Should nature have rights? That question is being put to the test right now in Ecuador.

In 2008 the South American country made history when its new constitution declared that nature had “the right to integral respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its life cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes.” It was an unprecedented commitment, the first of its kind, to preserving biodiversity for future generations of Ecuadorians.

The constitutional change did not automatically protect nature, but it gave citizens what the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature describes as “the legal authority to enforce these rights on behalf of ecosystems. The ecosystem itself can be named as the defendant.”

The country could soon make history again when its Constitutional Court hears a case that seeks to apply these rights of nature to a protected forest, known as Bosque Protector Reserva Los Cedros, against large-scale copper and gold mining.

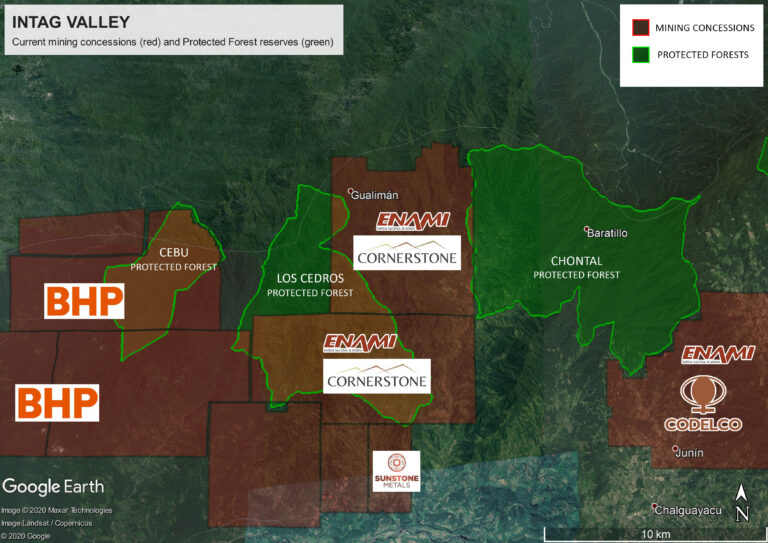

The threat stems from a 2017 change in government policy that allowed mining concessions on 6 million acres of lands, including at least 68% of Los Cedros — part of a hasty attempt to boost the mining sector and compensate for declining oil revenues. Experts say that policy appears to be unconstitutional, which has led to the present showdown.

“Mining in protected forests is a violation of Articles 57, 71 and 398 of the constitution: the collective rights of Indigenous peoples, the Rights of Nature, and the right of communities to prior consultation before environmental changes, respectively,” says ecologist Bitty Roy of the University of Oregon, who has conducted research at Los Cedros since 2008.

A Vital Reserve

Los Cedros is a remote, pristine, 17,000-acre cloud forest in northwest Ecuador and one of the most biodiverse places on the planet.

Conservation biologist Mika Peck, of the University of Sussex, describes Los Cedros as “a biodiversity hotspot within a hotspot — and of global importance in terms of conserving our natural history.”

He adds, “the reserve and all it maintains is priceless.”

The reserve has been protected since 1988 due primarily to the work of manager Josef DeCoux and Australia’s Rainforest Information Center.

DeCoux tells me he was one of the “hippies” who moved from the United States to Ecuador in the 1980s to help “save the rainforest.”

He chose well. Not only does Los Cedros protect at least 250 species from extinction, it safeguards four watersheds. That means the court case is not just about preserving a biodiversity jewel; it’s about guaranteeing a livable environment to local people as well as protecting the forest’s own right to remain undisturbed.

A 2017 letter from 23 international scientists, including Roy and Peck, argued that “the value of this intact watershed is far greater than that of any possible mineral wealth that lies beneath it.” Another letter, released last month, called for the protection of Los Cedros and other protected areas from mining and carried signatures from conservationists Jane Goodall, E.O. Wilson and 1,200 other scientists.

The remoteness of the reserve was one of the things that pulled me to it a few years ago.

Inaccessible by road, the final ascent up to Los Cedros is a nerve-wracking, two-hour mule ride on a muddy track with sheer drop-offs and awe-inspiring views. Once there you’re immersed in a biological paradise. You can walk among the shaggy, epiphyte-laden trees dripping from the frequent rain showers brought by the low-creeping clouds; listen to the cacophony of some of the 358 bird species that greet the dawn; seek out the six species of cats, including pumas and endangered jaguars; get to know some of the 970 species of moths; or look for 186 species of orchids, one-third of which are endangered. They include several species of Dracula orchids, named for their blood-red petals and haunting faces.

Each day I explored the reserve’s trails — kept short to minimize disturbance to the ecosystem — its uniqueness became more evident. Nearly two dozen species of frogs, almost all endangered — including a species of rainfrog able to change its skin texture and a glass frog known for its transparent abdomen — occupy streams so clean you can drink directly from them. During my visit DeCoux told me he was particularly proud of that pristine resource.

The reserve is also home to the endangered spectacled Andean bear and three species of monkeys, also endangered.

On a morning hike with one of the guides employed by the reserve, I saw a troop of one of those species, the critically endangered brown-headed spider monkey, one of the rarest primates in the world, with a population of about 250 individuals. As most of the troop moved on, one monkey hung back to grab and eat some fruit. Although we watched from 30 yards away, it soon started hooting at us and shaking a branch to scare us off.

A clear message that we’d encroached on its personal space.

The Mining Threat Looms

Yet in an encroachment of national and potentially devastating proportions, in 2017 the government put more than two-thirds of Los Cedros under a mining concession to the Canadian mining company Cornerstone Capital Resources, in conjunction with ENAMI, the state’s mining company.

More than seven million acres across Ecuador are now under concessions. Additional concessions cover major portions of Indigenous territory, which threatens not only the people’s livelihoods but their lives. The permits, the majority of which are in the highly biodiverse Andean cloud forests, were issued without consulting the affected communities.

A year ago DeCoux’s legal team succeeded in getting a provincial court to revoke Cornerstone’s mining permit because of the lack of consultation. But that hasn’t stopped the company from continuing to operate, according to Elisa Levy of the mining oversight collective OMASNE (Observatorio Minero, Ambiental y Social del Norte del Ecuador).

“They have built roads to the edge of the reserve,” she says, “and broken new trails in Los Cedros” — actions that compromise the integrity of the presently intact ecosystem.

ENAMI appealed the provincial court’s decision, and in May the Constitutional Court decided to hear the case under rights of nature, probably by the end of the year.

The latest development was “very good news indeed,” DeCoux wrote in a blog post. Without rights people perceive forests, rivers and oceans as objects to be used; but with rights they become subjects to be valued on their own terms.

The case matters not just for Los Cedros — it could set precedent for the entire country.

Two of the Constitutional Court judges, Ramiro Avila and Daniela Salazar Marin, issued a written statement on May 18 that acknowledges the biodiversity of Los Cedros and explicitly mentions that it is the home of the critically endangered brown-headed spider monkey and the endangered spectacled Andean bear. They further argue that the case will allow the court to rule on the “content” of the rights of nature, and to “develop parameters to set the limits of protected forests and the scope of responsibility for the state to monitor and follow up on mining concessions.” (Translated from Spanish.)

The Call to Protect

Habitat loss, now exacerbated by climate change, is the leading cause of extinction around the world. With the high number of endemic species in Los Cedros, and their small range, allowing mining exploration to continue will undoubtedly result in extinctions. In a research paper published in 2018 in the journal Tropical Conservation Science, Roy and others argue that permanently protecting Los Cedros, the last uncut forest in western Ecuador, is necessary to ensure lower-altitude flora and fauna can migrate freely to the higher altitudes found to the north, where Los Cedros borders the enormous 450,000-acre Cotacachi-Cayapas Ecological Reserve.

Peck echoes that conclusion. “The move to rule in favor of Bosques Protectores such as Los Cedros is vital to ensure protection of vital natural habitats, and the species they maintain, in a world that is going to undergo major climatic shifts,” he says. “Natural habitat is key to maintaining ecosystem services that buffer these changes and allow species to migrate and survive.”

Those species remain ever-present in my mind.

The sound I most remember from Los Cedros is the eerie call of the pastures frog: a high, slow electronic bleating that reverberated back and forth over the ridge — as if to warn that all this could be lost. Reserves like Los Cedros make up one-third of the protected lands in Ecuador, so a ruling in favor of rights of nature here would be a bold move that would protect other forests from mining and ultimately allow the establishment of new conservation corridors.

If ever there was a time for bold moves that will surely make history, it is now.

Peck calls a ruling in favor of the Bosques Protectores “the only rational response in the face of climate change and biodiversity loss.”

Levy is encouraged that the case will be heard under rights of nature, but remains cautious. “We don’t want to be too optimistic,” she says. “We know what’s at stake.”

For more on Los Cedros and the threat of mining in Ecuador, watch this video from the Rainforest Action Group:

![]()