Two rifle shots ring out in the forest. It’s the year 1812 in Louisiana, and naturalist John James Audubon has just bagged himself two elusive birds for his collection: a nesting pair of massive, beautiful ivory-billed woodpeckers.

Upon returning home that evening, Audubon holds his prizes up for his wife to see. “They’ve become such a rarity,” he says to her. “I must paint them quickly before their plumage loses its lustre.”

It’s a sad, melancholy moment. The resulting painting of those two dead woodpeckers — plate 66 in Audubon’s fabled Birds of America — depicts a species that has since disappeared into extinction.

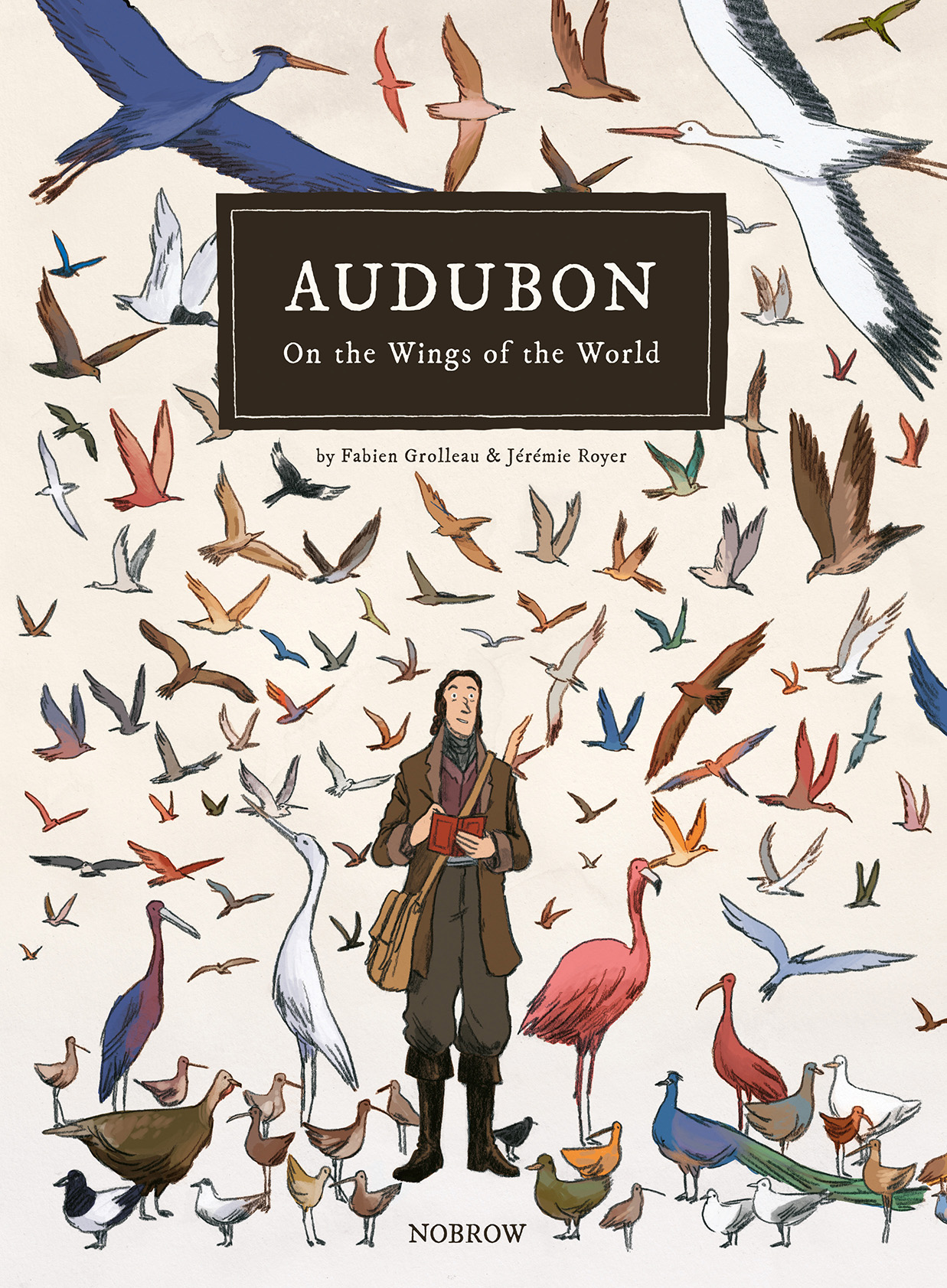

This scene, like many others like it, plays quietly in the new graphic novel, Audubon: On the Wings of the World, by French writer Fabien Grolleau and Belgian artist Jérémie Royer (Nobrow Press, $22.95). The book presents a complex portrait of the iconic 19th century naturalist, showing him as a visionary scientist, a brilliant painter, and a bull-headed eccentric who lived more for his birds than for the people around him.

Audubon, as Grolleau and Royer show us, lived at a time when science had only just started to effectively catalog the world’s species, but also at a time when the wildlife of the world had already begun to disappear, leaving great gaps in their wake. In another scene from the book, the naturalist watches as a flock of a billion passenger pigeons flies overhead, a process that takes three full days before the birds finally stop blotting out the sky. The species went extinct about a century later.

In another resonant scene, Audubon arrives at a Mississippi logging camp. The man in charge tells him over dinner, “If only you’d paid us a visit ten years ago. I would have been able to show you magical, secret areas of the woods. You would’ve discovered bird species that exist only here. If only you know how much I miss these wonders…”

Audubon responds in a curious manner, saying “I believe we’re coming to the end of the age of the great forests, but have we the right to be nostalgic about it? If in their place a great national arises, is the game not worth the candle?”

Still, despite his apparent praise of development and progress, the rapidly disappearing frontier apparently weighed heavily on Audubon. Later in the book Grolleau and Royer depict a moment when the artist — still short of success and his health in ruins — paints frantically, trying to capture the birds of this “Garden of Eden” before the “white man” wiped them all away.

And yet Audubon contributed to some of that himself. He shot the birds that he painted, then posed them to replicate the behavior he witnessed in the wild. “I often say that if I shoot less than 100 birds a day, they must be rare,” he is quoted as saying.

Ultimately, the book celebrates Audubon’s scientific, artistic and (eventually) financial success. His achievement at painting so many North American birds became a sensation and changed the very idea of the way scientific art should display the natural world. Along the way he inspired generations of men and women to follow in his footsteps, to help preserve the natural world that he witnessed starting to disappear more than 200 years ago.

Books such as this can only help to continue that legacy. Grolleau and Royer tell Audubon’s story masterfully. They don’t shy away from his complexities, such as how he abandoned his family for years at a time, or the fact that he killed so many birds to accomplish his research or art, or his less-than-illuminated perceptions of Native Americans and African slaves. But they also bring Audubon’s love of nature to life. Royer’s cartoony art style is significantly simpler than Audubon’s detailed paintings, but the book is filled with delightful and touching details. There’s something quiet and subtle and often magical to enjoy on every page.

The world has changed a lot since Audubon’s day, but the same plight of disappearing habitats and species remains. Maybe we need more obsessed explorers like him. In any case, revisiting his story is a reminder of what we’ve already lost, and what we’re likely to continue to lose without people such as John James Audubon.

Related: