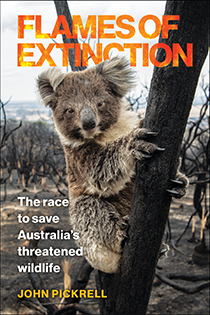

The following is excerpted from Flames of Extinction by John Pickrell. Copyright © 2021 by the author. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington, D.C.

As Christmas approached in 2019, David Crust, a director of park operations with the National Parks and Wildlife Service, watched with trepidation as multiple fires crept their way across the vastness of Wollemi National Park, northwest of Sydney, Australia.

In fact, fires were then ablaze right across the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area, which Crust is responsible for. His entire team of 160 people battled to contain them and protect the townships they threatened.

As the disaster intensified, the fire closed in on the secret location of a tiny population of critically endangered trees; prehistoric plants so precious that just a handful of people are privy to their exact whereabouts.

The Wollemi pine, a conifer that grows to 40 meters [131 feet] and has unusually arranged, dark green foliage and bubbly bark, once flourished across the ancient supercontinent of Gondwana, providing shade and sustenance for the dinosaurs.

But over the eons, the range of this “living fossil” has contracted until just 100 or so mature trees remain, spread over four small groves in Wollemi National Park. The majority are wedged into one sheltered gully, deep in the wilderness. Here, the oldest and largest of the pines, dubbed King Billy, is thought to be around 1,000 years old.

***

Prior to September 1994, this kind of araucaria pine (related to Norfolk pines, hoop pines and monkey puzzle trees) was only known from fossils. That was until NPWS field officer David Noble was on a canyoning trip exploring parts of the wilderness perhaps never infiltrated by humans. After abseiling into one uncharted canyon he stumbled across something puzzling.

“At the time, it was just another weekend canyon trip into the Wollemi wilderness. We were looking for new canyons, abseiling down waterfalls to places where no one had been,” Noble recounted in 2017. “We had completed the descent and sat down for lunch when I noticed a tree that I hadn’t seen before. Without thinking too much, I collected a small leaf sample and put it in my backpack.”

He couldn’t match the leaves to anything he knew, so later that week took the sample to Wyn Jones, a NPWS naturalist. Jones returned to the site with Noble, and quickly realized its significance. It was one of the greatest botanical discoveries of the century.

When Jones and Jan Allen, a botanist at the Blue Mountains Botanic Garden, were involved in describing the species in 1995, they named it Wollemia nobilis in honor of Noble.

The discovery of the Wollemi pine as a living plant “was an incredibly significant botanical find,” says Crust. With a heritage spanning 200 million years, some said it was akin to having found a family of dinosaurs still surviving in one of the dark crevices of our planet.

***

This is why Crust was so concerned as fires engulfed much of Wollemi National Park in December. While fire has threatened the pines before, the lack of moisture here at the peak of the drought was like nothing on record.

“Right at the start of the season, we were concerned … there was the significant potential for large and intense fires,” he says. “We were watching the fires across the park very, very closely … and their behavior was erratic because of the incredibly dry conditions.”

Having had the “privilege” of helping manage the species since 1996, soon after its discovery, Crust wasn’t going to allow it to be lost without a fight.

In early to mid-December, about two weeks out from when the fire finally roared up to the lip of the canyon, it became clear Crust and his team needed to throw into action a previously-thought-out-but- never-implemented plan to save the trees, should the worst ever occur.

This extraordinary operation involved dropping fire retardant from air tankers and helicoptering in specialist firefighters each day, who were winched down into the canyon. From there, they pumped water into an irrigation system to increase the level of moisture in the environment. This daring plan was like nothing ever attempted before in the name of conservation.

But would it be enough to save trees? The Wollemi pine had survived the demise of the dinosaurs, the break-up of the supercontinents and a constantly shifting climate, but now its fate was in the hands of one small crew of dedicated NPWS remote area firefighters.

***

On the night the blaze finally swept the grove, the atmosphere was tense in the fire operation control room, where Crust and his team watched its progress on the remote cameras. But so much smoke engulfed the grove that it was impossible to see if they had succeeded in saving the trees.

As dawn broke the next day, NPWS team member Steve Cathcart headed to the site in a helicopter. He was meant to remain in the air, directing the bombardment of water, but Cathcart could see fires burning below. A gum tree had fallen from the cliff above and was ablaze in the center of the grove.

Breaking the rules, he winched down solo into the grove, where he kicked burning coals away from the base of the Wollemi pines and jerry-rigged melted irrigation pipes so he could pump water up to douse the blaze.

“Given the importance of each and every one of those trees, I knew what I had to do,” Cathcart recounted to The Australian newspaper. “I just happened to be there at that time … I knew that we probably wouldn’t get another opportunity to organize a team [to go down] and that the smoke would probably close in. It had to be me.”

As he was flying out, another helicopter flew in to water-bucket the blaze. The trees had been saved.

Fire had scorched trunks and killed many smaller, juvenile trees, but the canopy of the mature pines escaped unscathed. If it had burnt, the results would have been catastrophic, Crust tells me.

Seen from above, the gorge containing the Wollemi pines was a welcome streak of green amid endless ridges of charred sclerophyll forest. When news of the pines’ survival and the effort to save them hit the press a few weeks later, jubilation broke out at another rare good news story amid all the horror of the past few months.

“We were relieved,” says Crust. “But, we’re still not sure exactly what the impacts will be. The trees have never been impacted by fire in this way since their discovery.”

Most of the mature trees already had some evidence of fire scarring on their bark when they were discovered, suggesting they have some tolerance to bushfires, but it may be many years before the longer-term effects of the 2019 fires on mortality can be determined.

For now, the pines are safe — the entire landscape around them has burned, so there won’t be any significant threat from fires for four or five years. But the challenge will come after that and Crust and his team must plan for managing the threat of fire here into the future.

Copyright © 2021 by John Pickrell. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington, D.C.