By Sam Williams, Durham University; Lourens Swanepoel, University of Venda, and Steven Belmain, University of Greenwich

Across the globe, the numbers of carnivore species such as leopards, dingoes, and spectacled bears are rapidly declining. The areas they occupy are also getting smaller each year. This is a problem, because carnivores are incredibly important to ecosystems as they may provide services such as biodiversity enhancement, disease regulation, and improving carbon storage. And that, in turn, is important to human wellbeing.

But convincing people to conserve wildlife based on these indirect benefits can be challenging – particularly in the case of farmers. After all, carnivores such as leopards can pose a threat to livestock, livelihoods, and sometimes even lives. So interactions between farmers and carnivores have typically been framed as a conflict.

Farmers often overestimate these threats. For many, the response is to kill carnivores – even those that are not eating livestock. This is one of the main reasons why carnivores are in crisis.

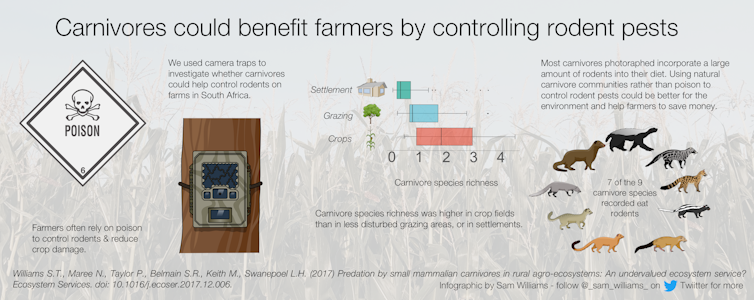

This could change if people were aware of the more tangible benefits that carnivores could provide. Our new study showed that far from causing problems for farmers, carnivores could actually be beneficial by controlling rodent pests.

Rodents and carnivores

There’s a desperate need for farmers to control rodents because they destroy 15% of the crops growing in African fields. The most common solution is to use poison. But this can be expensive and can kill many other species. On top of this, rodents eventually become resistant.

We set out to find out whether carnivores that eat rodents were found naturally on smallholder farms. We set camera traps on land used for cropping in South Africa, areas used to graze cattle (which was less disturbed than cropland), and among houses in village settlements.

So not only are carnivores present on farmers’ fields, but it’s likely that they are also controlling rodents that would otherwise damage crops. But more research is needed to confirm this.

Big potential

The idea to use natural predation to control rodents is not new. But to use mammalian predators to assist in biological control of rodent pests has often been neglected in conservation circles. As such there is great potential for carnivores to help farmers, but for this to work, farmers would need to stop killing them.

Changing these perceptions would take a lot of work. But efforts to change African perceptions about predatory birds, particularly barn owls, have been successful in some South African townships. Successful approaches to change community attitudes has often relied on education programmes through local schools. Bringing owls, snakes and other predators to primary schools can help raise awareness among children, who then go home and educate their parents, ultimately breaking down widely held superstitions.

If education campaigns could convince farmers to kill fewer carnivores, carnivores might just repay the favour by doing a better job of controlling rodents in crop fields. This could lead to less reliance on poisons, avoiding unnecessary killings and costs.

If successful, this could help farmers to save money, while working in a much more environmentally friendly way. This really could be a win-win situation for both people and wildlife, and it shows that interactions between people and carnivores on farmland can be much more nuanced and positive than the traditional image of conflict.

Finding new ways in which people and wildlife can coexist will be essential to lessen the impact of the growing human population on the ecosystems on which humans depend.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Previously in The Revelator:

The Surprising Ways Tigers Benefit Farmers and Livestock Owners