Picture your favorite winter coat. Something warm and cozy, perfect for bundling up in when the temperature dips. Come January, you reach for it every morning and wouldn’t think of leaving home without it.

Now imagine being forced to wear that coat during a heatwave. For animals that grow a shaggy winter coat in the fall and shed it in the spring, climate change could make that uncomfortable situation a reality.

With climate change already creating new risks for mountain species, researcher Katarzyna Nowak wondered how earlier spring warmings might affect animals that grow and shed heavy coats each year. Earlier this year she launched a project to collect photographs of mountain goats (Oreamnos americanus) taken during their annual molt to track whether or not its timing is changing.

If so, it could create a number of problems for the animals. “If they can’t sync, then their thick winter coats will become a liability in summer,” says Nowak. “They’ll have to seek shade and water and be more active at night, and they could potentially be more vulnerable to predators because of how they’re changing their activity patterns.”

The first key source of data? Members of the public, or “citizen scientists,” who have been invited to share their photos of mountain goats. Nowak turned to the app iNaturalist, which lets users upload photos of plants and animals, including metadata about the date and place where they were observed. Nowak’s iNaturalist project page allows users to contribute their photos for the research.

“It’s just been a really cool way of conducting the project,” she says. “We’ve had some emails from rangers who say, hey, can I hang your mountain goat project poster at the start of this trail, because there’s a mineral lick and people take photos there.” The project has also gotten a boost from the #MountainGoatMoltProject hastag on Twitter.

Checking camera traps at one of our mountain goat study sites in southern #Yukon today went something like this: goat…goat…WOLVERINE! Do a dance in the forest. One for you Justina Ray @WCS_Canada. Beware #mountaingoat kids. #wolverine #MountainGoatMoltProject pic.twitter.com/rGBENf41WQ

— Dr Katarzyna Nowak (@katzyna) July 18, 2018

But recent photos taken by citizen scientists aren’t enough; to track whether molt is changing through time, Nowak needs older photos for comparison. Archived images from Glacier National Park showed plenty of goats, but they didn’t always include the dates the photos were taken, so Nowak’s search for pictures with the necessary dates has led her to some sources she didn’t expect. “We met a reporter from a newspaper near Glacier called Hungry Horse News, and he did a piece about the project and shared some photos with us from the newspaper’s archives, which do have exact dates,” says Nowak. “So it seems like some newspapers — and I never even thought of this initially — may have better-maintained archives than some national parks and even museums when it comes to dating their images.”

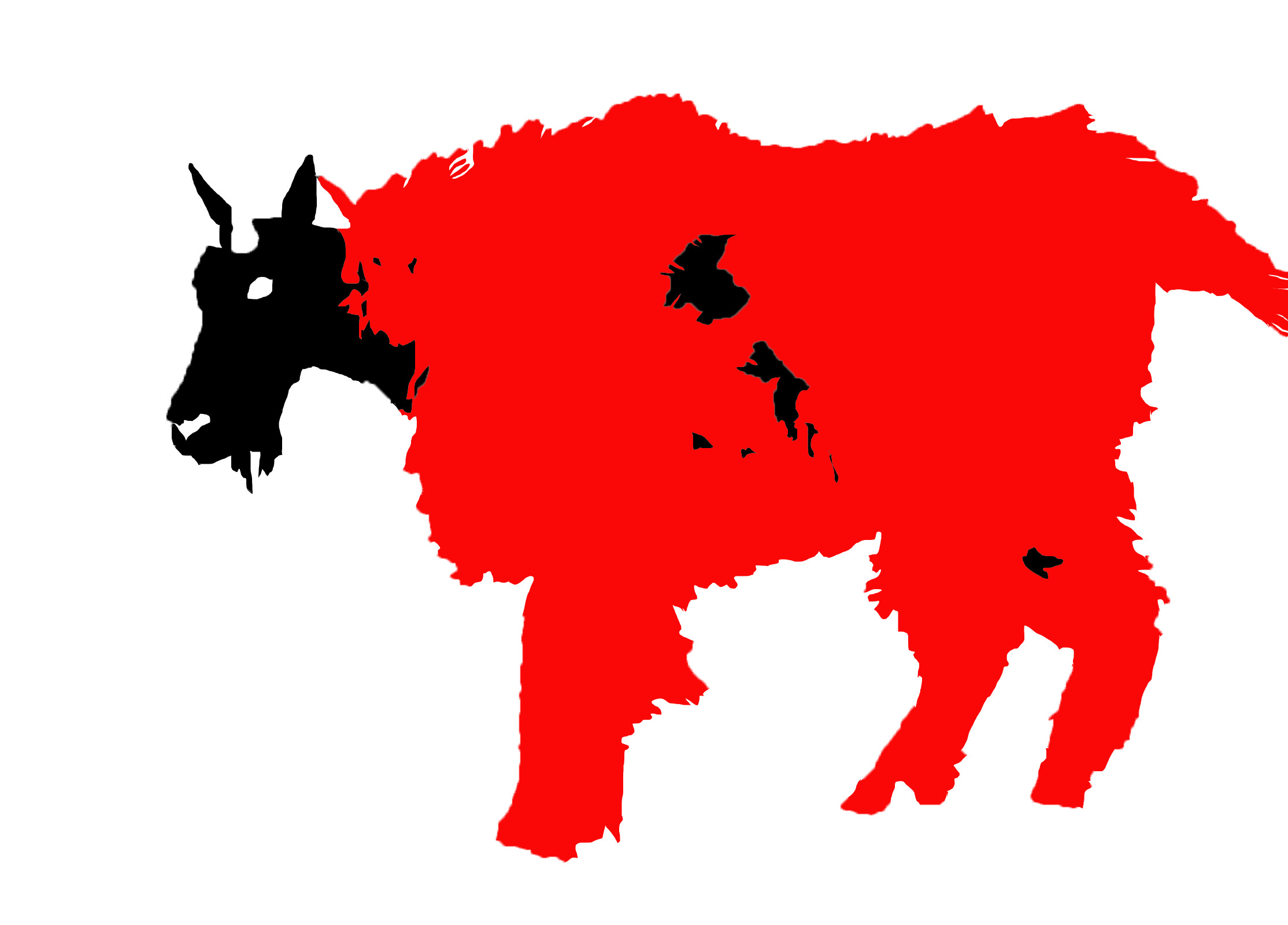

So far Nowak has amassed around 520 photos of molting goats, more than 70 percent of which came from citizen scientists. She also made a trip to the Yukon over the summer to photograph mountain goats at the northern end of their range. She and her colleagues use Photoshop to analyze each individual photo, cropping the animal from the background, painstakingly delineating the shed and unshed portions of its coat, and counting the pixels in each area. They’re currently applying for funding to develop machine learning algorithms that can automate this.

Nowak’s analysis of the photos she has so far hasn’t revealed much evidence about changing molt dates, at least not yet. That could be because she simply doesn’t have enough older photos yet to document long-term changes. She hopes that anyone with mountain goat photos they’re willing to share — especially photos with dates from years or decades ago — will consider uploading them to iNaturalist or the project’s other citizen science portal, CitSci.org.

And while Nowak’s focus is on hooved mammals, climate change’s effects on the timing of plants’ and animals’ annual cycles — what scientists call “phenology” — goes beyond overheated goats.

“Something analogous happens with alpine plants — warmer temperatures can mean earlier snow melt, but because very cold frosts happen earlier, the likelihood of getting your flowers zapped by an early frost increases,” says the University of Washington’s Janneke Hille Ris Lambers, who has studied the effects of climate change on the plant communities of Mount Rainier National Park (home to its own population of mountain goats) for the past decade.

Other animals could be affected, too. Some, such as snowshoe hares, change color with the seasons, turning from brown to white and back again as snow accumulates and then melts. Scientists have started to study how being mismatched with their environment due to earlier spring warming could affect them, with early results indicating they could lose their camouflage from predators during important months when their fur doesn’t match the color of their ground cover.

“I wish people appreciated how large the effects of climate change are going to be on the plants and animals with which we share our planet,” says Hille Ris Lambers. “I think in general folks might assume that warmer temperatures will be good for all kinds of animals — after all, you don’t need that winter coat anymore! — but it’s obviously more complicated than that.”

If it turns out that mountain goats can’t adapt to the shifting timing of the seasons, Nowak and her colleagues have thrown around some fanciful ideas for how to keep the animals from overheating, like providing them with extra shade or even artificial snow. And it isn’t just goats that could be affected — other animals from musk oxen to moose also grow and shed shaggy coats every year, and Nowak hopes more researchers will begin looking at how climate change could disrupt their annual molt cycles.

Nowak believes that thinking about climate change in terms of when you need to take off your winter coat is something everyone can relate to.

“My grandmother in Poland used to wear fur coats, but she doesn’t wear them anymore because it just doesn’t get cold enough to need them,” she says. “Even for people who don’t follow climate science or who have their doubts about our influence on the climate, the fact that your heavy coat has been in the closet for the past five years, that’s something you notice.”

© 2018 Rebecca Heisman. All rights reserved.