Ticks have been making headlines recently. Whether it’s due to tick-borne disease, range expansion, or the emergence of invasive tick species — as far as most folks are concerned, ticks are bad news. And to an extent this is true, although only a small number of tick species actually threaten the health of people and their pets. The vast majority of tick species leave humans well alone and actually serve important roles in their ecosystems.

Unfortunately a few of these harmless ticks are teetering on the brink of extinction, including one that’s just been discovered.

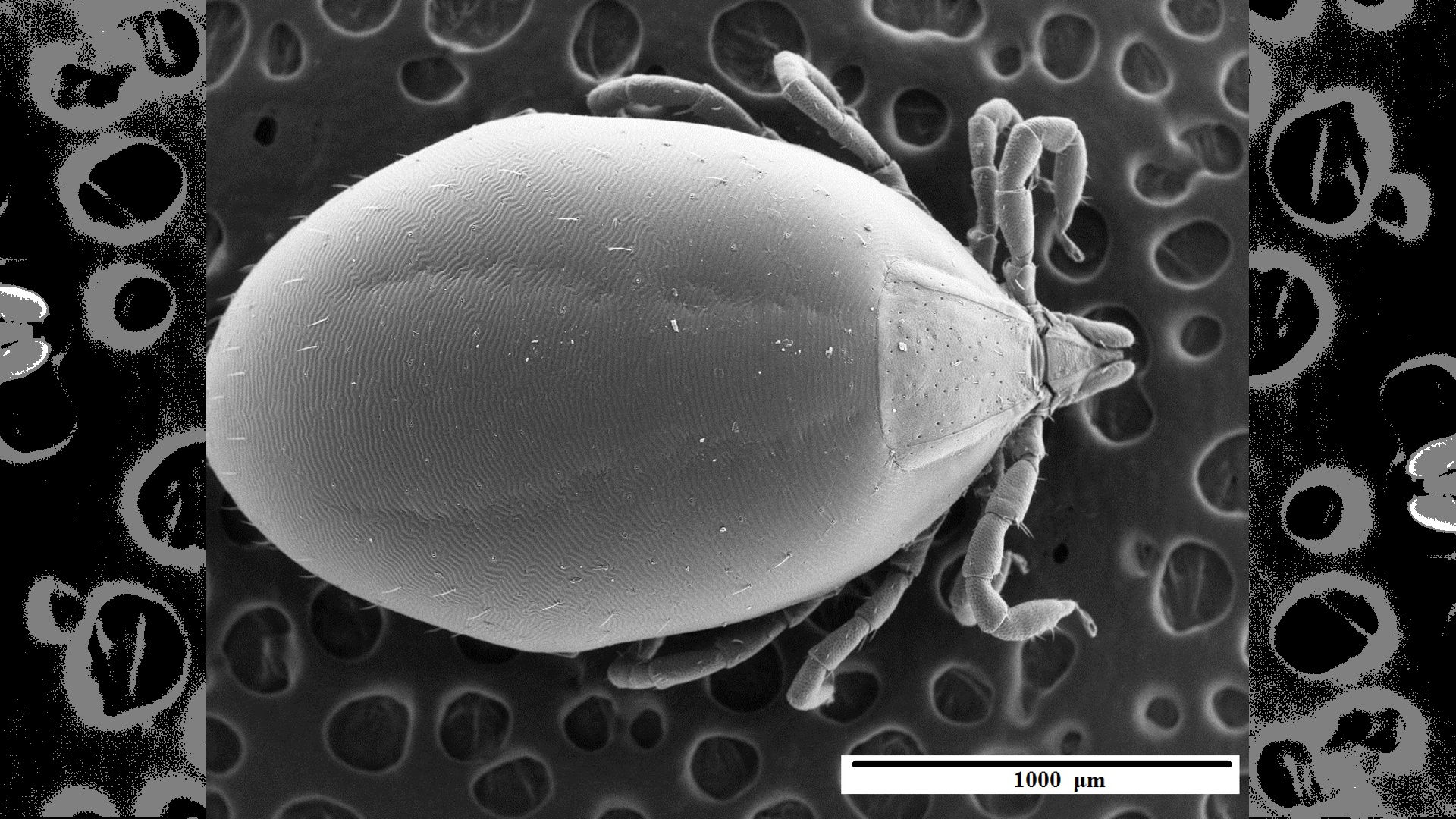

Each year a team of conservationists from Zoos Victoria head out to survey wild populations of the mountain pygmy possum (Burramys parvus). These cute little marsupials live in alpine boulder fields on some of Australia’s highest peaks and are listed as critically endangered by the IUCN. While undertaking health checks last year, the team stumbled upon some small ticks riding along on the possums, and a few samples were taken and forwarded to my lab. I examined them, and their distinctness was immediately obvious. In conjunction with the team at Zoos Victoria, we have described them as a new species: Heath’s ticks (Ixodes heathi), which we named after the eminent tick biologist Allen C.G. Heath.

Apart from the fact that this is only the second endemic tick species to be described from Australia in the past 20 years, what was so surprising was the fact that Heath’s tick seems to survive exclusively on mountain pygmy possums above the snowline, a truly precarious lifestyle. It was for this reason that we realized we were not only dealing with a new species, but a critically endangered one. The tick is on the brink of extinction, as the loss of a significant additional portion its host’s population would likely spell the end.

So clearly Heath’s tick need protection — but why should we save a parasite? you ask. Well, unlike some parasites, Heath’s tick is a rather good neighbor to its host, and surveys have revealed no ill effects caused by it. That’s certainly a good thing for both host and parasite.

Heath’s possum tick is also unique. Its closest genetic relatives live in the highlands of Papua New Guinea, thousands of feet above the tropical lowland forests. This peculiar habitat preference suggests that Heath’s tick and its relatives may descend from a group of relic ticks from the time of the Gondwanan supercontinent, when dinosaurs roamed the Earth and the climate was much cooler and wetter.

So what’s driving this unlikely duo toward extinction? The threat posed by introduced animals is a significant factor. Invasive cats and foxes hunt the vulnerable little possums, and feral horses overgraze mountain plum pines (Podocarpus lawrencei), which the possums partly rely on for shelter and food. Habitat loss is another major threat facing both species: The land they occupy is also ideal for skiing, which sometimes results in land clearing for ski slopes.

The most pressing threat to both species, however, is the danger posed by a warming climate. Both the tick and the possum are highly adapted to snowfall and the cool temperatures afforded to them by mountaintop living. A reduction or complete disappearance of wintertime snowfall could spell disaster for these highly threatened critters.

Fortunately help is at hand for the mountain pygmy possum, and perhaps soon also for Heath’s tick. Conservationists at Zoos Victoria are running a highly successful captive-breeding program for the mountain pygmy possum, and Heath’s tick may soon be added into the program. Such a move would help preserve one of many complex interactions within the Australian alpine ecosystem. Unsurprisingly, ecosystems with more complex interactions are generally more resistant to change, and collapse.

Bringing Heath’s tick into an ex situ conservation program would make it the first such program in the world — something other zoos would also do well to incorporate into future efforts. As we’ve seen with parasites like the Californian condor louse (Colpocephalum californici), not taking the conservation of these tiny passengers into consideration can lead to their extinction by the very scientists tasked with preserving the planet’s rich biodiversity.

For now, though, this new species remains at risk in its threatened alpine habitat. Only time will tell if Heath’s possum tick will survive or if this chance discovery will be both our first and our last glimpse of this remarkable little beast.

The opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Revelator, the Center for Biological Diversity or their employees.

![]()