We’ve spent a century in the United States feverishly building more than 79,000 dams. Two decades ago we started to undo some of that, dismantling nearly 1,000 dams, many aging and unsafe, and restoring the rivers they had impoverished.

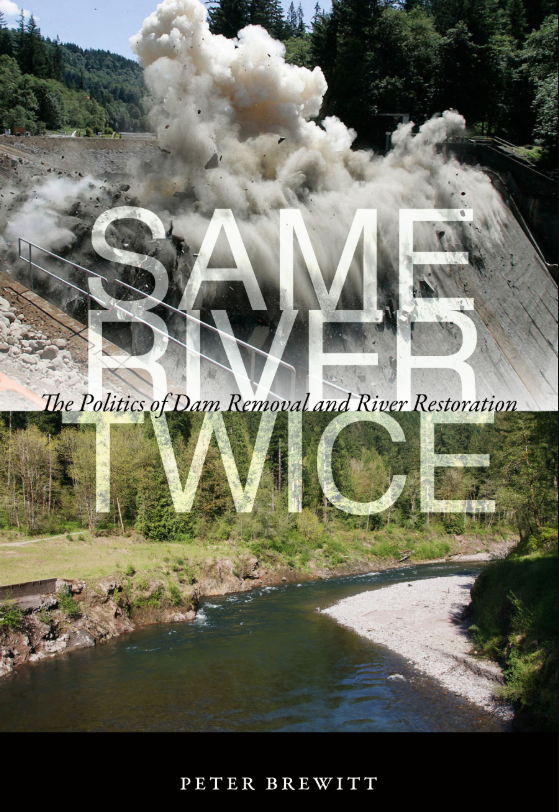

Despite this uptick in dam removal, there’s no blueprint for how it happens — the politics, engineering and ecology are unique to each case. Still, our experience so far can help guide future dam-removal projects. That’s the premise behind a new book, Same River Twice: The Politics of Dam Removal and River Restoration, by Peter Brewitt.

Brewitt, an assistant professor of environmental studies at Wofford College, takes a close look at three dam-removal projects in the Pacific Northwest, digging into the political, social, regulatory and scientific aspects of removal. His three historic case studies are relevant to communities across the country.

The first case study examines two dams on the Elwha River in Washington, which runs through Olympic National Park to the Strait of Juan de Fuca in the Pacific Ocean. The dams meant different things to different people: The downstream community of Port Angeles saw the dams as “places where human ingenuity had improved nature,” Brewitt writes. But environmentalists and members of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe saw the devastating impact the dams had on native salmon runs and how they blocked restoration of one of the wildest rivers in the country.

Motivated by ecological and cultural concerns, removal efforts began gaining momentum in the mid-80s. By 1992 the Elwha Act, a piece of federal legislation aimed at river restoration and dam removal, was passed. But the actual removals would still take nearly two decades to achieve. Efforts were delayed by a vocal local opposition group and funding problems.

As Brewitt details, dam removals are not immune to the politics of the day, and efforts to take down the Elwha dams in the 1990s coincided with the Pacific Northwest’s bitter “spotted owl wars,” which pitted environmentalists and loggers against each other.

Even though the dam issue had nothing to do with logging or owls, “Environmental advocates who’d been trying to remove the Elwha dams found themselves facing hardened opposition that reflexively hated them,” he writes.

Despite this local culture war, the 105-foot-tall Elwha Dam and 210-foot Glines Canyon Dam finally came down in 2011 and 2014, making it the largest dam removal project in the country.

A similar situation played out in Grants Pass, Oregon, with Savage Rapids Dam, an aging structure that proved deadly to Rogue River salmon. The dam’s owner, Grants Pass Irrigation District, agreed to remove the dam in the mid-90s but faced enormous pushback from the public that delayed the project.

“The removal of Savage Rapids Dam destroyed no jobs, bankrupted no businesses, released no toxins,” writes Brewitt. “The dam’s function, to divert the waters of the Rogue River into GPID’s canals, continued as before — the district, using pumps, delivered the same amount of water to its patrons. But hundreds of people had fought furiously, for years, risking their bank accounts, their reputations, even their friendships in the process.”

A local coalition felt invested in the scenic and recreational values provided by the dam and its impoundment, Savage Rapids Lake. Controversy over the dam was enmeshed in the same growing anti-government and anti-environment sentiment that plagued the Elwha effort: In striking echoes of the modern Trump era, dam savers labeled their opposition “Nazis” or environmental terrorists, rebuffed scientific reports, and conflated dam preservation with somehow helping to “save America,” Brewitt explains. Many stoked fears that the removal of this dam would lead to the removal of other key dams in the region including on the Snake and Klamath rivers.

At the basic heart of the issue was a clash of values and beliefs. In the end, coalition building overcame ideological clashes, propelled by a federal judge ordering the stakeholders into mediation rather than issuing a decision that might further inflame conflict. The dam finally fell in 2009.

But not all dam removals are so contentious.

The situation with the Marmot Dam, part of the Bull Run Hydroelectric Project, on the Sandy River not far from Portland, Oregon played out differently, writes Brewitt. The dam, which at one time powered Portland’s trolley system, was owned by Portland General Electric. By the early 2000s the project produced only 1 percent of the region’s energy and was a growing economic liability as environmental regulation increased. The company made the decision to decommission the hydro project in 1999 and planned to remove Marmot Dam and the nearby smaller Little Sandy Dam shortly after.

Public concern slowed the removal, particularly local residents’ attachment to a recreational lake created by the power project, concern about how draining it might impact groundwater and the ecological impacts the released silt would have on the river. But the opposition never reached the antagonistic levels seen in Grants Pass and Port Angeles.

Marmot dam came down in 2007, and Brewitt credits the relatively short time span of the process — less than a decade from inception to removal — to the fact that the biggest obstacle wasn’t if the dam should be removed, but how. The paramount concern was how to protect wild populations of salmon from hatchery-raised stock that had been blocked from the upper reaches of the river by the dam.

While these three dam-removal projects took place in the Pacific Northwest, Brewitt contends that similar stories could also be written about dam removal on the East Coast or the Great Lakes. And by studying the detailed history of these cases, we can glean some larger points that apply elsewhere in the country or the world. Here are a few:

- Dams that are of little economic value will continue to make good candidates for removal, but a source of contention will remain over who should claim financial responsibility.

- Science is useful and necessary, and we need more of it — particularly in understanding how river ecology changes in the months and years following dam removal. But not everyone willingly accepts scientific reports if it doesn’t fit their point of view. So science alone won’t resolve all conflicts.

- Culture plays a big role. Dams become monuments to communities, impoundments are seen as natural features on the landscape even though they’re far from it, and “beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and as such is not subject to negotiation,” Brewitt writes.

- Mega-coalitions must be formed in order to garner enough public and political support and raise the necessary funds.

- Ecological restoration is good for the economy, and it now employs more people than logging or coal mining.

All this means we’re likely to see more dam removals in the future.

“As national values and regional economies shift and scientific knowledge develops, ecological restoration is becoming a nationwide political priority,” Brewitt concludes.

We need more books like Same River Twice to examine what works, what doesn’t, and what we can learn from our efforts.

![]()