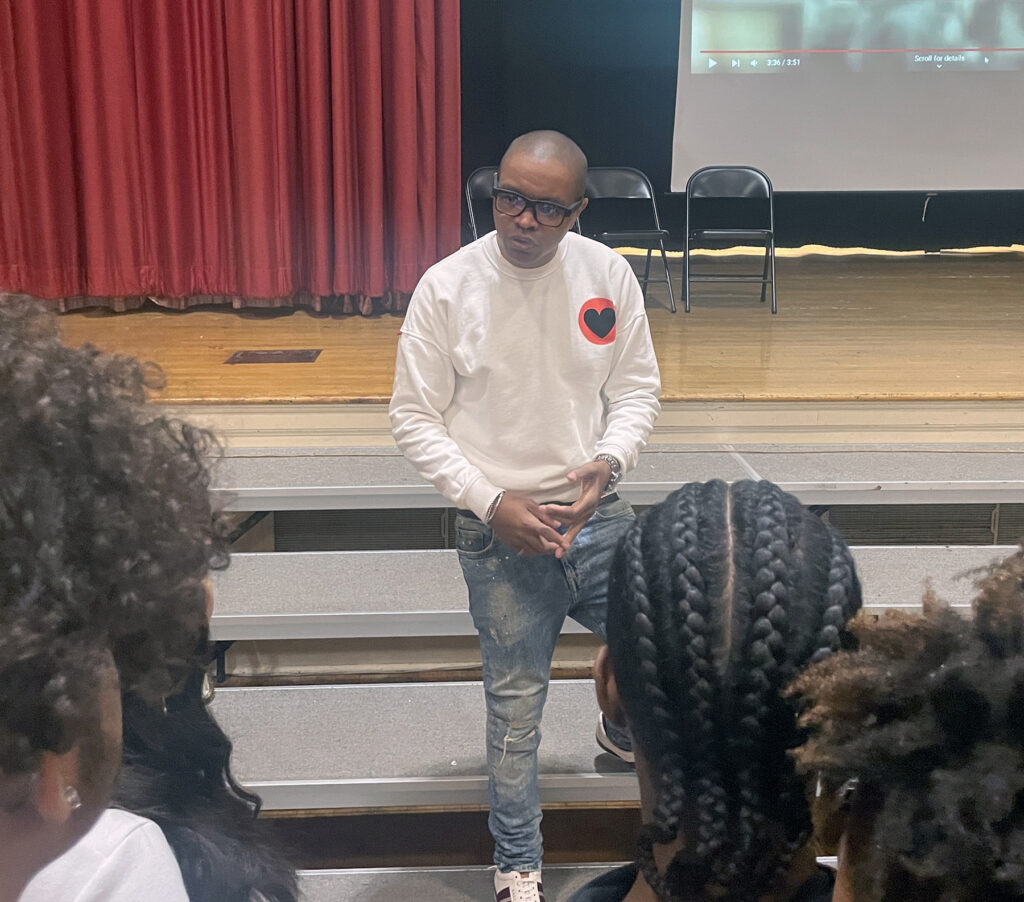

Case in Point

Growing up, we had very few food choices in our community. We had a fast-food burger place at one point, but it closed after multiple people were killed in the parking lot in a short period of time. We also had a pizza chain restaurant, but it also closed after it was robbed over and over. We had a restaurant that sold fried chicken, which we all ate pretty much daily. When I was almost thirteen years old, a hot-wing restaurant opened. I was the first customer. Chicken was my favorite food because I ate mostly chicken. The thought of chicken served in more than a dozen flavors was like heaven to me. Now, after I’ve experienced food from around the world, I’ve come to realize I do not like hot wings or fried chicken nearly as much as I thought I did. In the hood, we are forced to eat certain foods because it’s all we have, but you never really know what you do or don’t like if you’ve only had limited exposure.

A few years later, I opened a barbershop in our neighborhood and a car detailing shop. A fish restaurant right up the street from both of my businesses decided to support me. The restaurant was a chain and very popular. I had flyers printed for my companies, one on each side. They put my flyer in every bag when someone ordered food. Because they supported me so heavily, I ate there at least three times a week. One day, I was in an upscale neighborhood out of town. I was slightly uncomfortable because I felt out of place. I saw the same restaurant as the one in my neighborhood, so I went there since it reminded me of home. I ordered the same exact side dish (broccoli) with my meal. However, I took it back twice because something was wrong. The second time, I had a slight attitude. I told them that the broccoli was hot, and everyone gave me a strange look. But actually, it was meant to be served hot. For years, I only had it from the restaurant in my neighborhood — it was never hot. I had grown so used to that, I had no idea it could be served differently or was being served incorrectly based on the restaurant’s own standards.

View this post on Instagram

Most of our beliefs were given to us; we didn’t create them for ourselves. What we hear other people say influences our beliefs. If our parents say it, if our peers believe it, if our culture embraces it, we most likely will believe it as well. As a result, we have countless beliefs that we are not aware of, and many of these beliefs don’t serve us well. We do not see the damage our beliefs may be causing us because we aren’t even aware of them. Even if we are, we may not know anything else, so we think what we believe is the only way to think.

Creating a New Vision

Youth need exposure and visibility to a world outside of their own to be successful. Why did I keep doing the same things I saw that caused each of my friends to lose their life? Watching people just like me being murdered for doing the same exact things as me — it is the most hurtful and horrifying thing I have ever lived through. I felt hopeless and wanted a better life. I decided it would be better to be dead than to live trapped in poverty for the rest of my life. What was the point of being alive if I was forced to live a life where I was poor, hungry, and never had access to any of the things I wanted? So, why wasn’t losing my freedom enough motivation to change? Prison is only a threat when you feel like you are not already in one. When you are born into a toxic home, in a dangerous community, then forced to live around violence and crime, you are already in a prison. The only difference between hopelessness and a jail cell is one has bars and walls. If someone only knows one way to do something, that is what they are going to do. The odds of someone accomplishing a goal are very low if they cannot clearly see their goal or the route to success, which is why creating a clear vision and a thorough plan is critical. So, what did I need but didn’t have access to that kept me from being able to change my life? My vision was the beginning of my problems.

I saw the world as a negative place, that you have to do whatever it takes to survive and make your way in. What I needed more than anything was a positive vision I could believe in and buy into. A positive vision would have stopped the entire process before it started because all of the negative actions would not have aligned with the positive mindset built around my vision.

Exposure

The next thing I needed was exposure. Exposure reinforces what is possible. Without exposure, youth will believe the only thing that is possible is what they have seen. If they have only seen the world as hard and a place where you have to do anything to survive, that is exactly what our youth will do. If our youth can see a world outside of theirs, a place where people survive without having to commit a crime and are relatively happy, our youth will know they can live that way too.

What I’m not saying, is to take higher risk youth away from their homes. Instead, I’m saying we must show youth a way to live differently, so they can believe there is more and appreciate their interconnectedness and role in a big world. A vision their ancestors had.

In her book, Before the Streetlights Come On, author and environmental activist Heather McTeer Toney, writes about this intersection of the environment and the inner city, where many higher risk Black youth live, due to a history of racism, segregation, and redlining. She says:

In the Black community, we have other things to worry about besides climate change. The idea gets lost in the cloud of issues we muddle through daily. When listed next to job security, food insecurity, gun violence and the blatant racism faced daily by African Americans, climate change ranks low among problems competing for our attention.

But as African Americans, we are disproportionately impacted by the effects of climate change. Black people make up 13% of the US population, but breathe 40% more dirty air than our white counterparts. We live in areas four times as likely to be impacted by hurricanes, tornadoes and floods, and we are twice as likely to be hospitalized or die from climate-related health disparities. Surviving traumatic change is part of our lived history, not new to our experience.

Our history underscores the value of Black people’s role in the climate movement. We know how to adapt to change. I love the example of recycling and reuse. Recycling isn’t a “new” method to reduce plastics and waste in Black households. Enslaved Africans creatively recycled and reused every item they encountered. Our great-grandmothers repurposed leftover materials to create beautiful quilts, patterned with the stories of struggle and survival. They wrapped us in the warmth of their love and legacy. Scraps of meat and vegetables were turned into succulent dishes prepared with care and prayers for nourishment. A plastic bag from the grocery store was also a trash bag, hair conditioner cap, lunch box, Halloween bucket, stuffing for mailing breakable items and what you wrapped the lotion bottle in when traveling so it wouldn’t spill on clothes. For us, recycling and reuse isn’t just to protect the planet. It is a way of life, a nod to our memories, a way to protect what we had and keep what we have. Today, these recycle and reuse lessons remain in our culture regardless of how much money we have. While it wasn’t right, we managed to survive historical climate and environmental injustices while addressing the multitudes of social justice issues plaguing minority and often marginalized people. This is one example of the ways we have naturally responded to climate crisis.

View this post on Instagram

Climate and environmental issues have always been intertwined with our struggles for justice. Trust me, making sure there are equitable climate solutions that speak to the experience of all people is tantamount. Black academics, community leaders and scientists who work in environmental and climate issues don’t get a break from other injustices that impact Black America. Working in climate doesn’t make us immune to the varied injustices that hurt our sons and daughters. After talking about climate change, I go home to concerns of my husband being pulled over by the police or my sweet five-year-old son being categorized as too aggressive when he’s playing. Before giving a speech on environmental justice, I worry that my daughter has to deal with bullying because she’s in a majority-white school and people either pick on her stunning African features or question her Blackness because of her brilliance. The multitude of social justice issues that weigh on Black people never gives way to one or the other, nor to environmental and climate injustice. Despite the myriad of persistent struggles faced by Black American climate advocates, we still press the focus on the environment and climate change. We do this because the science is clear—the climate has changed and continues to do so now. Devastation is taking place as we speak. Time waits for no one. Climate degradation and environmental injustice are deadly factors in Black communities, not unlike killer cops and uncontrolled access to firearms. The difference between mainstream majority-white environmental movements and minority-led Black, brown and Indigenous environmental movements is that the latter does not have the luxury of silo. Our issues coexist.

Our foremothers and forefathers made it the business of the village to ensure that the next generation understood the importance of doing our best to keep everyone safe. Our history serves as a clarion call to environmental consciousness. African Americans have always been molded or influenced by our environment.

Previously in The Revelator:

16 Essential Books About Environmental Justice, Racism and Activism