When longtime environmental journalist Ben Raines started writing a book about the biodiversity in Alabama, the state had 354 fish species known to science. When he finished writing 10 years later, that number had jumped to 450 thanks to a bounty of new discoveries. Crawfish species leaped from 84 to 97 during the same time.

It’s indicative of a larger trend: Alabama is one of the most biodiverse states in the country, but few people know it. And even scientists are still discovering the rich diversity of life that exists there, particularly in the Mobile River basin.

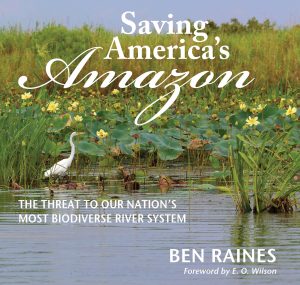

All this newly discovered biodiversity is also gravely at risk from centuries of exploitation, which is what prompted Raines to write his new book, Saving America’s Amazon: The Threat to Our Nation’s Most Biodiverse River System.

The Revelator talked with Raines about why this region is so biodiverse, why it’s been overlooked, and what efforts are being made to protect it.

What makes Alabama, and particularly the Mobile River system, so biodiverse?

The past kind of defines the present in Alabama.

During the ice ages, when much of the nation was frozen under these giant glaciers, Alabama wasn’t. The glaciers petered out by the time they hit Tennessee. It was much colder but things here didn’t die.

Everything that had evolved in Alabama over successive ice ages is still here. We have a salamander, the Red Hills salamander, that branched off from all other salamander trees 50 million years ago. So this is an ancient salamander, but it’s still here because it never died out.

The other thing you have here, in addition to not freezing, is that it’s really warm. Where I am in Mobile, we’re on the same latitude as Cairo. So the same sun that bakes the Sahara Desert is baking here.

But we also have the rainiest climate in the United States along Alabama’s coast. It actually rains about 70 inches a year here. By comparison, Seattle gets about 55 inches. It makes for a sort of greenhouse effect where we have this intense sun and then plenty of water. Alabama has more miles of rivers and streams than any other state.

Things just grow here.

The pitcher plant bogs of Alabama, for example, are literally among the most diverse places on the planet. In the 1960s a scientist went out and counted every species of flowering plant in an Alabama pitcher plant bog. He came up with 63. That was the highest total found on Earth in a square meter for a decade or more.

For a long time the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was thought to be the center of oak tree diversity in the world because they have about 15 species of oaks in the confines of the park. Well, two years ago scientists working in this area called the Red Hills along the Alabama River found 20 species of oak trees on a single hillside. It’s just staggering.

Why is Alabama’s rich biodiversity not well known or studied?

The state was never known for being a biodiverse place until the early 2000s, when NatureServe came out with this big survey of all the states. It surprised everyone because it showed Alabama leading in aquatic diversity in all the categories — more species of fish, turtles, salamanders, mussels, snails.

This blew everybody away because Alabama in everybody’s mind is the civil rights protests of the 1960s, the KKK, steel mills and cotton fields. But that’s not what’s in Alabama, that’s what we’ve done to Alabama since we’ve been here.

I think part of it also has to do with being a long way from Harvard and Yale and Stanford and the great research institutions that were sending biologists all over the world. Alabama just wasn’t really studied or explored.

Again and again, the story in Alabama is that nobody has ever looked.

That’s one of E.O. Wilson’s big messages about Alabama. He is our most famous living scientist, I would say, or certainly biologist. He grew up here, and now in his twilight years his big mission has become trying to save Alabama. And he describes it as less explored than Borneo and says we have no idea what miracle cures and things we may find in the Mobile River system, which is what I call “America’s Amazon.”

As you write about in your book, all this newly discovered biodiversity is at risk. What’s happening?

Alabama is in a very precarious situation. We have the worst environmental laws in the country and the state environmental agency has been the lowest funded of any state going back decades. So there’s very little enforcement. Maybe that’s because nobody realized how rich this place was in terms of diversity, so there was no move to protect it.

But Alabama’s early history, from the discovery of coal, which happened in the 1800s, has been one of exploitation. Massive amounts of forests were taken down in the 1800s for cotton fields. This state produced more cotton than any other back then, and that took a huge natural toll. And typically it’s people from other places, or even other countries, coming here to harvest the natural resources.

When I was born in Alabama in 1970, there were 15 steel mills in Birmingham going full blast. The air and water pollution from the steel mills and the coal mines were on a scale that’s almost unbelievable.

So even when we talk about the biodiversity we have now, we can’t even imagine what we’ve already lost. And this history of exploitation is still going on today. The largest factory built in the United States in the last 25 years was built in Alabama.

Alabama is inviting industry — and industry is coming because you can get a permit here in 30 to 60 days from the state environmental agency. That same permit in California would probably take 10 to 20 years to secure.

One example is the way Alabama does water permits: There’s no limit on how much water industries can take, no matter what environmental havoc may occur.

A couple of years ago we had droughts so bad we actually saw some of the state’s major rivers run dry. The Cahaba River is 150 miles long and it has 120 fish species — more than in the entire state of California.

And during this drought, the industries and golf courses were allowed to suck so much water out of the river it went dry. It only started flowing again downstream from a sewage plant. The entire flow of one of the most diverse rivers in America was the outfall from a sewage plant. It’s the kind of thing you can’t imagine happening in the United States, but it happened here and there were no laws to stop it.

Are there forces pushing back against this, and are people beginning to see the value of Alabama’s biodiversity?

Environmental groups here are having an amazing growth spurt. Twenty years ago our Baykeeper group, which is part of the Riverkeeper alliance, was a one-woman show.

Now it has about a dozen employees and a huge membership. There are many other environmental groups now that have appeared and are doing good work all over the state.

That’s a big change.

As ecotourism is spreading across the country, it’s starting to happen here, too. The state is quickly catching up. There was great outrage among the populace when I wrote a story about the rivers running dry and now there’s an effort at the state level to make a water plan and to actually limit how much water industry can take.

It sounds like there’s still a long way to go for Alabama to catch up with environmental regulations — what else would you like to see happen?

I write a lot in the book about wetlands because so much of our diversity is in these edges where water and land meet. I would like to see the edges protected, but of course the problem is that’s where people want to be. They want to live on the river, on the bay, on the beach. When you couple that with rising sea levels, there’s a collision that’s coming between people and the edges.

We have to protect that intertidal habitat now and then buy the uplands behind it to get ready for sea-level rise because otherwise our coastal habitats will have nowhere to go.

I would also really like to see Alabama adopt the pollution standards that you see in the surrounding states. For reasons that escape me, the levels of PCBs in fish we allow people to consume before we issue a warning is 10 times higher than any other state. There’s no scientific reason why we would be so far out of step with our neighboring states.

And then there’s the extinction issue. The rate of extinctions in Alabama is roughly double that seen anywhere else in the continental United States. It has more extinctions than Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia, Florida and Tennessee put together.

We’re going to go from being the king of diversity to the king of extinctions. And that’ll be a terrible thing not just for Alabama, but for what we know about nature. Alabama has more than twice as many species per square mile as any other state. And if we start losing that diversity, we’re going to have no idea what we’ve lost.

What do you hope people do after reading your book?

I would hope they come to Alabama to see some of these things, because that’s what will make the powers that be care — when ecotourism becomes an industry that can rival industrial manufacturing, then ecotourism will carry as much weight among the lawmakers.

I’ve been here about 20 years, much of that time as the environment reporter for the state’s three biggest newspapers. Those papers were the environment’s best friend. But they’ve been basically destroyed. The papers are just too anemic. In Mobile, we had a newsroom with 90 people in it, and now they have three reporters. The last thing you’re going to see is an in-depth environmental story anymore.

So the book is a love letter and it’s a call to arms, and it’s saying, “love this place, but help.”

I guess at the end of the day, the story in Alabama about the natural world has been a story of taking and never giving back or appreciating what was here in the first place. That’s what has to change. Because if you just keep taking, you know how it will end. There’ll be nothing left.

![]()