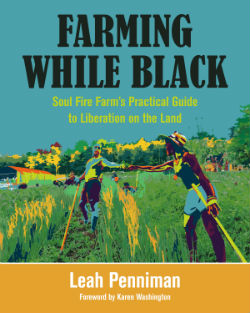

In the introduction to her book Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land (Chelsea Green, 2018), author Leah Penniman quotes Toni Morrison as inspiration: “If there’s a book you really want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.”

So she did.

So she did.

Penniman describes her newly released book as “a reverently compiled manual for African-heritage people ready to reclaim our rightful place of dignified agency in the food system.” The book covers all the practical aspects of building a farm, from finding funding to saving seeds to raising animals. But it’s also a guide to growing community and uprooting racism.

She has put it all to practice as cofounder of Soul Fire Farm, near Albany, N.Y., where she helps grow food and train activist farmers. The farm delivers weekly shares of freshly grown food at sliding-scale prices to families around the region, many of whom live in areas without access to affordable, nutritious groceries.

We talked to Penniman about the ecology and politics of growing food.

What do you love most about being a farmer?

There is so much to love about being a farmer. Today I am in love with the opportunity to be close to the source of all wisdom, which I believe is the living Earth. And by having contact with the soil, there’s abundant communication that comes from the Earth about how we can best live in human community. For example, the mycelium connects the trees and transports sugars and minerals between them, weaving together life across divisions of species and geography. When we have contact with that, I believe that wisdom seeps into our consciousness and helps us know how to better be fully part of the interconnected web of life on Earth.

There is so much to love about being a farmer. Today I am in love with the opportunity to be close to the source of all wisdom, which I believe is the living Earth. And by having contact with the soil, there’s abundant communication that comes from the Earth about how we can best live in human community. For example, the mycelium connects the trees and transports sugars and minerals between them, weaving together life across divisions of species and geography. When we have contact with that, I believe that wisdom seeps into our consciousness and helps us know how to better be fully part of the interconnected web of life on Earth.

What is it about your crops and farming techniques that make them healthier for the soil and planet?

At Soul Fire Farm we use almost exclusively Afro-indigenous farming technologies. Examples of that include semi-permanent raised beds fashioned after the Owambo people in what is now Namibia; the fanya juu terraces that are originally found in Kenya; a polycropping system of trees integrated with herbs and vegetables from Haiti; cover cropping, which George Washington Carver taught us with legumes. We also use animals integrated into our systems in a rotational grazing method that comes out of many places across sub-Saharan Africa. And there are more.

When we got here in 2006 our topsoil was just a few inches deep, with hardpan clay underneath and severely eroded. Since then our soils have more than tripled in depth. We’ve seen the pollinators coming back and a return of biodiversity to the land from these practices.

You write in your book that you initially thought “organic farming was invented by white people” and worried that your “ancestors who fought and died to break away from the land would roll over in their graves to see me stooping.” What did you learn that made you realize that was wrong, and who were the people that inspired the path you’re on now?

It was during a Northeast Organic Farming Association conference as a teen. I’d been farming for a couple years, ready to make it my life’s work, and I was, as you mentioned, feeling disillusioned about the fact that it seemed like a really white community, a white movement. I wondered about my place in it.

I went around and handed out little slips of paper to anyone who appeared Black, Latinx or indigenous to me and asked them to meet. And we shared really common feelings about being one of the few [people of color] in this movement.

Karen Washington was there at the time, who went on to become a farmer at Rise and Root Farm and the founder of the Black Farmers and Urban Gardeners Conference. She said to hang in there — we’re going to claim space in this movement. And that was a turning point for me because it gave me a hypothesis that maybe I didn’t know the whole story.

I started investigating the origins of different sustainable-agriculture techniques and found out that of course everyone from Fannie Lou Hamer to Booker T. Whatley to the Sherrods to the Haitian peasant movement had all made these monumental contributions to sustainable agriculture and sustainable businesses. Those just aren’t talked about in the white-dominated food and land spaces. And so it was time to write a new narrative.

Your work helps to bring food to communities that lack access. What is “food apartheid,” that you reference in the book, and how widespread is it in the United States?

Last I checked there were about 12.5 million people who live in food deserts.

Food apartheid is a concept that Karen Washington taught me. As opposed to a food desert, which you could see as a natural ecosystem and something that has an inevitability to it, food apartheid is more accurate in that it talks about a human-created system of segregation that relegates certain people to food opulence and others to scarcity.

These divisions are often right down the lines of race and very much determined by zip code, which is in turn determined by a history of redlining and the exclusion of people of color from desirable neighborhoods.

What it results in is that black and brown communities are disproportionately impacted by hunger, diabetes, heart disease, obesity and all these other diet-related illnesses. And that is a tragedy for our physical health and it’s also a tragedy for our democracy because folks who are not feeling well cannot participate in civic life.

It’s really incumbent upon all of us to reconsider and reframe how we think of food, not as a privilege reserved for the few, but as a basic human right for all of us.

What can we do as individuals to increase the number of Blacks, Latinx and indigenous people who own land and grow food? What do we need at a policy level to help resource and scale these efforts?

Some of the most important things we can do are to engage in reparations work to fix the harm that’s been done. The land that we stand upon that we farm — it’s stolen land. It rightfully belongs to indigenous people, but it’s been stolen from other communities after that too, including the black community who’s been dispossessed of over 14 million acres of land since 1910. Not through choice, but through legal trickery, through racist violence and through governmental discrimination.

So we really need to look at actually giving that land back and that can be done through a number of channels, like the Land Loss Prevention Project and the Federation of Southern Cooperatives.

I think also at the policy level, we need to look at the way our governmental supports are distributed. Right now they disproportionately benefit row-crop farmers of commodity crops. They benefit corporate farmers and certainly white farmers. We still haven’t remedied that discrepancy in terms of who has access to those resources. And so programs like the 2501 Program [The Outreach and Assistance for Socially Disadvantaged and Veteran Farmers and Ranchers Grant Program] need a complete overhaul and also an increase of funding to make sure that it’s getting to those who need it most.