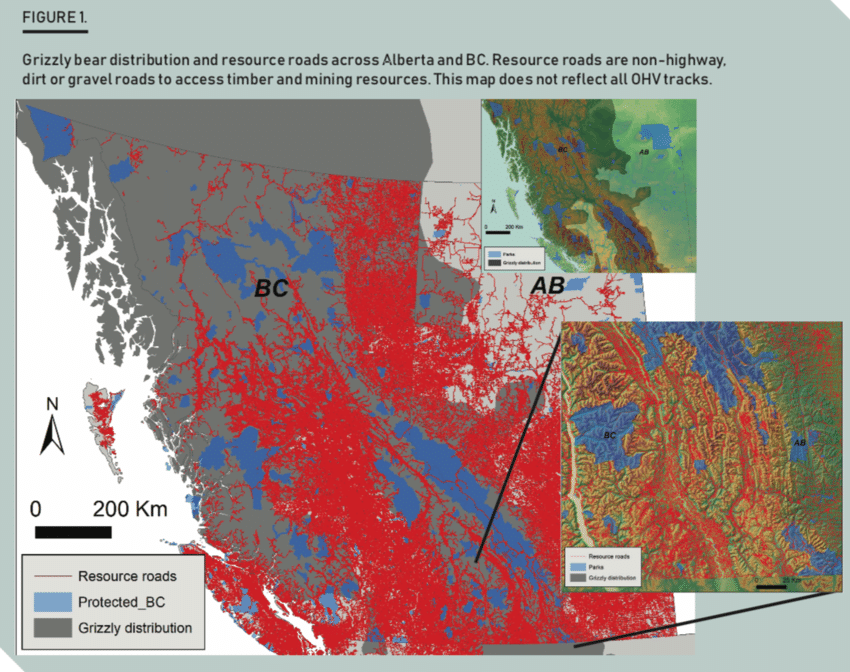

Most people picture western Canada as sprawling, pristine wilderness, with high mountain peaks and thick pine forests as far as the eye can see. But cutting through the woods are hundreds of thousands of miles of resource roads — dirt and gravel roads that provide the public and the timber, oil and mining industries with a thoroughfare into the backcountry. In British Columbia and Alberta alone there are nearly 497,000 miles (800,000 kilometers) of such roads, slicing right through prime grizzly bear range.

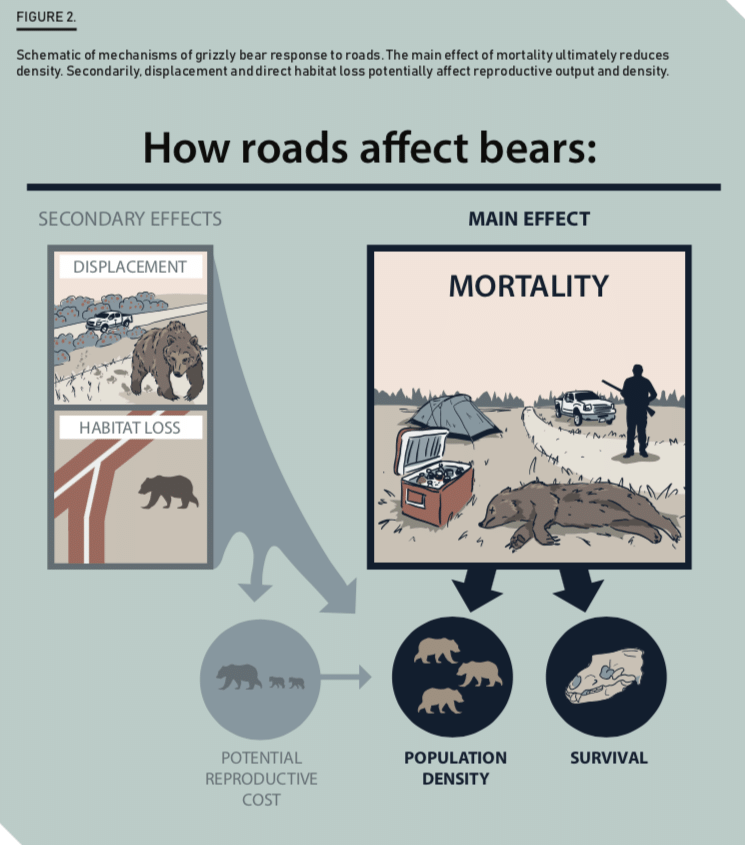

How bad are these roads? A report published last month found that motorized access to wilderness areas is increasingly bad news for grizzly bears, both individuals and populations. When roads are present, grizzlies (Ursus arctos horribilis) die more often.

“Roads have a particularly influential impact on grizzly bears,” says Michael Proctor, an independent Canadian bear research ecologist and co-author of the report. “They also have an impact on elk and mule deer, but grizzly bears are thought to be a decent umbrella species in this region.”

Prior research has found that between 77 and 90 percent of grizzly bears that survive the natural perils of cub-hood will eventually be killed by people — and almost all are killed near roads. This increase in grizzly mortality isn’t due to bears getting hit by vehicles, but rather from conflicts with humans roaming the woods, especially during summer and fall sport- and subsistence-hunting seasons. During these times humans are out looking for deer and elk while bears are foraging nuts and berries to build up their fat supplies ahead of winter hibernation.

“More females have died from ungulate hunters defending their hunt” than have died from the formerly legal grizzly trophy hunt in some areas, explains Proctor, cofounder of the Trans-Border Grizzly Bear Project, which focuses on the conservation of grizzlies in the southern Selkirk and Purcell mountains of British Columbia, Montana and Idaho. “No one wants to get hurt by a grizzly bear, but you put people with guns out in the backcountry and bears die.”

Roads affect bears differently depending on their sex and age. For example, Alberta researchers have found that survival of reproductive-age females declines in areas where road density is greater than about half a mile of road per 250 acres. As females die the local population experiences cascading declines. Exactly how much a population will decline in these areas varies, depending on traffic volume, habitat quality and the tendency of local people to kill bears.

Animals also change the ways they make use of their surroundings in areas where roadways slice through their habitat, leaving populations increasingly fragmented. As a result, bears select smaller home ranges and experience reduced reproduction rates.

The new study ultimately corroborates a report issued last year by the British Columbia’s Auditor General’s office that found habitat degradation was the biggest threat to the province’s remaining 15,000 grizzlies — not trophy hunting, which conservationists had long fingered as the key practice putting bears in jeopardy. Resource roads in the province are increasing at a rate of 6,200 miles (10,000 kilometers) per year, according to the new report. Though British Columbia has far more resource roads than Alberta, it also has far more bears and fewer protections. Grizzlies are a threatened species in Alberta under the provincial Wildlife Act, with fewer than 1,000 left in the wilderness. British Columbia, meanwhile, doesn’t even have provincial protected species legislation, which makes it harder to enact conservation measures. It also means bears rarely come out ahead of industry and development. “British Columbia is a bit further behind in managing access than Alberta,” says Clayton Lamb, a Ph.D. student at the University of Alberta who also worked on the report.

Alberta has already started working on such access management, but British Columbia has made few steps toward protecting the bears. Earlier this month the province announced it would close public access to roads near four key grizzly populations for a few months each year, but the roads will remain open to industry vehicles year-round, and other sites remain unprotected.

The authors ultimately recommend strategically reducing motorized access in both provinces to save grizzlies. “We’re not talking about ‘no roads’ in the backcountry, but a reasonable reduction,” says Proctor. He recommends closing roads in areas where grizzly bear conservation is a concern (like around threatened population groups), in areas where roads occur in high-quality habitats and around areas the provide habitat linkages between populations.

However, wildlife managers have struggled to implement road-access controls that would keep the recreating public out but allow industry in. “It’s universally hard to close a road,” says Proctor. “It was hard in the United States, but the U.S. has adapted.” Because bears have been extirpated in the majority of the lower 48, with no more than 1,000 bears in any of the six remaining population groups, the United States has implemented access controls more swiftly in hopes of protecting the few bears they have left before they disappear. As a cornerstone of recovery, U.S. managers established a motorized-access management system that adjusts road densities based on the security of bear habitat. This includes a requirement for large roadless areas. Canada, with more than 16,000 bears in the West, hasn’t faced such a conservation crunch yet and therefore has been slower to make changes.

On the surface it appears that Canada falls far behind the United States, but Proctor says it’s more that “our problems are finally catching up to us.”

Proctor says the conservation of grizzlies and their habitat on both sides of the border is vital for the species’ long-term survival. Reducing road access goes far beyond regional conservation in Alberta and British Columbia. It would also aid in creating large-scale connectivity between grizzly bear populations across North America. Each patch of habitat is vital to providing a chain between population zones.

This kind of big thinking falls in line with the Yellowstone to Yukon Initiative, a conservation project with the aim of creating a continuous ecological corridor from the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem in Montana, Idaho and Wyoming up to Canada’s Yukon Territory. The corridor spans more than 500,000 square miles — ample room for roaming grizzlies.

Achieving any of these goals requires preserving more habitats with fewer roads. “We need to keep the backcountry core habitat healthy so we have healthy populations to connect,” says Proctor.

© 2018 Gloria Dickie. All rights reserved.