History books tell us that the last wild Barbary lion was probably killed in 1922 by a French colonial hunter in Morocco. But in repeating the story of this well-documented death, the history books may have left a chapter or two out of the story.

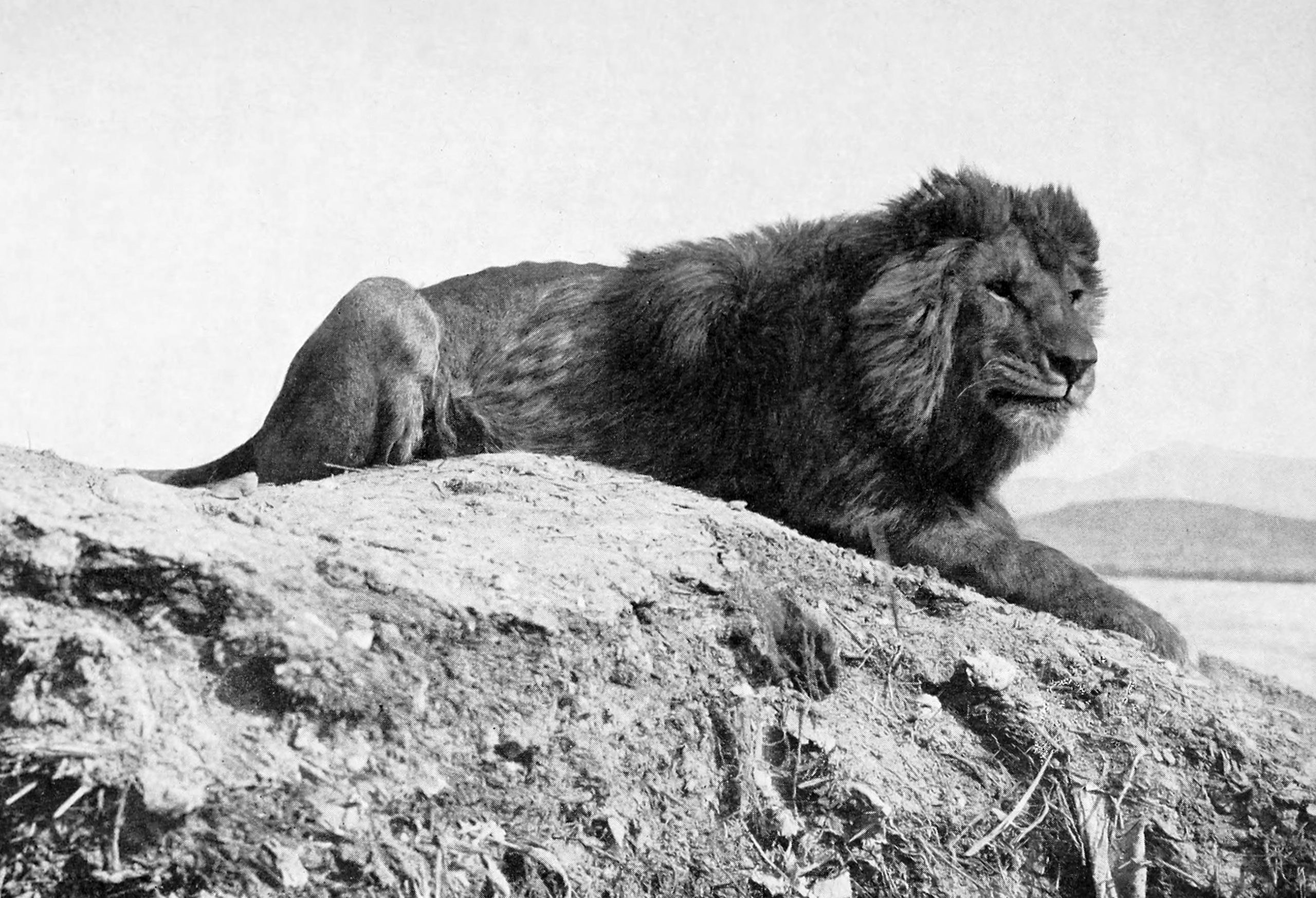

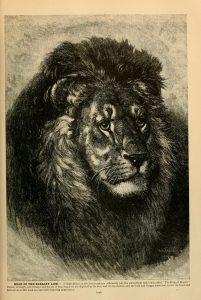

Barbary, or Atlas, lions once roamed throughout the deserts and mountains of northern Africa, ranging from Morocco to Egypt, far to the north of their sub-Saharan relatives. Previously thought to be the largest lion subspecies, they’re now considered a unique population of North African lions. Regardless of their species status, Barbary lions were once upon a time admired for their size and dark manes, although those two qualities have become more mythical over time. Many of these big cats were even kept by the royal families of Morocco and other North African nations.

It wasn’t just Africans who admired them. In Europe the lions famously battled gladiators in the Roman Colosseum, were displayed in zoos and parks, and even lived briefly at the Tower of London.

But that exploitation took a terrible toll. The Romans killed thousands of lions in their games, the Arab empire that followed squeezed the remaining animals into smaller territories, and the influx of European colonialists in the 19th century polished them off. Europeans hunted and killed so many of these animals that they quickly vanished from most of their remaining historic range. None were seen between 1901 and 1910. By the 1920s Western scientists assumed that they were gone.

Or were they? According to research published in 2013 in PLoS ONE, Barbary lions may have remained alive in the wilds of Algeria and Morocco — hidden and safe from most human eyes — for several decades, possibly as late as 1965.

The authors — including Simon Black and David Roberts of the Durrell Institute for Conservation and Ecology in England and Amina Fellous of the National Agency for Nature Conservation in Algiers — combed through published and firsthand accounts of lion sightings in the years after their supposed extinction. They also spoke to dozens of people who said they’d seen or heard stories about living lions well after 1922.

“Our interview work was with old people from remote Algerian communities,” Black told me when the paper came out. “We are fortunate in developing a rich data set since several colleagues have been collecting this information over 10 to 20 years, so our sources are first- or secondhand accounts.” Some of the witnesses they interviewed recalled childhood sightings of the lions. Others recounted tales told by their parents or other family members.

With those sightings in hand, the scientists set out to infer when the lions really went extinct in the wild. That was tough, because the moment of extinction for any species is rarely, if ever, witnessed by human eyes. To develop their dates researchers turned to a 2005 paper published in Mathematical Biosciences that reviewed statistical models using a species’ last sighting to pinpoint when it had most likely gone extinct in the years after the final observation. Black and his co-authors calculated that the Barbary lion probably died out in Morocco in 1948 and mostly likely went extinct in Algeria in 1958. Because we’re talking about statistical probabilities, there’s a confidence interval on that number, suggesting that the extinction date could have been slightly earlier or as late as 1965.

Of course, statistics don’t always account for human behavior. The last sighting the team was able to uncover occurred in 1956 in a forested area in Algeria, when several people on a bus saw a lion just north of the town of Sétif. Black reported that the forest “was destroyed in 1958 during the French-Algerian War, so it is possible the last lions disappeared at that time.”

If ever confirmed, that would make the Barbary lion one of the few proven extinctions caused by the ravages of war.

Why does it matter exactly when Barbary lions went extinct in the wild? Black and his co-authors said this research has relevance for the conservation of the rest of Africa’s lions. Small, fragmented populations in certain regions — typical of lions in areas throughout their range — could require additional attention to ensure their survival. “The diminishing micro-populations of lions in West Africa today mimics the decline of the Barbary lion in North Africa,” Black wrote last year.

They also advocated against declaring any species extinct too quickly. Doing so, they say, could remove any incentive to keep looking for and conserving that species.

But the fate of Barbary lions, as it turns out, is not entirely decided. They may have gone extinct in the wild decades ago, but its genes persist within around 100 captive lions scattered across more than a dozen zoos. These animals, probably none of whom are pure Barbary lions, include descendants of the big cats once owned by Morocco’s sultans and kings. That makes them historically, culturally and genetically important, and they may yet have a role in the conservation of the North African lion, especially the animals in captivity. The lions in Morocco, Black wrote, “may represent nearly half of the captive collection of all northern lions. If we ignore these animals, it will be to our peril.”

(Adapted from an article previously published by Scientific American.)

![]()