A herd of emaciated cows crowd for water at a small dam in the Zimunya area about 50 kilometres (31 miles) south of Zimbabwe’s eastern border city of Mutare.

On the other side of the small dam, a group of children excitedly fetch water, mostly for nondrinking or cooking uses. In this part of the country, water became scarce this year as an El Niño-induced drought — the worst in more than 40 years — ravaged the region. The drought has left nearly 10 million people food insecure. Livestock and people now compete for limited water in many rural areas of Zimbabwe.

At the same time, livestock diseases are killing the few cattle that have survived the current and previous droughts. The mix of severe droughts and devastating diseases are making both livestock and rain-fed crop farming in Zimbabwe increasingly untenable. And farmers are worried; summer seasons are becoming shorter — in some cases accompanied by violent storms and heavy flooding.

“We don’t even know how to save our cattle,” says Leonard Madanhire, a small-scale livestock and crop farmer in Zimunya. “The cattle might survive the drought, but we are not sure whether they will survive the diseases like anthrax and theileriosis. Most of our livestock are now too frail to fight diseases.”

Anthrax, a disease that affects wild animals, livestock, and humans, is caused by spore-forming bacteria called Bacillus anthracis. Theileriosis, also known as January disease, is a cattle disease transmitted by ticks.

Anthrax is of particular worry. Early this year several districts in Zimbabwe were hit by an anthrax outbreak that caused a documented 513 human infections, countless livestock infections, and 36 livestock deaths.

To contain this year’s outbreak, the Zimbabwe government imported 426,000 anthrax vaccine doses — 25% of what it initially said it needed — from Botswana. The medicines were deployed in hotspots like Chipinge, Gokwe North and South, Mazowe, Makonde, and Hurungwe.

The government also said it carried out public-awareness campaigns about anthrax risks “to ensure that people are well-protected,” according to statements in The Herald, a state-owned newspaper.

Education on the risks is important: People can be infected by anthrax through breathing in spores, eating food and drinking water contaminated with spores, or getting spores in a cut in the skin. Flu-like symptoms such as sore throat, mild fever, fatigue, and muscle aches are common. Other symptoms include mild chest discomfort, shortness of breath, nausea, coughing up blood, painful swallowing, high fever, and trouble breathing. Animals infected by anthrax may stagger, have difficulty breathing, tremble, and finally collapse and die within a few hours, according to experts.

Eddie Cross, a livestock expert in Zimbabwe, says anthrax poses a serious threat to humans and livestock in Africa.

Anthrax “can survive in the ground for many years and then be activated by appropriate conditions,” says Cross, who is also a former legislator and advisor to the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe. “People eating meat from an infected animal run a risk of catching the infection themselves.”

Modern Problems, Historic Cause

Though some experts say the current anthrax outbreaks in Zimbabwe have been exacerbated by climate change, outbreaks can be traced back to the time of Zimbabwe’s protracted war of liberation that ended in 1979. At the height of the war, when the country was still known as Rhodesia, the brutal colonial regime of the late Prime Minister Ian Smith reportedly used anthrax as a biological weapon.

Experts say this resulted in the largest global human anthrax outbreak, which occurred in Zimbabwe between 1978 and 1980. More than 10,700 cases of human anthrax and 200 deaths were recorded during that time.

Since the late 1970s and early 1980s, the disease has become endemic in Zimbabwe.

Victor Matemadanda — a veteran of the 1970s liberation war and secretary general of the Zimbabwe National Liberation War Association — confirmed to me that many of his colleagues died from suspected anthrax infections. The association is a grouping of former freedom fighters, also known as guerrillas or comrades, who served during the country’s war of liberation (also known as the Rhodesian Bush War). The war culminated in the end of minority white rule and Zimbabwe attaining independence in 1980.

“Many freedom fighters died, I can confirm that,” says Matemadanda, who is also Zimbabwe’s ambassador to Mozambique. “But back then we were not sure whether it was anthrax or not because there was no scientific research to confirm that. But the signs and symptoms showed it was anthrax.”

Unfortunately, due to a lack of knowledge back then, many cases could not be confirmed as anthrax infections. Even some medical doctors were not familiar with anthrax symptoms in humans during that time.

Little has changed. One 2016 study revealed that grossly unusual epidemiological features of the anthrax outbreaks in the late 1970s and early 1980s still have not been definitively explained. However, the authors, from the University of Nevada–Reno, widely agree with a hypothesis proposed by Meryl Nass, an American physician living in Zimbabwe at the time of the outbreaks who suggested that the anthrax epidemic was propagated intentionally.

“Nass emphasized the unusual features of the epidemic: large numbers of cases, geographic extent and involvement of areas that had never reported anthrax before, lack of involvement of neighbouring countries, specific involvement of the Tribal Trust Lands versus European-owned agricultural land, and coincidence with an ongoing civil war,” the study notes.

Witness testimony from some people who lived on Tribal Trust Land — areas reserved for Indigenous Black people during the colonial era — revealed a belief that “poisoning” by anthrax occurred during the war, according to the study. The researchers cited other authors who provided testimony of deliberate anthrax releases during the war by Rhodesian soldiers with support from South African forces. And they say that these activities were part of apartheid South Africa’s biological weapons program, code-named Project Coast.

During the war Rhodesia was under United Nations economic sanctions and was isolated from the rest of the world, although it maintained a close relationship with apartheid South Africa. Through South Africa, Rhodesia Prime Minister Smith managed to bust the U.N. sanctions to fund the war, which lasted for more than a decade.

A New Threat Rises

Today experts fear that anthrax outbreaks in Zimbabwe will become worse due to climate change, which is making some parts of the country warmer and wetter.

Les Baillie, a professor of microbiology at Cardiff University’s School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences in the United Kingdom, tells me that outbreaks of anthrax regularly occur in Zimbabwe and that there have been several outbreaks across Africa since last year.

Baillie shared a report on anthrax he recently wrote with Alexandra Cusmano, another expert from the school, which suggests that climate change may have worsened the anthrax problem in Africa.

Oddly enough, the evidence for their hypothesis comes from a 2016 anthrax outbreak in reindeer in northern Russia. There, anthrax killed thousands of animals and affected dozens of humans on the Yamal peninsula, in Northwest Siberia. Experts, the report adds, identified two primary factors as contributing to this outbreak: a summer heat wave that caused the permafrost to melt, releasing “trapped spores,” and the cancellation of the reindeer vaccination program in 2007, which led to an increase in population susceptibility.

Baillie and Cusmano conclude that: “Outbreaks of anthrax in endemic regions of the world are not unusual. We are likely to see more cases due to a combination of climate change and socio-economic factors, such as food poverty and lack of access to effective veterinary services.”

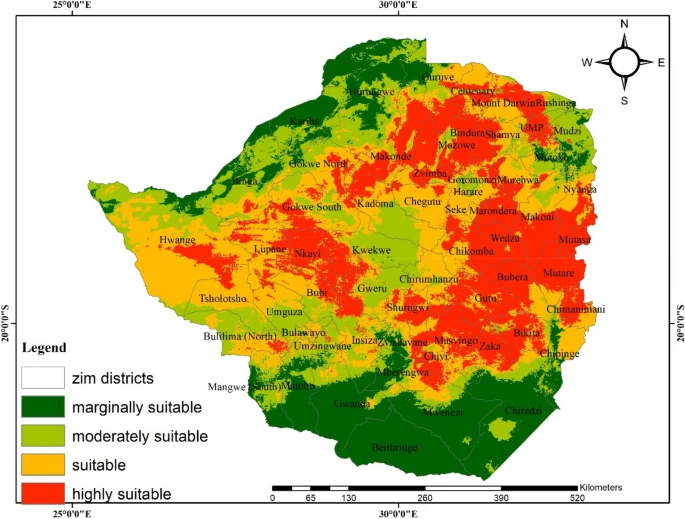

Another study, published in the journal BMC Public Health this year, modeled the future of anthrax outbreaks in Zimbabwe under climate change. The researchers found that the country’s eastern and western districts will face the greatest threats. These districts are home to thousands of small-scale farmers who depend mostly on livestock and crop farming. The study calls for disease surveillance systems, public-awareness campaigns, and targeted vaccinations, among other control measures.

Cross, the Zimbabwe livestock expert, agrees, and says the government should make sure that farmers are aware of the dangers of coming across the carcass of a cow who has died from unrecognized causes. Anthrax infections in humans are mostly by exposure to contaminated animals or their meat.

“[Farmers] should be extremely careful in the way they approach the carcass and, if possible, they should arrange it to be burned, which is the only real way of ending the infections,” Cross says.

Meanwhile, the government says plans are underway to produce enough anthrax vaccines locally starting next year, which could help to eradicate the disease.

But the collapse of Zimbabwe’s economy may complicate the fight against livestock and human diseases. Political and economic crises that unfolded following the country’s controversial land-reform program — which started in 2000 — resulted in negative growth rates, skyrocketing inflation, decline in the rule of law, and a disintegration of markets, according to experts. At the same time, the country has become isolated on the international stage due to its frequent human-rights violations.

Time will tell whether Zimbabwe can succeed in eradicating anthrax. But for now the legacy of this wartime bioweapon continues to haunt the country, more than four decades after it was unleashed.

Previously in The Revelator:

5 Ways Environmental Damage Drives Human Diseases Like COVID-19