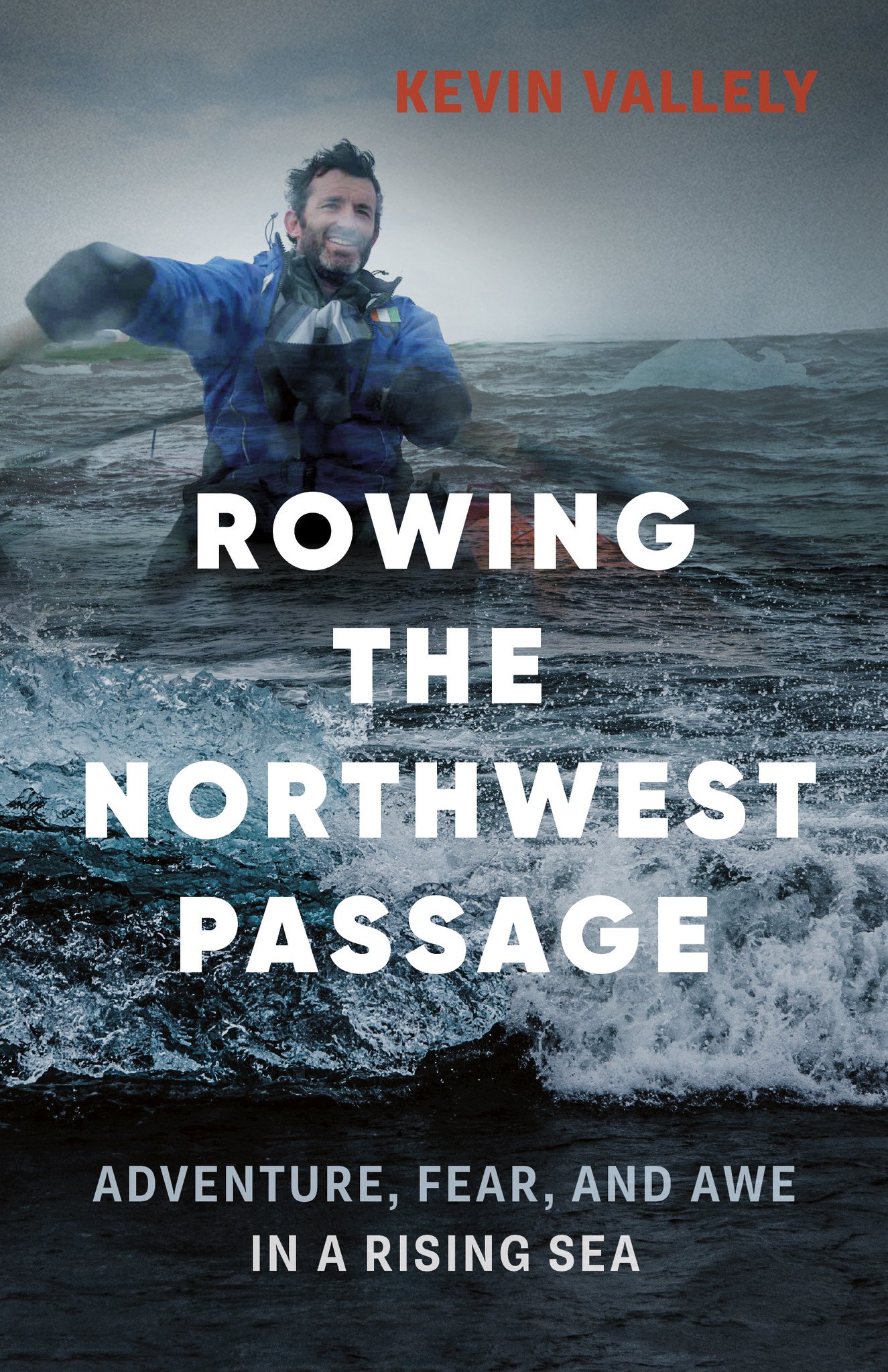

In 2013 four adventurers set out on an 80-day rowboat mission through the Arctic’s rapidly melting Northwest Passage. Their journey brought them face to face with the changing seas in a world of climate change. In this excerpt from adventurer Kevin Vallely’s new book about the expedition, Rowing the Northwest Passage (Greystone Books), we also see how climate change has affected some of the people the team met along their journey:

An elderly woman walks toward us from the road. Tuktoyaktuk, in the Northwest Territories, is a sizable town by Arctic standards, with a full-time population of 954, but it’s small enough that the bulk of the town likely knows we’re here. The woman is smiling when she reaches us.

“I saw you coming in,” she says. “Where you guys come from?” “We’re from Vancouver,” I say, my mouth still half full of food. “We started our trip in Inuvik nine days ago.” Her name is Eileen Jacobsen and she’s an Elder in town. She and her husband, Billy, run a sightseeing business. “You should come up to the house in the morning and have some coffee,” she tells us.

Our night’s sleep in the Arctic Joule is fitful; our overindulgence runs through all of us like a thunderstorm. By seven in the morning, even with both hatches open, lighting a match in the cabin would blow us out like dirt from that Siberian crater. The roar of the Jetboil pulls me out. Frank’s already up, down jacket on, preparing coffee. “You like a cup?”

Our night’s sleep in the Arctic Joule is fitful; our overindulgence runs through all of us like a thunderstorm. By seven in the morning, even with both hatches open, lighting a match in the cabin would blow us out like dirt from that Siberian crater. The roar of the Jetboil pulls me out. Frank’s already up, down jacket on, preparing coffee. “You like a cup?”

It’s still too early to drop by Eileen Jacobsen’s house, so we walk into town on the dusty main road, our ears assaulted by a cacophony of barking dogs. Dirt is the surface of choice for roads and runways in Arctic communities, as any inflexible surface like concrete would be shredded by the annual freeze–thaw cycle. Most of the town runs the length of a thin finger of land, with the ocean on one side and a protected bay on the other. About halfway down the peninsula, a cluster of wooden crosses rests in a high grass clearing, facing west. We heard about this graveyard in Inuvik. Because of melting permafrost and wave action, it’s eroding into the sea, and community members have lined the shore with large rocks to forestall its demise. This entire peninsula will face this threat in the coming years. There’s not much land here to hold back a hungry ocean.

We notice an elderly man in a blue winter jacket staring at us a short distance away. He’s sitting outside a small wooden house and smiles as we approach. “You guys must be the rowers,” he says. “Too windy to be out rowing.” His jacket hood is pulled tight over his ball cap and he dons a pair of wraparound shades with yellow lenses that would better suit a racing cyclist than a village Elder. His name is Fred Wolki, and he’s lived in Tuk for the last fifty years. “I grew up on my father’s boat until they sent me to school in 1944, then I came here.”

His father, Jim Wolki, is a well-known fox trapper who transported his pelts from Banks Island to Herschel Island aboard his ship the North Star of Herschel Island. Interestingly, we had the Arctic Joule moored right beside the North Star at the Vancouver Maritime Museum before we left. Built in San Francisco in 1935, the North Star plied the waters of the Beaufort Sea for over thirty years, her presence in Arctic waters playing an important role in bolstering Canadian Arctic sovereignty through the Cold War.

“We’re curious if things have changed much here since you were a boy,” Frank says.

“Well…it’s getting warmer now,” Fred says, shaking his head. He gestures out to the water speaking slowly and pausing for long moments between thoughts. “Right up to the 1960s…there was old ice along the coast… The ice barely moved… It was grounded along the coastline.” He looks out over the shoreline, moving his arm back and forth. “They started to fade away slowly in the 1960s… icebergs… They were huge, like big islands… They were so high, like the land at the dew Line station… over there.” He points to the radar dome of the long decommissioned Distant Early Warning Line station that sits on a rise of land just east of us. “It’s been twenty years since we’ve seen one in Tuk.” There’s no sentimentality or anger in Fred’s voice; he’s just telling us his story. “It’s getting warmer now… Global warming is starting to take its toll… All the permafrost is starting to melt… Water is starting to eat away our land.”

I listen to his words, amazed. There’s no agenda here, no vested interest, no job creation or moneymaking — just an elderly man bearing witness to his changing world.

Excerpted from Rowing the Northwest Passage: Adventure, Fear, and Awe in a Rising Sea by Kevin Vallely, published September 2017 by Greystone Books. Condensed and reproduced with permission from the publisher.