Every day drivers head north on Route 205 out of Portland, Oregon, cross the mighty Columbia River and the state line, and arrive in Washington.

Many of them will immediately head east, where on a clear day they’ll soon see snow-capped Mt. Hood looming over Highway 14. Also known as the Lewis & Clark Highway, this busy road will take them toward the suburban cities of Camas and Washougal.

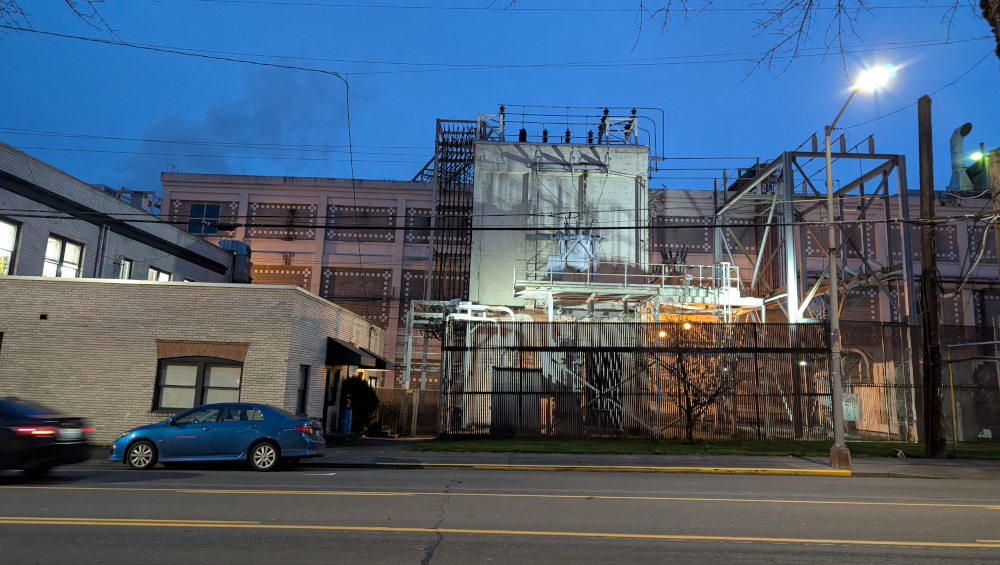

But as they arrive in Camas and cross a narrow bridge, something else will loom over the scenic view: an enormous paper mill on the river’s edge.

That paper mill, which at one point processed hundreds of tons a day, has been a defining element of Camas for more than a century. The town grew up around it. Residents walked down the hill to work there and sent their kids up the hill to go to school, where the local basketball team is still called the Papermakers (complete with a mascot, the Mean Machine, that looks like an anthropomorphic paper press).

Today the mill, now owned by Koch Industries, is a shadow of its former self. Relatively few people still work there. Much of the 660-acre property lies fallow.

But its legacy lives on — in the history and pride of Camas, in the minds of its residents, and in the soil and water, which many people worry carry the burden of generations of pollution.

And although few realize it, the paper mill’s legacy also exists on the national stage.

In many ways it inspired the first Earth Day.

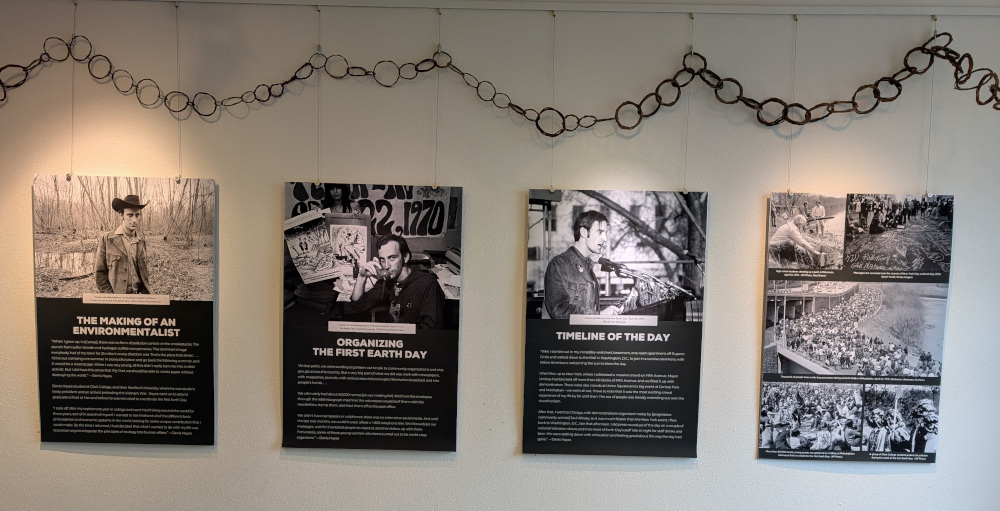

Famed environmental advocate Denis Hayes coordinated the first national Earth Day in 1970. He later founded the Earth Day Network and became a leader in solar power and energy policy.

But before that he grew up in Camas, which at the time had an occasionally noxious reputation.

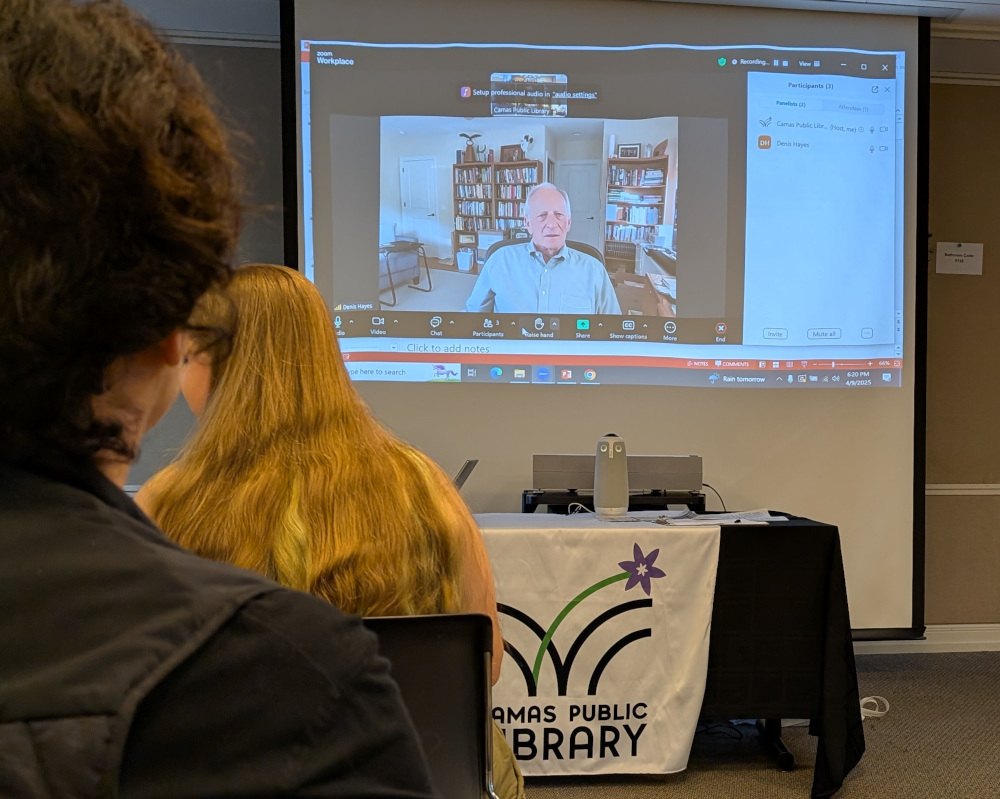

“If you talked to someone in Portland and mentioned Camas, universally the response was, ‘Oh yeah, that’s where the stink comes from,’ ” Hayes, now 80, recalled during a recent Zoom presentation to an in-person audience at the Camas Public Library. “The whole region was known for the stink of this uncontrolled paper mill.”

The stink came from “vast quantities of uncontrolled sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sulfide” emitted by the mill. Those pollutants came back down in the form of acid rain — and as Hayes noted, it rains quite a bit in the Pacific Northwest.

The effect was immediately visible in town, where the roofs of cars corroded under the acidic onslaught.

“People began to ask, well, if it’s doing that to my car, what’s it doing to me,” Hayes said. “The answer, with regards to the automobiles, was that instead of reducing the pollution, they put a shower at the end of the parking lot” to rinse cars before they drove home.

Wildlife was affected, too. “Every now and then you’d go down to the Columbia River slough and find scores of dead fish, in some cases hundreds of dead fish, just floating there,” Hayes said.

Camas had its good sides, of course. “What I did have growing up was the ability to walk through some of the most magnificent forests on Earth and to ride my bicycle down through the Columbia River Gorge and the spectacular scenery,” Hayes recalled.

But even there the paper mill took a toll.

“You’d go out in the forest and go hiking in the summer, in these astonishingly beautiful Douglas fir forests, and then two years later you go back there and it is almost clearcut. There was this catastrophic approach to clearing out natural resources.”

The beauty and the destruction “came together and sort of made me think, not too profoundly, that it must be possible to make paper without destroying the planet,” he said.

Camas was just one of Hayes’ influences, and Hayes was one of many people behind the first Earth Day and the environmental successes that followed.

But what followed remains significant.

“The context then was one where we were pretty highly motivated to try to get some kinds of regulations someplace,” Hayes recalled. “This is not a personal accomplishment. There were a huge number of things that were involved in this, including the presidential aspirations of a senator named Ed Muskie.”

After the first Earth Day, the organizers — who had formed a nonprofit called Environmental Action — launched what they called “the Dirty Dozen” campaign targeting congressional representatives with bad records on environmental issues. “We tried to take out several of the worst members of Congress, and we successfully defeated seven of 12 incumbents,” Hayes said. “It is really, really hard to beat an incumbent member of Congress. And we managed to take out seven of 12. And it was clear that we were the margin of a victory in each of those cases.”

Among the defeated politicians was Rep. George Fallon. “At that time Fallon was the chairman of the House Public Works Committee. If you wanted to have a federal building, you wanted to have a prison, a courthouse, a dam, any kind of public work in your district anywhere across the country, you had to have the permission of the guy who chaired that committee. When we took out George Fallon, clearly with an environmental campaign, that absolutely transformed the House of Representatives.”

One month after that election, Muskie helped introduce what would become the Clean Air Act. “And the Clean Air Act passed the Senate on a voice vote and passed the House of Representatives 434 to 1. There was one member of both Houses of the American Congress that voted against the Clean Air Act. Something that would have been inconceivable in 1969 became unstoppable in 1970,” Hayes said.

“Those are the kinds of magic moments that can happen in a democracy where everything, just like a school of fish is going in this direction and suddenly it goes in a different direction,” he continued. “It was my thrill to have been part of a handful of those occasions.”

A new generation of Camas residents — in fact, multiple generations — has taken the lesson of the first Earth Day to heart.

Several residents recently came together to form the Camas Earth Day Society, which organized Hayes’ talk at the local library and is working toward a sustainable future in their home town. They’ve worked with local students, many of whom asked Hayes questions during the event. The organization has also held an art show, organized a native pollinator display, and raised awareness of clean air and water issues in Camas.

They have ambitious dreams that boil down to a simple truth, both in Camas and around the world: Everyone can make a difference.

Fifty-five years after the first Earth Day, the future of environmental protection has darkened once again. The Trump administration has enabled corporate polluters, slashed climate programs and budgets, and seeks to slash and burn practically all environmental regulations.

But the crowd that gathered earlier this month at the Camas library — people young and old — came together despite those threats, ready to talk about solar power, protecting native plants, improving water quality, reducing pollution, and mobilizing for the future.

More than one T-shirt that night read “Earth Day Is Every Day” — a sign that the seeds of that first day continue to sprout.

Previously in The Revelator:

Comics for Earth: Eight New Graphic Novels About Saving the Planet and Celebrating Wildlife