What does it take to save gray wolves in the United States?

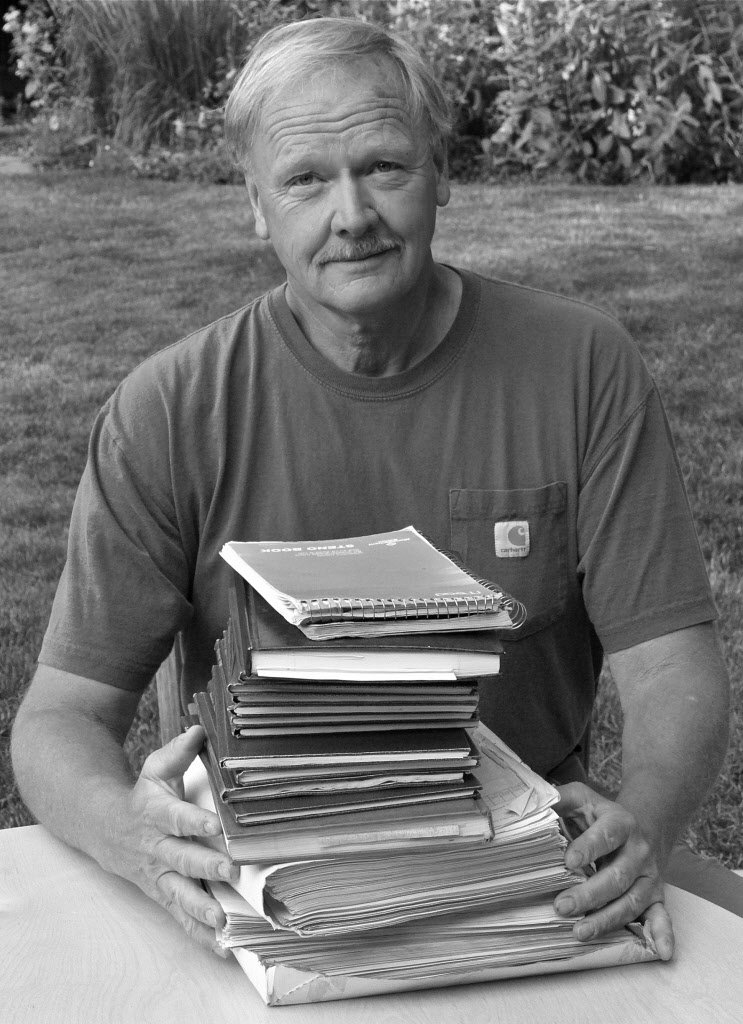

Biologist Carter Niemeyer has spent more than three decades trying to answer that question. A former federal wildlife trapper, he was instrumental in the effort to return wolves to Yellowstone National Park in 1995. Later he coordinated the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s efforts to recover wolves in Idaho. Through all of this, he also studied wolves and their interactions with livestock, helping to dispel the myths that all too often turn ranchers and the public against these highly social and intelligent predators.

Now retired from the Service, Niemeyer — author of the memoirs Wolfer and Wolf Land — still devotes his life to wolf conservation. A frequent lecturer, he advocates for finding the middle ground where both wolves and humans can coexist on the landscape.

Now retired from the Service, Niemeyer — author of the memoirs Wolfer and Wolf Land — still devotes his life to wolf conservation. A frequent lecturer, he advocates for finding the middle ground where both wolves and humans can coexist on the landscape.

At a time when the federal government is once again considering taking wolves off of the endangered species list, we spoke with Niemeyer about what it takes to allow the predators to thrive and how we can dispel the myths that slow efforts to restore their populations.

Your own journey took you from wolf trapper to rescuer. Is there anything in your experience that could help others make a similar transition, for wolves or other species?

To understand and appreciate wolves you have to learn the truth about them — scientific truth — and put aside anecdotes and stories that are obviously conceived in fear, hate and resentment. Studying and watching wolves can teach people a lot about the animal. The fact is that wolves are shy predators that help wild prey populations remain healthy and sustainable. If people find room in their heart for wolves, then they can fully appreciate the benefits of maintaining wolves in abundance.

How do you feel about the continued expansion of wolf range? Are you satisfied, or is there still much further to go?

I’m encouraged by the way wolves have dispersed out of the core recovery areas in Idaho, Montana and Wyoming. Wolf numbers also continue to grow in Washington and Oregon, and recolonization may be under way in parts of Northern California. I think public education about wolves should be a top priority.

You’ve done a lot of work on the interactions between wolves and livestock. What’s the hardest thing to overcome at this point?

People working together can reduce predation by wolves on livestock, but the reality is that some livestock damage will always occur. That’s frustrating, because I want wolves to stay out of trouble. Wolves are predators that depend on large wild prey like deer, elk, moose, caribou and bison for food. In the absence of abundant prey, wolves are sometimes forced to kill livestock, and this can really create emotionally charged situations. It often results in hate and animosity toward wolves. Having been intimately involved with this over the years, I believe that awareness of wolf presence and better animal husbandry practices can minimize problems between wolves and livestock.

The on-again, off-again Endangered Species Act protection for wolves must get frustrating. How do you feel that will ultimately pan out?

The Endangered Species Act was really the only way to proceed with recovery because it guaranteed the highest protections for wolves while recovery was in progress. That protection ultimately resulted in viable, sustainable wolf populations. I think a lot people mistake an ESA listing as a permanent state of affairs, but it was never meant to function that way. Other regions that fall outside of ESA recovery areas, like Colorado, still need more time for wolf numbers to increase, and I think they will.

Wolves are prolific and resilient and I believe they will ultimately succeed in most areas where basic habitat needs, open space and abundant prey are all available — and all of this can happen even without ESA protection.

Is there anything that your average environmentalist or advocate tends to get wrong about wolves?

Wolves aren’t saints. They aren’t sinners, either. They’re just being wolves. I think people who put them on a pedestal are setting themselves up for a fall.

Also, though wolves are habitat generalists and can live almost anywhere, there are many regions of the U.S. where they will never be because there are too many people and too much livestock. Wolf advocates must first support public lands and wild places that reduce the interface between wolves and people. Wolves can only survive where human tolerance allows them to thrive.

Related Stories:

The Ethics of Saving Wolves