Geopolitics in the Arctic are quickly becoming incompatible with the physical and social realities of the region.

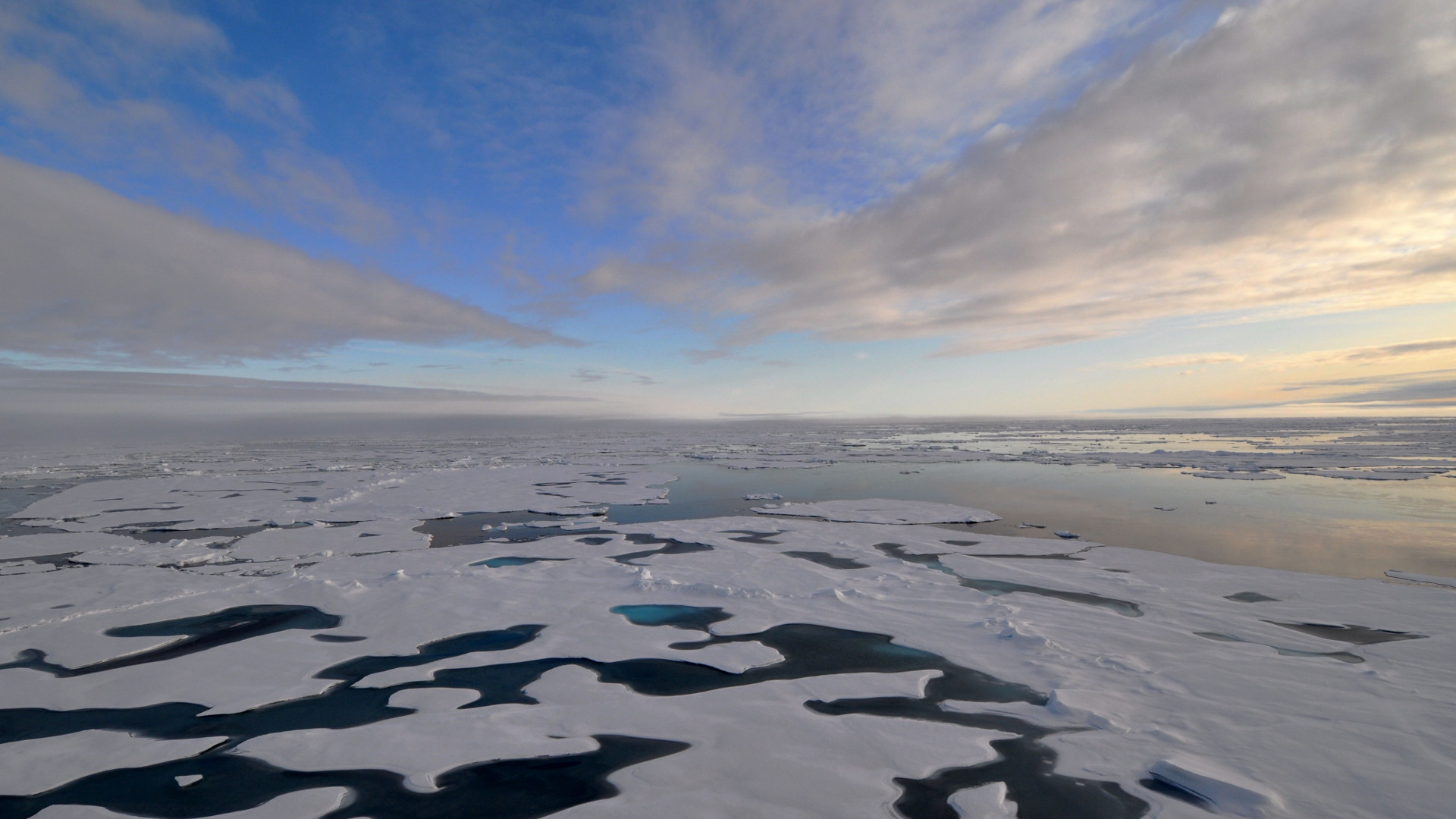

According to NASA, the average amount of Arctic sea ice present after the summer melting season has shrunk by 40 percent since 1980. Winter sea ice has also been at record lows.

As melting ice frees up once-inaccessible sections of the frozen Arctic Ocean, the seven nations around it will have to negotiate new borders — a series of decisions that has the potential to alter the Arctic landscape and make life harder for its people and wildlife.

In 2018 these nations will attempt to answer a question with massive implications: Who owns the Arctic Ocean?

For the nations in the Arctic Council — Canada, Russia, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Iceland and the United States — climate change presents an opportunity for access to brand new waters, previously cloaked in ice, that are chock full of valuable resources.

Russia and Denmark have submitted new territorial claims in 2017, with Canada expected to follow, and it’s up to the United Nations to determine which country gets what in 2018.

How these competing interests are negotiated will affect the whole world, says Andrey Petrov, a Russian scientist, professor and member of the International Arctic Science Committee.

“This should get settled because it applies to both short-term change and long-term impact,” says Petrov. “It’s important to consider how the Arctic is connected to the world, and how climate change and economic interests are changing life for the people living there.”

Differing Claims

The problem is there’s a lot of overlap between each of the three claims. Denmark claims sovereignty over the 347,500 square miles north of Greenland, which includes the North Pole and the contentious Lomonosov Ridge, but so do Russia and Canada. In 2007 the Russian government even went so far as to dive 2 miles below the surface near the North Pole to plant its flag on the seabed.

A potential trove of resources hide in these contested waters, ranging from untapped fishing stocks of cod and snow crabs (in which even non-Arctic nations like China and South Korea have expressed interest), to rare minerals like manganese, uranium, copper and iron below the seafloor.

Nations are also interested in drilling for energy resources in the Arctic, which the U.S. Geological Survey estimate contains 30 percent of the world’s undiscovered natural gas and 13 percent of the world’s oil.

New Arctic oil-development projects and the emissions they create would also exacerbate climate change, the very force that’s providing access to these new resources in the first place. Each year the Environmental Protection Agency publishes a report detailing which U.S. industries contribute the most to carbon emissions — from 2011 to today, oil and gas production is the second biggest polluter of greenhouse gases, behind power plants. Currently at 282.9 million metric tons of CO2 emitted in 2016, this number could be expected to rise with new developments.

But the troubling relationship among carbon emissions, climate change and development in the Arctic isn’t enough to quench a country’s thirst for oil.

The Russian minister for the environment and natural resources told The Daily Telegraph last year that the country was looking for “recognition of exclusive economic rights to about 460,000 square miles, estimated to hold 5 billion tons of hitherto unexploited oil and gas.”

In addition to its impact on global carbon emissions, oil development in the Arctic can damage the environment around drilling sites beyond repair.

This past December the U.S. Senate approved of the Republican tax overhaul, which has hidden in it a provision to approve of drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska, an area that although uncontested internationally, is of huge importance to the native Gwich’in’ people, who fear that oil development will affect caribou, their main source of food.

The fear of a major disaster in the refuge is real, too. According to a 2014 report from the National Research Council, Alaska is ill prepared to respond to a spill or other event, with the nearest Coast Guard station more than 1,000 miles away from the proposed drilling site (which would be capable of releasing 21 million gallons of oil).

The scramble to stake claims in the Arctic also has implications for trade and diplomacy. The United States has challenged Canada’s sovereignty in the Northwest Passage, for instance, arguing that the strait is international, while Canada wants its own maritime laws to apply there.

And national-security interests depend on Arctic territorial claims that will largely dictate which country has military dominance in the area. Over the years Russia has beefed up its military might in the Arctic. According to a report released in September by the Henry Jackson Society, a UK think tank, Russia currently has 45,000 troops, 3,400 military vehicles, 41 ships, 15 submarines and 110 aircraft in the Arctic region — a display of power that makes neighboring countries uneasy.

“We can no longer ignore Russia’s growing military footprint in the Arctic,” noted James Gray, a UK MP and member of the House of Commons Defense Select Committee, in the report. “As the ice melts and new commercial opportunities emerge in the region, Britain and her allies must do more to ensure that the Arctic remains stable and peaceful.”

The Arctic People

Andrei Petrov, as chairman of the International Congress of Arctic Social Sciences — a triennial conference that brings scientists from around the world together to share research on the Arctic — is interested in improving life for the 4 million people in the region’s communities who stand to lose the most from climate change and geopolitical interest.

Petrov says environmental changes in the Arctic, such as flooding, coastal erosion, permafrost thawing, altered migration patterns of both land and sea animals, and a shifting in vegetation zones, have already had drastic impacts on indigenous communities that rely on subsistence hunting and fishing.

According to him, communities in the Arctic are grappling with diet changes, high suicide rates and a degradation of local culture from the tides of globalization that bring big industries to their once isolated and sustainable communities.

“Unfortunately, with most of the development happening today, the local communities receive very little in return,” says Petrov. “Right now we’re at the point where we need social responsibility and a general understanding of human rights in the Arctic. The hope is that development will pay attention to that. It’s important that locals will have the chance to say no to oil development.”

Tricky Negotiations

These high stakes are why clearly defined borders in the Arctic matter, but how are the border claims going to get negotiated?

Currently, under Article 76 of the U.N. Convention of the Law of the Seas, nations have territorial rights to the waters that extend 200 nautical miles beyond their shores. In 2009 Norway was the first country to submit territorial claims to a special U.N. committee, successfully extending its border by 235,000 square kilometers. The United States has not ratified the convention but recognizes it as international law.

If they want to gain access and rights to the new sections of Arctic ocean, Russia, Denmark and Canada need to prove to the United Nations how far their respective continental shelf — the shallow extension of the continent’s landmass under the ocean — actually reaches.

These countries have spent the past couple of years collecting geological data from their submarines and radar in order to prove that the land extending past their established border — 200 nautical miles off the coast of each — is indeed part of their continental shelf.

And if U.N.-appointed geologists can verify the data submitted by each country, then officials there can legally draw new borders and gain new territory, with clear strategic benefits.

“The main thing is that there are a lot of resources there and big interest at play to access them,” says Petrov. “It’s important that eventually we reach some solution about who’s there and what’s the agreement.”

Otherwise competing interests could lead to unregulated construction, overfishing, oil spills and military clashes, which will have consequences not just for life in the Arctic, but for life on the planet.

“These are trans-border issues,” says Petrov. “It’s very important that countries work together.”

In other words, this is a problem the world needs to own.

© 2018 Francis Flisiuk. All rights reserved.