Flames burn throughout the powerful new environmental documentary, Anthropocene: The Human Epoch.

You may burn, too, while watching it — sometimes with rage, other times as though you’re in the midst of a fever dream.

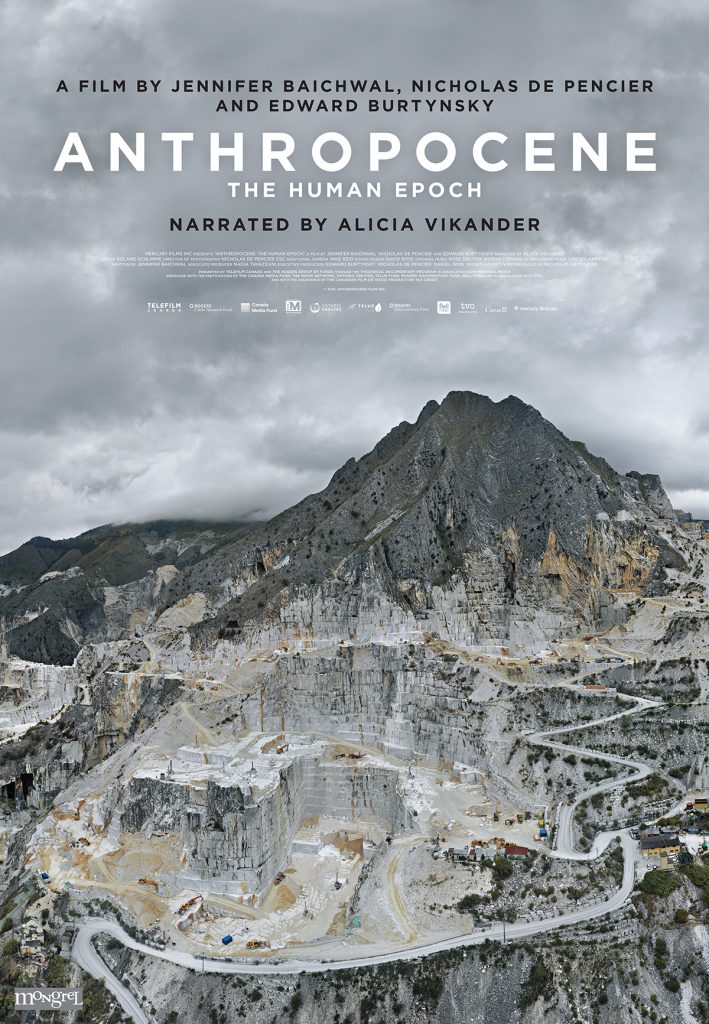

Directed and photographed by the award-winning team of Jennifer Baichwal, Nicholas de Pencier and Edward Burtynsky, Anthropocene takes viewers on a slow-moving journey around the world, to some of its most compromised habitats and landscapes.

We see hundreds of ivory elephant tusks stacked, clattering like dried wood before they’re lit on fire, a conflagration that ultimately roars with burning oxygen and the ghosts of the dead.

We see hundreds of ivory elephant tusks stacked, clattering like dried wood before they’re lit on fire, a conflagration that ultimately roars with burning oxygen and the ghosts of the dead.

We visit a marble mine in Italy, where massive excavation trucks rattle and clank, beep and roar as they drive around miles and miles of nothing but carved-up mountain.

In Nairobi we find other mountains — but no, they’re piles of trash extending as far as the eye can see. Images of the people who live and work there, six million souls, provide context for the sprawling, miles-wide garbage dump. You wouldn’t understand its size and scope without the counterpoint of something as small and fragile as a human life helping to illustrate the nightmare on the screen.

And that’s a common theme throughout Anthropocene. Throughout dozens of similar scenes, the camera moves slowly, often capturing seemingly surreal images from a great distance. These images sometimes take minutes and several transitions to resolve into something we recognize — and then the truth only becomes crystal clear due to the juxtaposition of, say, a person or piece of machinery against the impenetrable background.

The pattern repeats throughout the film, allowing the camera and the soundtrack to tell the story, rarely interrupted by narration or the voices of people on the ground. It’s reminiscent of the leisurely horror of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, or the hallucinatory audio of Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil — but it’s all too real.

Along the way the filmmakers — who put more than four years of travel into the documentary — take us to several places everyday people simply aren’t meant to see. One of the most notable: the Shengli oilfield in China, where workers have spent the past 20 years building a wall to protect the wells from sea-level rise — a project one man says could keep them busy for another 50 to 100 years.

It’s an eye-opening film, and you can’t look away. The horror is hypnotic.

Yet Anthropocene is also a film of great beauty and majesty. Amidst the destruction the shapes and colors of the natural and unnatural world reveal the magic of the planet and the dark spell we’ve cast upon it. The camera lingers over every detail. The microphones catch every rumble, whisper and rain drop. The sound and vision layer over each other, combining to create an immersive pictorial and auditory experience.

This unusual movie is an 87-minute guided tour, and each chapter progresses and moves forward through a series of trick-of-the-eye revelations, but the film rarely imparts direct information. The narration (by Swedish actress Alicia Vikander, who played Lara Croft in the most recent Tomb Raider movie) is emotionless, stark, and designed to do little more than introduce each of the film’s chapters, covering themes such as extinction, climate change and “technofossils” (the garbage that becomes part of the geologic record).

And while some of the people we observe in the chaos are heard on-screen, they’re never identified by name or role, only by the context of their environment. As ivory tusks are stacked like hollow cordwood, for instance, we hear someone say, “This tusk probably came from an elephant I knew. I wasn’t able to stop this elephant from dying. But I can certainly stop it from being desecrated further.” But we never learn the speaker’s identity or role in the story.

While that creates a layer of separation from the speaker, it also works. The lack of a strong human character in the film — combined with the slow barrage of weighty images and crushing sounds — makes you, the viewer, the human in the scene. It’s your eyes seeing it all for the first time, and in some ways your responsibility.

And for me that was the film’s central message, as stated in its final moments: The human tenacity through which we created this mess will also provide the solution and the hope for change.

Anthropocene doesn’t claim a specific solution is forthcoming, but it does present us with enough examples of how people have changed the world to make the strongest possible case for change — while there’s still something left to save.

For more: Anthropocene: The Human Epoch is the latest effort from The Anthropocene Project, an ongoing multipart film/book/museum project examining human influence on the Earth. The film is currently available on several video-on-demand platforms.

![]()