It’s market day in Bisil, in southwest Kenya, about 37 miles (60 kilometers) from the border with Tanzania. People from the surrounding countryside have brought their animals for trade.

This market is supposed to be for cattle, goats, and sheep, but today hundreds of donkeys dominate the grounds — “including foals and pregnant mares,” says Wiebke Plasse of the German animal welfare group Welttierschutzgesellschaft, who visited the market to investigate the condition of Africa’s donkey population.

On the road into town, she and her Kenyan contacts had already seen massive herds of donkeys. Several hundred animals were present, with more still on their way, one trader told her.

And why so many? “When you ask, you find out: All these donkeys are reserved for a single buyer, who isn’t even here,” Plasse says.

Plasse learned that the donkeys had reached the market by mixed routes — some legally purchased, many stolen.

Regardless of how they were obtained, all were handed over to a single buyer, and their fate was likely illegal slaughter outside licensed abattoirs, often in brutal and unhygienic conditions, their hides stripped with knives and prepared for export.

Kenya shut down all licensed donkey slaughterhouses in 2020 after public outcry. But the trade in hides — impossible to acquire without killing the animals, of course — has not stopped. Donkeys are now killed in illegal backyard sites, and their hides continue to leave the country, often mis-declared under the generic customs category of “animal skins.”

Plasse recounted meeting a boy of perhaps 10 years old who told her his father had just sold the family’s only donkey to pay his school fees.

That’s a typical story in a region losing its donkeys, says Solomon Onyango, Kenya country director for an animal-welfare nonprofit called The Donkey Sanctuary.

“The trade in donkey skins is driving up prices in Kenya and across Africa,” he says.

That inflation has a double effect: Families already living on the brink are sometimes persuaded to sell their donkeys for urgent needs such as school fees — but once the animal is gone, the higher prices make it almost impossible to buy another. In either case, the result is the same: the long-term loss of a livelihood and of what Onyango calls “the silent backbone of everyday life. Many families can’t afford to replace an animal once it’s been sold or stolen.”

Between 2016 and 2019, Kenya lost about half its donkeys, whose numbers plummeted from roughly 1.8 million to fewer than a million. Prices more than doubled — from about $50 to $115 — while the average monthly income hovers around $55.

More Than a Beast of Burden

“This means a long-term loss of livelihoods,” Onyango adds. In many communities donkeys are the quiet backbone of everyday life — carrying clean water and firewood, taking children to school, mothers to clinics, and goods to market.

A single donkey can save a woman five hours of heavy labor each week, and twice that for a child.

According to a 2024 report, these animals underpin the existence of some 158 million people in Africa — a partnership stretching back 5,000 years, when the first Equus asinus were domesticated in East Africa.

Now their proud lineage often ends as a dried hide in a shipping container bound for China.

A Growing Market

Once they reach Asia, a multibillion-dollar market awaits.

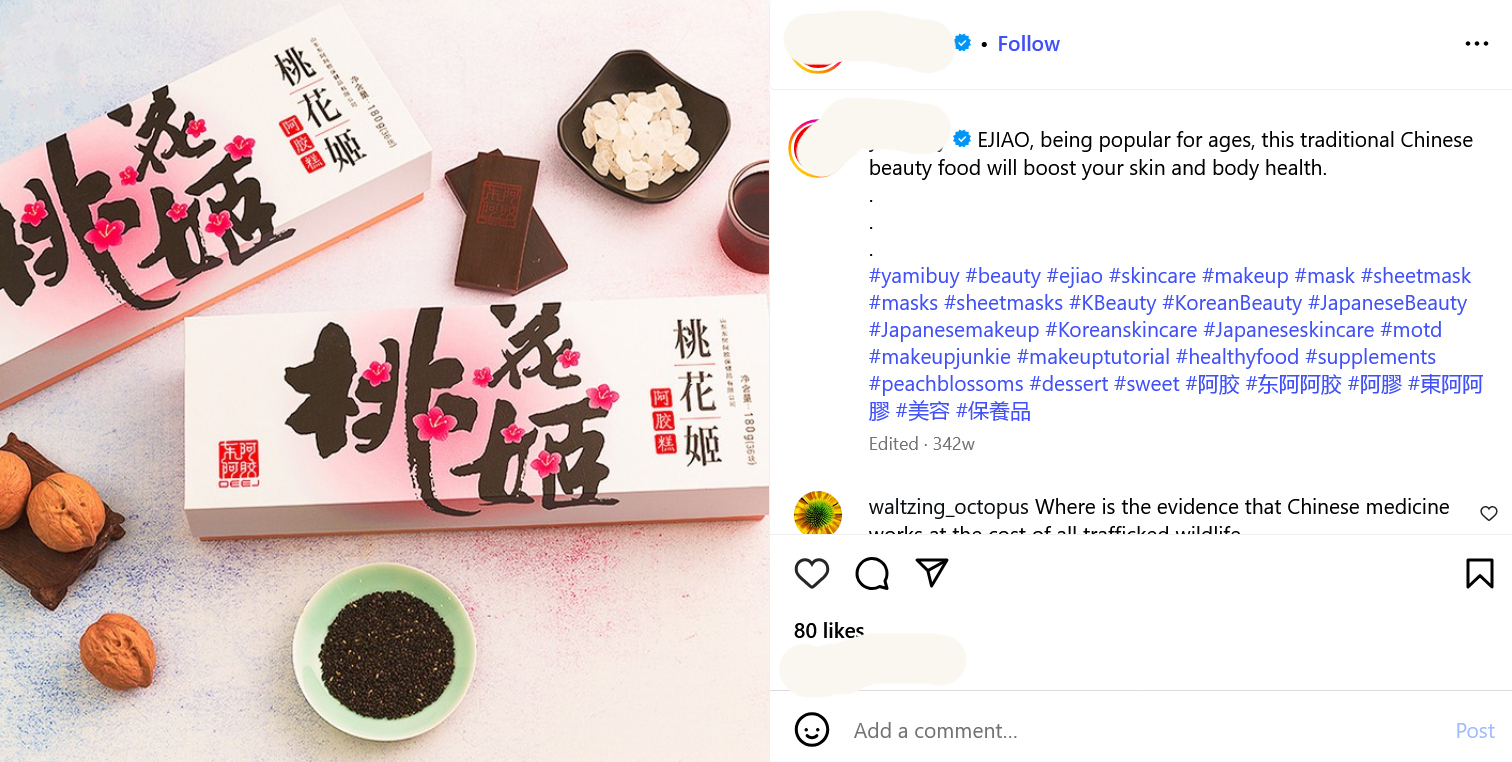

Factories in China — mainly in Shandong Province — boil down the hides into gelatin known as ejiao, which is used in traditional Chinese medicine as a purported remedy for anemia, insomnia, and aging. Its reputation dates back to imperial times, but modern demand is driven less by tradition than by modern-day marketing, which has repositioned it as a lifestyle product. In one popular TV drama, imperial concubines consumed it daily to stay beautiful and fertile, and sellers promote it as a luxury gift or a beauty tonic. It’s even reimbursable through health insurance.

The collagen is extracted by simmering the hides for hours. Practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine regard the skin’s dense fiber structure as especially suitable for ejiao production — soft, elastic, yet structurally strong, qualities seen in Chinese medicine as energetically valuable.

Lauren Johnston, associate professor at the University of Sydney China Studies Centre, says this specificity is why donkeys can’t be easily substituted and why people in Africa are suffering as donkeys disappear: “The ejiao industry is blind to the situation in Africa. They just want donkeys.”

According to The Donkey Sanctuary and the University of Reading, the industry’s estimated demand in 2021 was around 5.9 million hides annually and is projected to rise to 6.8 million by 2027. Meanwhile China’s own donkey population has collapsed since the 1990s — from 11 million to about 1.46 million — forcing the market to turn global.

Africa, home to roughly two-thirds of the world’s remaining 50 million donkeys, has become the main supplier. A shipping container full of hides can yield several tons of gelatin.

Unlike wildlife products such as tiger bone, pangolin scales, or rhino horn, donkey hides come from domesticated livestock and therefore are not covered by the protections of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, a treaty that covers the cross-border commerce of threatened animals and plants. In many countries there’s no specific legal basis for blocking shipments.

“This is a legal gray area,” says Janneke Merkx, campaigns manager at The Donkey Sanctuary. “Donkey hides are typically shipped under generic categories, making them hard to trace.” As a result, she says, the trade is lucrative and relatively easy to source from Africa: “It’s seen as low risk precisely because the legal status is unclear or unchallenged.”

The real problem starts where industrial demand meets biological reality: Donkeys reproduce slowly — mothers gestate a single foal at a time, with pregnancies lasting a year or more — and can’t be farmed at the speed of pigs or chickens.

This is where the arithmetic of extinction begins.

The Limits of Farming Donkeys

Agricultural economist Simone Pfuderer of the University of Reading is one of the few researchers to have run the numbers on the donkey hide trade. In a 2020 study, she examined whether the ejiao industry’s growing demand could realistically be met through controlled breeding operations.

“We have modeled scenarios in which the system scales up to a demand of 5 million hides per year,” Pfuderer explains. Even in the best case, such a production cycle would require a fully established breeding population of around 15 million donkeys, including at least 5 million breeding females. Building up that herd would take a minimum of 14 years — “assuming everything runs optimally,” says Pfuderer.

But nothing suggests that this buildup has even begun in a way that could succeed.

On the contrary, China’s donkey population has continued to shrink.

In the meantime Africa remains the main supplier. But the arithmetic of supply and demand does not work in its favor. In South Africa donkey numbers have dropped by 30% since 1996. In Ghana women interviewed by British social scientist Heather Maggs of the University of Reading for a study feared that donkeys could vanish from the country in under five years.

“If the exploitation of donkeys here in Kenya continues at this rate, they could be endangered between 2027 and 2030 — just like rhinos or elephants,” warns Solomon Onyango.

The Broader Impact Across Africa

The loss of donkeys would be felt across the continent.

Maggs’ study found that owning a donkey strongly correlates with a household’s economic standing.

“Poor people own donkeys in order to survive,” she explains. “But those without donkeys are the poorest of the poor.”

In families without donkeys, a woman must carry water or firewood herself — often up to two headloads of 60-plus pounds (or 30 kilograms) each over an average of 3 miles (5 kilometers) per day.

Theft, incentivized by the hide trade, has intensified the hardship: “More than half of donkey owners and even people without donkeys told me they had personally experienced livestock theft,” says Maggs.

This pushes families deeper into poverty and strains their children physically and in daily life. Girls from households without donkeys are often tasked with heavy water and firewood loads, leaving them more prone to back and neck injuries. And because they spend more time on labor-intensive chores, they have less time for school and study.

Political Response and the African Union Ban

African leaders have begun to recognize this ticking social time bomb in their rural regions. In February 2024 the African Union took a strong stance: The slaughter of donkeys for hide exports is to be banned across the continent for 15 years. The resolution now needs to be implemented by each member state through national laws. The African Union also announced plans for a continent-wide protection framework for working donkeys.

“This is a strong symbol — the AU is saying to a powerful partner like China: This stops here,” says Wiebke Plasse.

Johnston notes that the decision caught Beijing off guard, putting China in a dilemma: “Its ejiao demand directly undermines its stated development goals in Africa. If China’s demand pulls this animal out of the equation,” she says, “it harms poverty reduction — a goal China says it wants to promote in Africa.”

Enforcement Challenges and Criminal Networks

But is the ban enforceable? Merkx believes it could be, but only if countries pass their own laws and back them up with staff, inspections, and political will.

Change on a large scale, she warns, does not happen overnight. Animal welfare groups caution that the ban can only be a first step: Criminal networks quickly adapt to restrictions and exploit loopholes, so enforcement must stay one step ahead.

The announcement of the ban triggered an immediate reaction from traffickers. Donkey thefts increased, hide trading activity spiked, and a sense of “last chance” profiteering spread before national laws could take effect.

Kenya’s licensed donkey slaughterhouses were shut down in 2020 after public outcry. But Plasse reports from her Kenya visit that even when those facilities were still open, they were already processing stolen donkeys. “These existing networks have, to our knowledge, regained full momentum.’”

Wildlife Crime and Biosecurity Risks

The donkey-hide trade’s legal grey area also makes it a convenient cover for other illicit wildlife and animal products.

Economist Ewan Macdonald of the University of Oxford has documented these overlaps: “If you buy donkey hides online, you will almost inevitably find illegal products for sale alongside them — like pangolin scales or ivory,” he says. And that’s on open e-commerce and social media platforms, not just hidden markets, the study found.

Nearly a fifth of online donkey-hide sellers also offered other wildlife goods, often involving species protected under CITES. Donkey hides and wildlife products often come from the same African sources and use the same transportation routes. Traders sometimes bundle them at the slaughter stage, either because customers want both or to use donkey hides as a cover for more valuable contraband.

Such informal trade routes and improvised slaughter sites also pose disease risks. Where multiple species are slaughtered and transported without veterinary oversight, the chances of new diseases emerging — in animals and humans — rise sharply. Nigerian veterinarian Ibrahim Ado Shehu, West Africa representative of the Commonwealth Veterinary Association, notes that 75% of infectious diseases in humans originate from animals, known as zoonosis.

“These pathogens do not only come from wildlife — domestic and farm animals can also be carriers,” Shehu says. “The entire global process of animal production, transport, slaughter, and use is a ticking time bomb.” Examples include anthrax, MERS, SARS, Ebola, rabies, and, most recently, COVID-19.

“If we want to avoid future pandemics, we must rethink how we treat and use animals,” says Shehu. The donkey hide trade, he warns, needs urgent scrutiny.

Human Cost and Daily Realities

But people in Africa, for instance in poorer neighborhoods of Nairobi, hear little about international trade debates, wildlife crime, or zoonotic diseases.

What they see instead is the tangible shortage — and the silent overwork of the few animals that remain.

Plasse’s fact-finding trip on donkey hides ended in one such Nairobi suburb. She recalls the “painful impressions” and a final meeting with a donkey named Kamba, whose owners rent him out to strangers day after day.

“Kamba is old and frail, his body worn down by years of carrying loads — he’s blind, walks slowly, and limps.” Yet he is one of the last donkeys still securing access to water, hauling jerrycans along dusty paths for people he doesn’t even know.

“These last rental animals work without rest,” Plasse says. The fewer donkeys in a community, the greater the burden on those who remain.

Seeking Solutions

What can be done? The African Union’s ban is a strong signal, experts say.

But global responsibility also lies with the demand side. Animal welfare advocates urge the ejiao industry to invest in humane alternatives.

Research has already shown potential: “In the field of cellular agriculture, it’s already possible to produce collagen in the lab — clean, sustainable, and animal‑free,” says Merkx.

Yet such solutions are far from implementation and time is running out for Africa’s people. The extinction of their donkeys is looming.

Even Kamba will not haul water, food, and people through Nairobi’s outskirts forever. When he is gone, will his owners still be able to replace him? Or does Kamba already belong to the last generation of donkeys in Kenya — perhaps in all of Africa?

Previously in The Revelator:

The Exotic Pet Trade Harms Animals and Humans. The European Union Is Studying a Potential Solution