The world’s deadliest environmental disaster got its start in 1958. Its effects are still being felt today, more than six decades later.

It wasn’t an oil spill, like the Exxon Valdez or Deepwater Horizon. It wasn’t a chemical disaster, like Union Carbide’s gas leak in Bhopal. And it didn’t have anything to do with nuclear power, like Chernobyl or Three Mile Island.

It happened in the People’s Republic of China in the years after Mao Zedong came to power, causing mass starvation, murder, and even cannibalism.

And it started with a bird.

The Great Sparrow Campaign

In 1958, nine years after the Communist Party of China seized power, Chairman Mao launched what he called the Great Leap Forward, a multipronged effort to transform China into an industrialized nation.

The many changes initiated during this period included banning privately owned farms in favor of collective, state-sponsored agriculture.

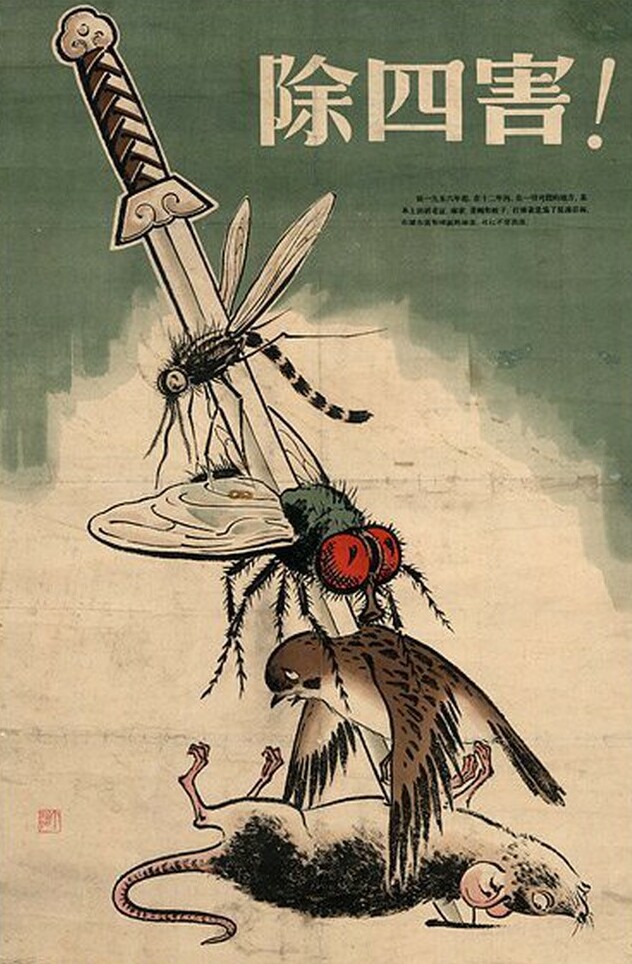

Around the same time, Zedong launched the Four Pests Campaign, an effort to eliminate flies, mosquitoes, rats, and sparrows to improve human hygiene and increase agricultural output. The campaign, accompanied by rampant propaganda, had a powerful slogan: ren ding sheng tian, or “Man must conquer nature.”

Three of those “pests” made relative sense: Flies, mosquitoes and rats can carry disease, and humans still try to control them today. But why were sparrows lumped in with the other three? Mao, it turns out, wanted to prevent the abundant birds from eating grain seeds — a perceived threat to farm production.

To stop sparrows from doing what comes naturally, China directed its citizens to persecute the birds at a level of carnage that may remain unmatched in human history. During the Great Sparrow Campaign people smashed nests and eggs and chased sparrows while shouting, banging pots and spoons, lighting firecrackers, and making other loud noises. Many of the birds spent so much time and energy fleeing the cruel cacophony that they exhausted their reserves and found themselves too tired to escape a well-aimed whack from a shovel. Others “simply dropped from the sky” and expired, as Frank Dikötter wrote in his 2010 book Mao’s Great Famine.

It’s impossible to say exactly how many sparrows died, but many accounts place the toll in the hundreds of millions.

And it wasn’t just sparrows: Birds of adjacent nearby species also fell victim to the noise pollution and violence.

Two years later the absence of sparrows spawned a crisis of epic proportions. Insects such as locusts, previously kept in balance by the sparrows and other birds, swarmed out of control in 1960, a year that — in a grim coincidence — also saw a massive drought. Crops vanished as the voracious insects spread across the country.

As a result of this imbalance in nature, millions of people starved to death over the next two years.

How many? No one knows for sure. The Chinese government officially counts 15 million dead. Chinese journalist Yang Jisheng, writing in his book Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine, put the death toll at 36 million. Some academics suggest even doubling that to 75-78 million.

And they didn’t just die of starvation. People killed each other for food — and committed other unspeakable acts. “Documents report several thousand cases where people ate other people,” Yang told NPR in 2012. “Parents ate their own kids. Kids ate their own parents.”

The ultimate irony: China’s oppressive government had enough grain stored before the disaster to feed everyone in the country. However, they refused to release it and covered up the problem (in part by arresting and beating anyone who questioned the official narrative).

Today China still fails to acknowledge the problem of its own making, calling it the “Three Years of Difficult Period.”

Regardless of what you call it, the Great Sparrow Campaign and resulting environmental disaster offer six major lessons for the future.

Lesson 1: Environmental Disasters Last a Long Time

The Chinese famine was over by 1962 — but for those who survived, it’s hardly a thing of the past.

Two studies published in 2023 examined the lifelong health effects of starvation resulting from the Great Sparrow Campaign. Researchers found that the survivors, many now in their eighties, and the people born shortly after the famine all suffered health problems, or “noncommunicable diseases,” at a significantly higher rate than the general population. These include “hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, cancer, lung disease, liver disease, heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, digestive disease, psychiatric problems, memory-related disease, arthritis, and asthma,” according to one of the studies.

As the authors of the study in the journal BMC Public Health wrote, “Experiencing famine at an early age or the experience of famine in a close relative’s generation (births after the onset of famine) are associated with an increased risk of” these noncommunicable diseases.

The second study, in the journal PLOS Global Public Health, found that the lifelong effects were particularly prevalent in people whose mothers were pregnant during the famine.

We can see parallels of this today in modern famine crises such as the ones happening right now in Gaza, Sudan, and Yemen, which many experts warn will cause suffering for years if not decades to come.

Neither study examined the mental-health effects of the famine, but “there are certainly social and psychological effects of these kinds of repressions,” says historian Ruth Ben-Ghiat, author of the book Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present, who frequently writes about authoritarianism. Previous research, she points out, has shown intergenerational traumas in descendants of the Holocaust, slavery, war, and genocide.

Lesson 2: Science Matters

Authoritarians have a pattern: They belittle, ignore, diminish, and even punish scientific expertise.

That pattern played out in China’s great famine. As Judith Shapiro wrote in her 2001 book Mao’s War Against Nature, the Chinese leader held disregard for science throughout his rule. Even before the crisis, his agricultural policies had caused mass deforestation and hydrological problems. Mao even sent one hydro engineer to a labor camp for criticizing his plans.

And he ignored scientific warnings about removing sparrows, which led directly to millions of deaths.

His anti-science policies were not restricted to the Four Pest Campaign. Just a few years later, during the 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution, Mao ordered farmers to plant grain instead of the local crop species they’d grown for generations, even in areas inhospitable to grain. “Such formalism supplanted local practices and wisdom, damaged the natural world, and inflicted enormous hardship on the Chinese people,” Shapiro wrote.

We see this pattern repeating today in authoritarian regimes around the world, which routinely denigrate the science of climate change in favor of extractive technologies.

Lesson 3: Compounding Problems Make Things Worse

China’s famine wouldn’t have occurred if not for Chairman Mao’s leadership, but when it did arrive, it was made worse by drought.

That’s a portent of things to come.

A study published earlier this year found that 2024 was already the worst year on record where water scarcity, severe drought, flooding, and other effects of extreme climate change had served as a linchpin of armed conflict. The study also found that these acts of violence have increased from about 20 incidents a year in 2000 to 347 as of its release on Aug. 22.

As climate scientist Peter Gleick, an author of the study, said in a press release, “the significant upswing in violence over water resources reflects continuing disputes over control and access to scarce water resources, the importance of water for modern society, growing pressures on water due to population growth and extreme climate change, and ongoing attacks on water systems where war and violence are widespread, especially in the Middle East and Ukraine.”

Many of these conflicts are caused by authoritarian regimes, but as Ben-Ghiat explains it, a crisis also create opportunities for strongmen and their corporate, billionaire allies to seize power and exploit the planet.

“The core of authoritarianism is fewer rights for the many,” she says, “and more liberties for the few, meaning the elites, the people who make money off plundering the environment. Control of resources, control of land — it’s bringing out the worst. You see that more as resources become scarce. A lot of the conflicts in the Middle East are about controlling water. I see right now as the last gasp of these plundering evil people. It’s getting worse because they’re all out trying to plunder as much as they can.”

Lesson 4: Authoritarian Rule Is Deadly (Especially for Protestors)

Ben-Ghiat thinks the Chinese famine was so extreme that it’s an outlier when it comes to the history of authoritarianism, but it still contains parallels to other regimes, including the denigration of science, the reliance on propaganda, and the crushing of resistance.

That’s not just history. Even today hundreds of environmental activists and defenders are killed every year, according to data compiled by the organization Global Witness.

“The most dangerous type of protestor to be is an environmental protestor,” says Ben-Ghiat.

Meanwhile the very nature of strongman governments makes it easier to commit the types of environmental crimes people are protesting.

“When you have dictatorship, you can orchestrate campaigns like the Great Sparrow Campaign or the famine created by Stalin very efficiently,” says Ben-Ghiat, “because you there’s no one telling you not to. There’s absolutely no opposition in parliament, there’s no journalism, there’s no free press. You’re not responsible to anyone. You’re not going to lose your job or get voted out because you cause these effects.”

Democracies are not immune from these problems, she points out, “but in authoritarian states, it’s all very nakedly revealed because there’s no check on the government.”

Lesson 5: Given Time and Effort, Some Things Recover

The bird targeted by Mao was the Eurasian tree sparrow (Passer montanus) — by 1962, they were all but extinct in China.

But the Eurasian tree sparrow is a wide-ranging species. When China realized its countryside needed the birds, it brought some back. Many books and studies report that China imported thousands of sparrows from neighboring Russia to reestablish some balance in devastated ecosystems.

It’s worth noting that in the years I’ve been studying and writing about the Chinese famine, I’ve never uncovered any primary documents about these Russian sparrows. Nonetheless, the species today flies in Chinese skies where they were once erased: There are thousands of observations from China on the citizen-science site iNaturalist. The sparrow also ranges from the easternmost coasts of Europe to the westernmost coasts of Asia and beyond into many island nations. Less populous than before, they’ve faced recent declines due to agriculture and other development but still number in the hundreds of millions — not bad, considering how many were wiped out six decades ago.

Lesson 6: We Need to Talk About These Things

Harvard University granted Yang Jisheng a prestigious Neiman Fellowship for his book Tombstone in 2016. The retired journalist was forbidden from traveling to the United States from China to receive the award, and his book remains banned in the country of his birth. The subject of the famine remains taboo in China to this day.

That’s exactly why we need to talk about it — and other environmental crimes being committed around the world — even if corporations or governments threaten to punish us for telling the truth.

As Timothy Snyder writes in his essential book On Tyranny, “To abandon facts is to abandon freedom.”

Authoritarians want their abuses and deadly histories to fade from view. It may not be comfortable to address our painful pasts or dangerous present, but to ignore unpleasant realities is an invitation to catastrophe.

Previously in The Revelator:

Portugal’s Deadly Wildfires Are Rooted in Its Authoritarian Past