Part I of The Revelator’s “A Border Betrayed” investigation.

IMPERIAL BEACH, Calif.— U.S. Border Patrol Agent Christopher Harris steers his truck along the hilly road next to the border fence separating this beach community in the extreme southwest corner of the U.S. from Tijuana, Baja California’s largest city.

On a late November afternoon, Harris tours three different canyons along the border. At the bottom of each canyon, a ribbon of dark wastewater originates in Tijuana and flows into the wetlands of the Tijuana Slough National Wildlife Refuge on its way to the Pacific Ocean.

No one in the United States is certain whether the effluent is coming from Tijuana’s failing wastewater-treatment system or if it is illegally dumped in the canyon creek beds in Tijuana. On this day, it flowed through dry creek beds, where Harris says it hadn’t rained in many weeks.

The saltwater estuary has long been a hotspot for drug smuggling and human trafficking. Harris says Border Patrol agents conducting patrols and apprehensions of illegal immigrants are routinely exposed to contaminated mud and effluent. Harris, the secretary for the National Border Patrol Council Local 1613, says more than 80 agents have suffered from contamination, injuries and illnesses — including encountering chemicals that sometimes eat right through their boots.

Harris holds up a pair of fairly new work boots and says they belong to an agent who suffered chemical burns on his feet after the rubber soles were melted by chemicals in the effluent.

“We’re breathing it in,” Harris says. “It gets in your mouth, you’re ingesting it. It gets in your mucous membranes. We’ve had people with what they believe is methane burns to the lungs.”

During heavy rains there’s no doubt that Tijuana’s wastewater-treatment system routinely fails, sending hundreds of millions of gallons of raw sewage flowing into the Tijuana River from Mexico and then into the U.S. The floods of sewage force health officials to close public beaches on Imperial Beach — where 25 percent of the population lives below the poverty line and 60 percent are nonwhite — and sometimes further north, toward the Silver Strand State Beach and ritzy Coronado.

Even when there’s no heavy rain, 40 million gallons a day of treated — but mostly raw — sewage is dumped into the Pacific Ocean from Tijuana’s sewage treatment plant, located less than five miles south of the border, says Imperial Beach Mayor Serge Dedina.

The sewage can drift north during southern swells, forcing U.S. public beaches to close. Dedina has led a crusade to try to get desperately needed funds to help Tijuana make emergency repairs to fix collapsing sewer lines and failing pump stations and upgrade its primary wastewater-treatment plant.

An avid surfer, Dedina has repeatedly fallen ill after surfing off Imperial Beach. He says there have been more than 320 sewage spills in the past two years. “It’s like a horror show,” he says during an interview on a picnic bench overlooking the beach. “It’s horrendous.”

The serious health problems and environmental contamination are not isolated to Tijuana. The lack of adequate wastewater treatment occurs all along the 1,954-mile U.S.- Mexico border, and the problems don’t just originate in Mexico.

A three-month-long investigation by The Revelator reveals thousands of underserved communities on the U.S. side of the border that lack basic environmental and health infrastructure such as sanitary sewer systems and utility-provided drinking water. Most of the people living in these unplanned communities, called colonias, are poor and of primarily Hispanic descent. Environmental infrastructure problems also afflict several larger U.S. cities, including Nogales, Ariz., Calexico, Calif., and Laredo and El Paso, Texas.

While so much of the discussion in Washington, D.C., revolves around Trump’s proposed $25 billion border wall, a longstanding humanitarian crisis is going unaddressed along the nation’s southern border — home to some 14 million people.

The Revelator traveled to some of the hardest-hit communities in California, Arizona, Texas and in Mexico and spoke with residents, politicians, health workers and others living among a failing and largely forgotten infrastructure system. We found poverty, sickness and environmental contamination plaguing both large and small communities straddling the U.S.-Mexico border — a region that experiences poverty rates double the national averages and has some of the highest rates of infectious disease in the United States.

In the coming months, our “Border Betrayed” series will take readers to those border communities and examine the profound health and environmental effects of a region whose infrastructure has been systematically neglected by both countries — leaving millions of people to suffer the consequences far from the view of politicians and most of America.

In the coming months, our “Border Betrayed” series will take readers to those border communities and examine the profound health and environmental effects of a region whose infrastructure has been systematically neglected by both countries — leaving millions of people to suffer the consequences far from the view of politicians and most of America.

Investing in Mexico Helps Americans

To understand the crisis is to understand its roots in money, power and political decisions.

Since the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994, the United States and Mexico together have invested more than $10 billion in constructing an international network of wastewater treatment plants, potable water connections, modern landfills, hazardous waste collection sites, recycling centers and renewable energy facilities that benefit the citizens of both countries.

But the money has been nowhere near enough to stem the rising tide of environmental health problems afflicting both sides of the border.

The outlook is even worse.

President Trump’s proposed $25 billion border wall comes at the same time his administration wants to eliminate funding for the most important Environmental Protection Agency grant program used to construct environmental infrastructure along the U.S.-Mexico border including Tijuana.

The administration also opposes an increase in funding for the North American Development Bank, which provides infrastructure development loans to border communities in the United States and Mexico. Without additional capital, the bank’s ability to make loans will be sharply reduced.

Trump’s anti-Mexican statements further inflame relations between the countries and come at a time when Mexico is recovering from two major earthquakes that require significant public investment, reducing money for border projects.

“The rhetoric is bad and the policy is zero,” Dedina says of Trump’s statements and the administration’s recommendations for spending on border environmental infrastructure. “They have made it really very clear how they feel.”

Concentrating on hot-button issues of immigration ignores the basic human-rights problems that affect citizens in both countries.

“The Trump administration, with all of its hyperbolic rhetoric, has so obscured and clouded the issue that people aren’t thinking straight,” says Steve Mumme, a professor of political science at Colorado State University, where he specializes in comparative environmental politics and policy with an emphasis on Mexican government and U.S.-Mexican relations.

“They are suddenly retreating to their corners of the ring and thinking that they don’t have to engage anymore and the problems will somehow magically solve themselves and people will go away,” he says. “Good luck with that.”

The Trump administration is clearly aware of the acute sewage contamination issues in Imperial Beach. Dedina says he met with EPA Director Scott Pruitt’s senior adviser, Ken Wagner, last fall and discussed the issue. Nothing tangible resulted from their meeting, Dedina says.

Diverting billions of dollars for the wall while at the same time slashing funds to invest in environmental infrastructure — such us helping to finance improvements to Tijuana’s wastewater treatment system — ultimately hurts Americans, border experts say.

“Investing on the Mexican side of the border really improves the quality of life for U.S. residents,” says Paul Ganster, chairman of the Good Neighbor Environmental Board, a federal advisory committee that makes recommendations to Congress and the White House on environmental infrastructure needs on the U.S.-Mexican border.

“It’s absolutely clear,” says Ganster, who is a social scientist at San Diego State University specializing in Latin America. “There is no doubt about it.”

America’s Forgotten People

The environmental health crisis stalking millions of people living on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border has been steadily unfolding for decades but has become more acute in the past 20 years as the population along the border continues to surge.

In a strange twist, it is the American side of the border that is substantially poorer when compared to the rest of the United States. Meanwhile, the Mexican border cities are relatively well developed compared to many areas of their country, where basic services like electricity, running water, paved roads and sanitary sewers can be extremely limited or nonexistent.

“The border region tends to be the poorest area in the United States,” says Ganster. “And at the same time, across the border in Mexico, is an area where there has been explosive demographic growth and urbanization and manufacturing development.”

The Mexican border cities, for the most part, are much larger than their U.S. neighbors. In addition to NAFTA, which greatly increased trade between the two countries, Mexico and the United States have passed laws that encourage U.S. companies to build factories in Mexican border towns. The factories, called maquiladoras, import parts from the U.S. and assemble products in Mexico, taking advantage of $2 an-hour wages. The finished goods are then re-exported back into the United States at reduced tariffs.

Trade and manufacturing have attracted millions of Mexican workers and families to border communities. There were approximately 6,171 maquiladoras employing 2.5 million workers in 2014, according the University of Arizona’s Economic and Business Research Center. The mass migration of workers to fill these jobs has overwhelmed the ability of Mexican border cities to keep up with basic services.

Mexico is still a developing nation, and its border cities have relatively small amounts of per capita income to pay for basic services. Mexican border cities have focused primarily on providing electricity and potable water at the expense of other systems that people in the United States might take for granted, Ganster says.

“Sewage has not been the highest priority,” he says.

This allocation of limited resources has a direct impact on the United States. Mexican border cities — including Tijuana, Mexicali and Nogales — are upstream from their U.S. neighbors. So when the overwhelmed wastewater system in Tijuana fails, public beaches close in Imperial Beach and border agents get sick. When Mexicali’s sewage system collapses, the New River is polluted as it flows north to the Salton Sea in California. And when the Nogales, Sonora wastewater and storm water systems can’t handle heavy flows, the Santa Cruz River valley in Arizona is contaminated.

Farther east in Texas, there’s no escaping the serious health impacts of millions of gallons of raw sewage being dumped every day into the Rio Grande, regardless of which flag flies over your border town.

Border cities in both nations draw their drinking water from the river. In some cases, like in Nuevo Laredo, located just across the Rio Grande from its namesake in Texas, the city’s drinking water intake sits within a quarter-mile downstream of two untreated sewage outfalls.

None of these problems are new.

They have persisted for generations and will continue as more people move to towns and cities located adjacent to the border that simply don’t have sufficient resources to provide basic environmental infrastructure.

About 14 million people live in 38 Mexican municipalities and 23 U.S. counties adjacent to the border. The population in these municipalities and counties is expected to more than double to 29 million by 2045, according to a 2013 comprehensive analysis of the U.S.-Mexican border by the Border Research Project.

More people means more needs for basic sanitary services, including sewage treatment plants, sanitary landfills, potable water connections, toxic waste management, renewable energy, clean vehicles and road paving to reduce dangerous levels of air pollution that engulfs border communities.

The North American Development Bank, which is owned and jointly operated by the United States and Mexico, estimates that $10 billion is needed just to provide first-time connections for wastewater and/or potable water for communities on both sides of the border, with $8.5 billion just in the United States.

And that doesn’t include upgrading collapsing sewer lines and modernizing sewer treatment facilities. Officials estimate that Tijuana alone will need $400 million to overhaul its crumbling wastewater treatment system.

These environmental health problems have been brewing for decades.

Twenty-five years ago the Sierra Club estimated that $20 billion was needed for basic environmental infrastructure along the border — and that was before NAFTA went into effect.

“There certainly is a higher cost now given that NAFTA included incentives for corporations to shift their pollution to border communities,” says Ben Beachy, director of the Sierra Club’s Responsible Trade Program.

The World’s First Green Bank

Obscured in the raging debate over President Trump’s proposed border wall and the ongoing contentious negotiations over whether the United States will withdraw from NAFTA is another crucial trilateral initiative between the United States, Mexico and Canada that created the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation.

During the NAFTA debate in the early 1990s, Congress, environmental groups and other nongovernmental organizations demanded that the trade agreement include environmental and labor protections to address the already serious environmental problems along the U.S.-Mexican border that most agreed were only going to get worse with increased trade.

The environmental cooperation agreement was created to address the ongoing environmental disaster, making NAFTA the first trade agreement that explicitly linked trade to environmental protection.

When NAFTA went into effect on Jan. 1, 1994, only 21 percent of wastewater in Mexican border cities was being treated, causing widespread pollution in shared watersheds including the Tijuana River, the Colorado River, the New River, the Santa Cruz River and the Rio Grande. That number is now close to 90 percent.

In addition to the environmental cooperation agreement, the United States and Mexico also established the Border Environmental Cooperation Commission and the North American Development Bank, widely considered the world’s first “green bank,” to help Mexican and American border communities finance the construction of wastewater and potable drinking-water projects.

Mexico and United States each contributed $225 million to provide capital for the development bank to make loans and each pledged an additional $1.3 billion in callable capital reserves. The bank’s charter created a board of directors with an equal number of representatives from each country.

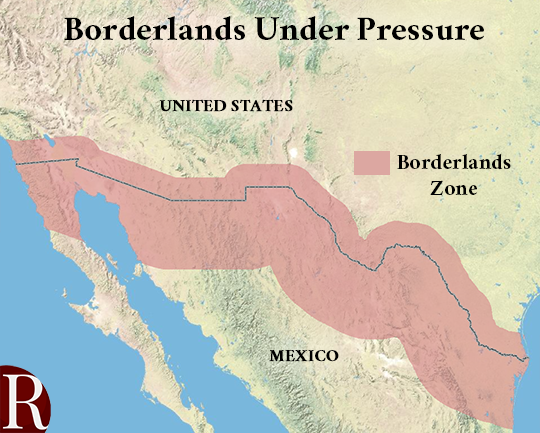

Today the bank provides environmental infrastructure loans within the borderlands region that straddles both sides of the border. The borderlands includes the area from 62 miles (100 kilometers) north of the border to 186 miles (300 kilometers) south and stretches from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico.

The bank’s lending has expanded to include wind farms and solar energy to reduce border air pollution and desalinization plants in Mexico to reduce reliance on declining groundwater supplies and over-allocated surface water.

Mexico supports doubling the bank’s capitalization, which would allow it to increase annual lending to $350 million by 2024, but the United States has not yet agreed. Without additional capital, the bank’s projected annual lending will drop from $250 million to below $90 million, the Treasury Department stated in 2017.

“Strengthening [the development bank] would be tangible demonstration of the United States commitment with Mexico to build a stable and prosperous region,” the Treasury Department stated during President Obama’s last year in office, adding the bank’s “environmental infrastructure projects help promote greater regional stability and diminish migration flows.”

Providing the bank with the ability to make more loans would also increase investment opportunities for U.S. companies to build wastewater treatment plants and other environmental infrastructure.

But under the Trump administration, the Treasury Department recommended no increase in the bank’s capitalization for fiscal 2018. “Treasury is not requesting funding for the North American Development Bank due to budget constraints,” the department stated in its 2018 budget request to Congress.” The Trump administration’s proposed 2019 budget, was released this month, however, calls for a $10 million contribution to the bank’s capital, matching what Mexico had already put in.

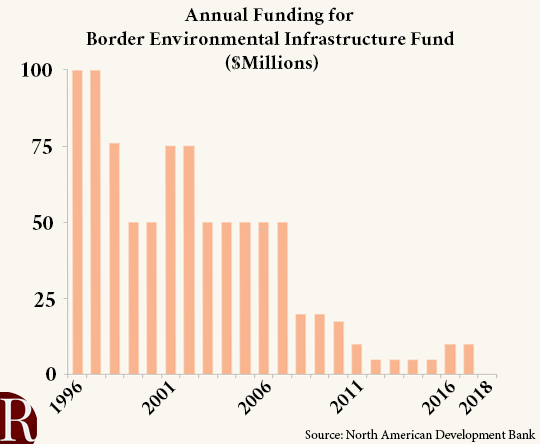

Other sources of funding are also at risk. The EPA’s Border Environment Infrastructure Fund plays a key role in supporting the North American Development Bank’s operations. The grant fund was created in 1996 and was allocated $170 million in the first two years. Funding remained at $50 million a year or more through 2007 before beginning a steady decrease to below $10 million in fiscal year 2017. Trump and House Republicans now want to eliminate funding for the program.

The fund’s grants have played a crucial role in financing development projects by helping make it affordable for financially strapped communities to pay for construction projects. The North American Development Bank, meanwhile, provides construction loans, grants for technical assistance and helps attract money from other public and private sources.

The development bank has awarded $650 million in Border Environment Infrastructure Fund grants since 1996. For every dollar spent, the grants attract $3 in additional funds from other public and private sources, including North American Development Bank loans. Mexico has matched $2 for every $1 in grant funds for environmental infrastructure projects south of the border.

In the past 22 years, the EPA grants have helped finance construction of 59 wastewater treatment plants that are now treating sewage generated by 8.5 million people a day. Thirty-three of the plants were built in Mexico, eliminating 353 million gallons of raw sewage a day that was directly impacting 1.7 million U.S. residents and another 2.3 million indirectly.

“We certainly could use a lot more grant funds,” says North American Development Bank managing director Alex Hinojosa. “There is a huge need.”

Not only is there demand for new projects, many of those initial projects are now coming to the end of their lifespans, spurring a need for a second wave of construction at a time when financing options are evaporating and population increasing.

Old Infrastructure is Collapsing

An as-yet undetermined amount of money is needed to replace collapsing sewer lines, worn out sewage pump stations, antiquated sewer treatment plants and safe drinking water systems on both sides of the border, border financing experts say.

“So, once again we have an infrastructure crisis for basic sewer, water and so on,” says Paul Ganster, the Good Neighbor Environmental Board chairman. “And that’s beginning to have negative effects such as in the Tijuana area. We are a seeing a number of failures in the sewage treatment infrastructure which results in contaminated water flowing downhill and affecting the U.S. side.”

Last November the North American Development Bank approved $1.2 million in EPA grant funds for the rehabilitation of 2.8 miles of a major sewer line in Tijuana. Frequent collapses of the sewer trunk line have contributed to sewage spills into the Tijuana River. Mexico has committed another $1.8 million for the project.

Construction will take two years to complete. The project is just one step in the massive overhaul of Tijuana’s sewer system. There are more than 40 major sewer collectors in Tijuana with failing pipes that contribute to pollution flows into the U.S., bank officials say. Mexico, so far, has only requested funding assistance to repair five sewer lines.

Tijuana is just one of a long list of critical infrastructure projects that need to be built or repaired. The North American Development Bank has 61 projects currently requesting $295 million in funds on both sides of the border.

“We know this is just a drop in the bucket in comparison to the needs that exist,” says Jesse Hereford, a bank spokesman. At the same time as infrastructure needs continue, the EPA grant fund has declined to only $15 million, Hereford says.

There is strong support from border state members of Congress to provide funds for the Border Environment Infrastructure Fund and to increase the development bank’s capitalization. Legislation pending in the Senate includes $10 million for the grant fund for 2018 and doubling the bank’s capitalization. In late January, Sen. Diane Feinstein, D-CA, requested the grant fund receive $20 million. But there is no similar legislation in the House.

A bipartisan group of border state House members has requested House leaders to restore funding for the grant program that was eliminated from a spending bill in committee last year.

“These funds play a crucial role in protecting public health, including those tasked with protecting our borders by reducing sewage runoff and human exposure to bacterial and viral pathogens,” states a Dec. 8 letter signed by 13 House members requesting the House Appropriations Committee include $10 million for the grant program.

Rep. Scott Peters, D-CA, has requested the administration to include much stronger environmental provisions during the ongoing NAFTA negotiations between the US, Mexico and Canada.

“The continued lack of enforceable environmental standards in our trade agreements is no longer tenable,” Peters stated in Dec. 8 letter sent to Robert Lighthizer, the U.S. Trade Representative leading the U.S. negotiations on NAFTA.

“Recognizing that environmental hazards do not stop at transnational borders, it is of the utmost importance that any renegotiated or future trade agreements with Mexico include high-standard, enforceable environmental provisions that empower the United States to stand up for communities through meaningful dispute resolution,” stated Peters, whose district includes San Diego.

But ultimately it comes down to money invested in environmental infrastructure and whether the Mexican and the U.S. governments are willing to spend billions of dollars to protect the health of citizens on both sides of the border.

For communities along the border, the help can’t come fast enough.

Next up:

Our “Border Betrayed” series continues with a look at two small Arizona border communities, each struggling with dangerous environmental health issues.

1 thought on “A Border Betrayed: Communities in U.S. and Mexico at Risk From Sewage, Pollution and Disease”

Comments are closed.