ISLAND PARK, Idaho – From the top of 9,898-foot Sawtell Peak, just outside the western boundary of Yellowstone National Park, I imagined I was a young male grizzly bear on the move, seeking new territory beyond the park’s safety.

Grizzlies (Ursus arctos horribilis) — powerful and omnivorous — are able travelers and often on the lookout for new habitats. That’s especially true for younger bears, which must disperse and find their own personal territories away from established, ornery, solitary males, which are known to kill cubs.

Dispersing grizzlies which happen to wander beyond the national park, where hunting is prohibited, must run a gauntlet of human dangers: highways, tempting-but-deadly garbage piles, tasty and easy prey such as sheep and, most of all, people, whose first instinct oftentimes is to reach for a gun, a trap or a poison.

The essential question becomes: How do grizzlies, which were nearly wiped out in the Yellowstone region and most of their historic range in the lower 48 states more than a century ago, naturally expand their current range and grow their numbers so that extinction is no longer a threat?

It’s not theoretical. A few weeks ago the Trump administration took Yellowstone’s grizzlies off the endangered species list, renewing questions about how — and whether — these bears will ever connect with other grizzly populations in the northern Rocky Mountains. In the long run, bear experts say, that connectivity will be critical to a healthy population of bears in the lower 48.

Conservation organizations and academic biologists support this natural dispersion and connectivity, where grizzlies could move through protected corridors across a vast landscape and find other grizzly populations. There, they can mix their genes and improve their odds to survive as a species.

On the other hand, state and federal government wildlife managers support an approach where isolated populations of grizzly bears are confined to within highly controlled “Demographic Monitoring Areas” that limit natural connectivity to reduce the bears’ impact on human activities. If and when the grizzlies need a genetic boost to secure their long-term survival, breeding animals can be translocated from one location to another.

The long-term fate of about 700 world-famous Yellowstone grizzlies and about 1,100 other grizzly scattered across pockets in the Northern Rockies — and the fate of how the Endangered Species Act will be implemented in the future, particularly when it comes large, wide-ranging predators such as grizzlies and wolves — hinges on which management approach is ultimately adopted.

The grizzly bear is the oblivious star in a high-stakes legal and political battle that is now unfolding that will determine how and where grizzlies will share the upper Rocky Mountain landscape with human beings.

From my perch on Sawtell, I had a grand view of a fork in the grizzly trail, one that is fraught with danger — and the other with a fragile promise of unclaimed territory.

To the south lies the resort community of Island Park, where the summer population swells to more than 10,000 as visitors flock to summer homes, RV parks, cattle ranches and campgrounds scattered throughout the Caribou-Targhee National Forest. U.S. Highway 20 bisects the community. Its 70-mile per hour speed limit and heavy truck traffic pose a significant obstacle for a young grizzly in search of new turf.

If a bear meanders through Island Park, it risks creating a ruckus by delving into garbage cans, ripping down bird feeders, munching on dog food or preying on livestock — all actions that could attract attention from wildlife managers who could decide to take lethal action on the “problem” animal. Even if the bear escapes that gauntlet and heads to the southwest, it will descend into a valley filled with hostile farmers — a certain dead end.

But if a grizzly heads northwest towards Henry’s Lake at the base of Sawtell Peak, and manages to avoid a couple of campgrounds and ever-encroaching subdivisions, and ascends into the Centennial Mountains that cut to the west, it has a chance to roam far and wide and help recolonize long-lost habitat.

Grizzlies on the Move

Despite the formidable obstacles, Yellowstone grizzly bears are steadily expanding their range, often using the Centennial Mountains as a springboard to the west and to the north. Yellowstone grizzlies are now found throughout the Gravelley and Snowcrest ranges north of the Centennials.*

Meanwhile, the same grizzly dispersion dance is occurring 370 miles north, where another population based in and around Glacier National Park is also steadily expanding. The Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem of grizzly bears numbers about 960 and they are dispersing down river valleys and across mountain ranges. Intrepid young males range far and wide, making headlines in community newspapers.

“There are places throughout the ecosystems where bears probably haven’t been for over 100 years,” says Frank van Manen, a U.S. Geological Survey wildlife biologist and the supervisory research biologist for the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, which conducts research on grizzlies and monitors their populations and death rates.

The gap between dispersers from the two grizzly populations is steadily narrowing. Wildlife biologists hope that Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem grizzlies, which have a strong genetic base supported by breeding with grizzly populations in Canada, will connect and breed with the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem grizzlies, which have been isolated for more than 100 years.

“I think we are probably less than a decade away from that if the populations keep expanding like they have been,” van Manen says during an interview in his office near the Montana State University campus in Bozeman. “The edges of the distribution are now only separated by about 70 miles and that’s close to striking distance of a dispersing male. So we’re pretty close.”

One or more grizzlies dispersing possibly from the Northern Continental Divide population were sighted last year in the Upper Big Hole River Valley.

Caroline Byrd, executive director of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, a Bozeman-based grizzly bear advocacy group that works to reduce conflicts between bears and humans, puts the distance between to the two populations at only 40 miles.

“There’s a lot of open habitat where there’s room for bears to expand and move through,” she says.

Allowing the Yellowstone and Northern Continental Divide populations — which have been separated for more than 100 years after grizzlies were hunted to the brink of extinction in the lower 48 — to naturally reconnect and interbreed would mark a monumental success for the Endangered Species Act, wildlife biologists and conservation groups say.

“I would consider it a victory for the Endangered Species Act, and a major stepping stone toward (grizzly bear) recovery,” says Dr. Jeremy Bruskotter, an associate professor at Ohio State University’s School of Environment and Natural Resources, whose extensive writings about the Endangered Species Act include an in-depth examination of how to define what part of a species’ range is protected.

“Eventual connectivity between populations would be a tremendous achievement,” adds Erin Edge from Defenders of Wildlife.

But that natural connectivity may never happen.

Feds Remove ESA Protections

The Trump Administration’s July 30 removal of the Yellowstone grizzly bear population from the endangered species list — a process begun years earlier under the Obama administration — sets up new barriers for natural grizzly connectivity. Conservationists and academic experts say it is another in a series of steps by the government to reduce the size of habitat considered necessary to recover threatened and endangered species.

The decision turns over management of Yellowstone grizzlies to Wyoming, Idaho and Montana, which all plan to institute regulated trophy hunting on the perimeter of Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks. If state wildlife managers institute a hunt this year, which is currently considered unlikely, up to 20 bears could be legally shot. (See our story, “Yellowstone Grizzlies: How Many Could Hunters Kill?”)

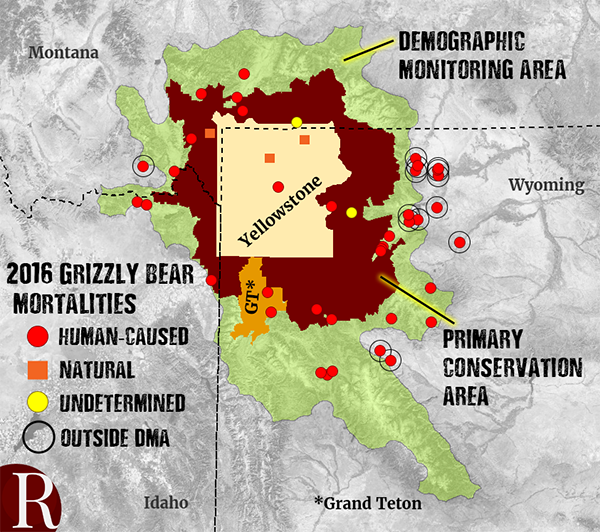

Trophy hunting has generated a firestorm of protest, despite the relatively low number of bears that could legally be hunted based on 2016 population and death rates. A potential bear hunt would impact fewer than the 23 grizzlies killed in 2016 by wildlife managers because of livestock conflicts. Last year, a total of 58 bears are known to have died, most of which from conflicts with humans. Eleven bear deaths are under criminal investigation possibly related to poaching.

Van Manen doesn’t believe trophy hunting will have any impact on maintaining a stable Yellowstone grizzly population. The study team has set overall mortality rates for independent male and female bears that are designed to keep the long-term population stable at about 674 bears. If the Yellowstone grizzly population falls below 600, no hunting will be allowed; culling would be reserved in the case of risk to human life. But the number of bears could fall as low as 500 before revisions would be required to a grizzly conservation plan signed by the states.

Van Manen doesn’t believe trophy hunting will have any impact on maintaining a stable Yellowstone grizzly population. The study team has set overall mortality rates for independent male and female bears that are designed to keep the long-term population stable at about 674 bears. If the Yellowstone grizzly population falls below 600, no hunting will be allowed; culling would be reserved in the case of risk to human life. But the number of bears could fall as low as 500 before revisions would be required to a grizzly conservation plan signed by the states.

“The way I look at it as a scientist is that the hunting mortality is just one other form of mortality,” van Manen says. “Whether managers remove an animal or whether it actually gets killed by a hunter, is very different in terms of how society might look at that, but in terms of the number-crunching, it’s really the same thing for us.”

Academic researchers who study large carnivores say resuming any hunting on a species just removed from the endangered species list — especially a predator such as grizzlies, which has one of the lowest reproductive rates of all terrestrial mammals — makes no sense.

“Why did we spend all of this money to just get them beyond the threshold where they can kind of sustain themselves only to risk pushing them back down by hunting?” says Dr. Brad Bergstrom, a biology professor at Valdosta State University and an expert on large carnivores.

“Would you consider doing that to the bald eagle?” he asks. “Start shooting them immediately after taking them off the endangered list? It’s absurd. To me it just violates the spirit of the law.”

Ring of Fire

The furor over grizzly trophy hunting has overshadowed an even greater institutionalized risk to the bears in the West.

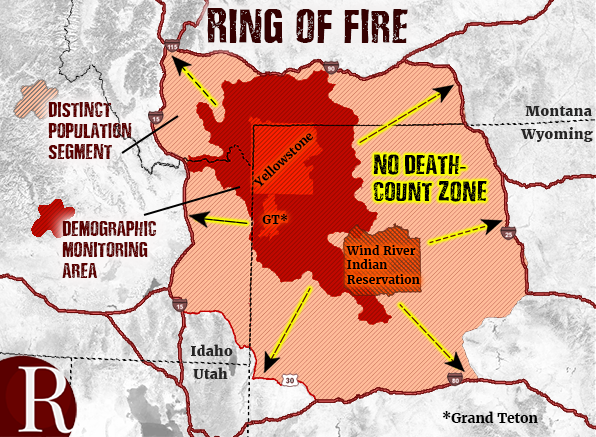

The federal management plan laid out in a 131-page rule creates a second perimeter beyond the state-managed hunting zones where the deaths of grizzlies that move into this area and die, for any reason, will not be measured as part of the overall Yellowstone population.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has determined that bears dispersing from the 16,000 square mile “Demographic Monitoring Area” that surrounds Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks and adjacent national forests, wilderness areas and an Indian reservation are “not biologically necessary” to maintain the Yellowstone population.

The grizzly bears recently sighted in the Upper Big Hole River Valley that could provide the long-awaited genetic connectivity between the Yellowstone and Northern Continental Divide populations are included in the no death-count zone.

These potential deaths are important because they will understate overall grizzly deaths and not be included in a federal formula to determine hunting quotas within the Demographic Monitoring Area that is designed to maintain a long-term stable Yellowstone grizzly population.

Bears that disperse outside the Demographic Monitoring Area but within the much larger Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem now fall solely under state jurisdiction and the states can set whatever hunting quota they wish. If a dispersing grizzly manages to get beyond the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem boundary, it once again falls under Endangered Species Act protections, for now.

A Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks spokeswoman says the state plans to take a “very conservative” approach to hunting in the area outside with Demographic Monitoring Boundary and within the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. The state recognizes the importance of connectivity between the Yellowstone and Northern Continental Divide ecosystems, but its stated goal is to manage grizzly bears as a game species and “allow for grizzly populations in areas that are biologically suitable and socially acceptable.”

No definitive grizzly hunting plans have been released.

Dr. David Mattson, a leading expert and former member of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, says bears found outside the Demographic Monitoring Area will fall into a “free-fire zone” that could create a death trap for dispersing grizzlies.

This “will almost certainly reduce the odds of connectivity that would have otherwise likely happened with (Endangered Species Act) protections,” he says.

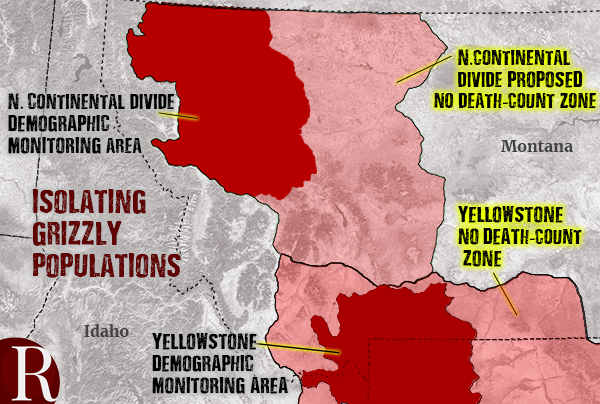

The Fish and Wildlife Service appears to be following a similar approach of creating a no death-count zone around the Northern Continental Divide population when the agency removes that population from the Endangered Species Act, which it intends to do.

According to the 2013 Montana grizzly management plan, if a no death-count zone is created around Northern Continental Divide Demographic Monitoring Area, it would border the Yellowstone no death-count zone. Taken together this would create a vast area between the two largest core populations of grizzlies in the lower 48 where grizzly deaths would not be counted and hunting would be controlled by Montana with no federal oversight.

Cattle ranches dominate the rural economies in the region between the Yellowstone and Northern Continental Divide ecosystems where bear deaths wouldn’t be counted if the Fish and Wildlife Service follows the same delisting plan with the Northern Continental Divide population as it has done with Yellowstone.

“I guarantee you that grizzly bears are not going to stop depredating on cattle,” Mattson says. “It’s not likely they are no longer going to be a problem for ranchers, like getting into garbage. I guarantee you that the more likely response, even now, in the states is going to be to kill bears and most of those conflicts are going to be concentrated on the periphery.

“Bears that maybe were being given a path before (under Endangered Species Act protections), will not have that any longer,” he predicts.

The Long Road to Recovery

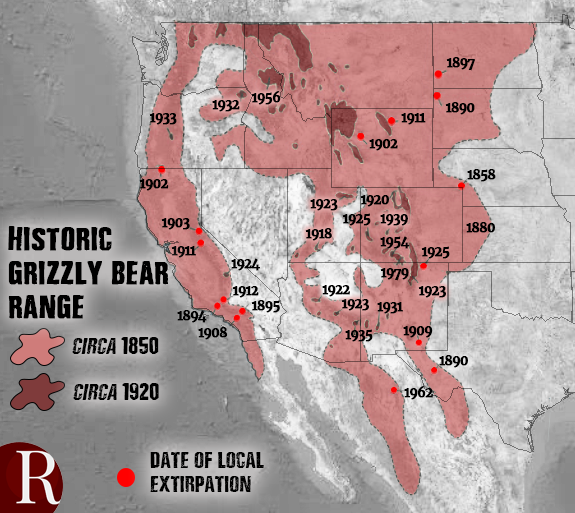

There were once an estimated 50,000 grizzly bears in the western half of the contiguous United States. As European settlements spread across the West, most of the animals were shot, trapped or poisoned — the victims of the same kind of hostility that confronted wolves, mountain lions and other large carnivores. Grizzlies in the West had been pushed back into a few pockets in the Northern Rockies that constitute less than 4 percent of their former range.

By the time the isolated Yellowstone grizzly population was protected under the Endangered Species Act in 1975, there were as few as 136 bears. The Yellowstone population had been sharply reduced after open-pit garbage dumps that were favorite grizzly feedings grounds were closed in Yellowstone. After they were protected the Yellowstone grizzly population steadily expanded throughout the 1980s and 90s. Their numbers leveled off after the turn of the century.

By the time the isolated Yellowstone grizzly population was protected under the Endangered Species Act in 1975, there were as few as 136 bears. The Yellowstone population had been sharply reduced after open-pit garbage dumps that were favorite grizzly feedings grounds were closed in Yellowstone. After they were protected the Yellowstone grizzly population steadily expanded throughout the 1980s and 90s. Their numbers leveled off after the turn of the century.

No one knows for sure how many grizzlies are roaming Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks and the adjacent national forests and wilderness areas and beyond that make up the Demographic Monitoring Area. The best that can be done is to make reasonable estimates.

The estimated total population of grizzlies within the Demographic Monitoring Area is based on a complex model called the Chao2 estimator which extrapolates the overall population from the number of female bears with newborn cubs counted each year.

Van Manen says the Chao2 model underestimates the number of grizzlies, particularly as the population increases. “When we say there are around 700 bears in the ecosystem, that is severely underestimated,” he says. “The bias is as much as 40 to 50 percent.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has been trying for years to declare Yellowstone’s famed bears a conservation victory by removing them from the endangered species list. But that effort has been the source of long-simmering controversy and litigation. The agency delisted the bears in 2007, but environmentalists sued and federal court decisions put the bears back on the endangered list in 2009.

At that time, the court ruled that the Fish and Wildlife Service failed to evaluate the impact of the collapse of whitebark pine forests throughout the Yellowstone region. The pine seeds serve as a major food source for some grizzlies. The agency spent the next few years studying the impact.

In 2013, the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team found no relationship in the decline of whitebark pine and the overall health of grizzly bears, which are famous for being opportunistic omnivores and very flexible in their diet. A second study in 2015 came to similar conclusions.

“We are not seeing for either males or females that the percent of body fat is declining, which would have to happen for these changes in food resources to start taking a toll on the population,” van Manen, one of the authors of each study, says in an interview.

Now, one of the key points of contention is whether the population in and around Yellowstone can be considered recovered in isolation from several other populations in the lower 48 that remain very much a work in progress.

The American Society of Mammalogists and the Society for Conservation Biology sent a joint letter in May 2016 opposing the Fish and Wildlife Service’s then-proposed piecemeal strategy of removing the Yellowstone grizzlies from endangered Species Act protections before the entire grizzly population in the lower 48 states is recovered.

“In our professional judgment,” the letter stated, “both the best available science regarding carnivore recovery and the plain language of the ESA obligate USFWS to manage the metapopulation of grizzlies in the lower 48 states, not just each population individually.”

A metapopulation is a group of populations of the same species that are separated by space. These spatially separated populations interact with individual members moving from one population to another.

“What conservation geneticists have argued for some time is that the focus ought to be on preserving for the long term the whole metapopulation,” says Bergstrom, the Valdosta State professor. “Then, you have to look at how each subpopulation plays into that ultimate goal.”

Van Manen says he isn’t concerned about the loss of genetic diversity if the Yellowstone and Northern Continental bears are prevented from naturally connecting. He says there is no indication now or in the near future of genetic depression with the Yellowstone bears.

He points to a 2015 research paper that concluded the Yellowstone population is “sufficiently large to avoid substantial accumulation of inbreeding depression, reducing concerns regarding genetic factors affecting the viability of the Yellowstone grizzly bears.”

And if genetic depression becomes a factor, van Manen supports the approach of translocating bears. “There would be an easy solution by moving animals from another ecosystem into Yellowstone and make sure they breed and produce offspring. It only takes a few animals in every generation to do that.”

The same research paper states that over many generations the grizzly population “could benefit from increased fitness following the restoration of gene flow particularly given the unpredictability of future climate and habitat changes.”

Conservation groups including Defenders of Wildlife and Greater Yellowstone Coalition stated in a 2015 letter to the U.S. Forest Service concerning grizzly recovery plans that relying on “human assisted trans-location does not support the notion that the [Yellowstone] population has been restored to where it is again a secure self-sustaining member of its ecosystem.”

That supports the conservation researchers’ contention that natural grizzly bear dispersal between the subpopulations helps strengthen the entire metapopulation and would support creation of a healthy regional ecosystem that can support the West’s largest predator and other species such as wolverines.

“So, from the standpoint of greater Yellowstone it is very important that it be allowed to play its role in providing emigrant dispersers to other populations and vise-versa,” Bergstrom says. “Its own health, ultimately in the long term, over many generations, relies on receiving immigrants.”

Connectivity Roadblocks

Grizzly researchers who support natural connectivity versus relying on translocating bears between highly controlled, isolated populations say corridors need to be established between the six grizzly bear recovery zones created by the Fish and Wildlife Service in the 1982 Grizzly Bear Recovery Plan.

So far, none exist. Thirty-five years after adopting the recovery plan, only two of the six ecosystems have a significant number of grizzly bears.

The largest grizzly recovery area is the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, with about 700 bears, in northwest Wyoming, southeast Montana and eastern Idaho and includes Yellowstone and Grand Tetons national parks. The Yellowstone ecosystem includes 34,375 square miles, according to the National Park Service, which notes the “size(s), boundaries, and description of any ecosystem can vary.” The Yellowstone Demographic Monitoring Area rests within the Yellowstone ecosystem.

The largest grizzly recovery area is the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, with about 700 bears, in northwest Wyoming, southeast Montana and eastern Idaho and includes Yellowstone and Grand Tetons national parks. The Yellowstone ecosystem includes 34,375 square miles, according to the National Park Service, which notes the “size(s), boundaries, and description of any ecosystem can vary.” The Yellowstone Demographic Monitoring Area rests within the Yellowstone ecosystem.

The Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem, with about 960 bears, covers 16,477 square miles in northwest Montana and includes four wilderness areas and Glacier National Park.

In addition, there are about 146 grizzly bears scattered among three of the four ecosystems in Idaho and Washington:

- The Selkirk Mountain Ecosystem encompassing 2,200 square miles in northeastern Washington, northern Idaho and southern British Columbia. It has approximately 88 grizzly bears.

- The Cabinet-Yaak Ecosystem encompassing 2,600 square miles in Northern Idaho is believed to have approximately 48 grizzly bears.

- The North Cascades Ecosystem encompassing 9,500 square miles in north central Washington has between five and 10 grizzly bears and is considered the most at-risk population in the lower 48.

- The Bitterroot Ecosystem in central Idaho is one of the largest contiguous blocks of public land in the lower 48 and includes the Frank Church-River of No Return and the Selway-Bitterroots wilderness areas. The 5,600 square mile ecosystem is considered by the Fish and Wildlife Service to be prime habitat for grizzly bears. There are currently no known grizzlies.

The Fish and Wildlife Service’s current policy of recovering grizzly bears by separate populations rather than connecting the existing metapopulation is counter to warnings the agency issued in 2000.

“Wildlife species, like grizzly bear, are most vulnerable when confined to small portions of their historical range and limited to a few small populations,” the agency stated in its failed attempt in 2000 to reintroduce grizzlies to the Bitterroot Ecosystem.

That effort went nowhere because of strong opposition from Idaho, whose former Gov. Dirk Kempthorne famously stated in 2000: “I oppose bringing these massive, flesh-eating carnivores into Idaho.” Kempthorne later served as Secretary of Interior, which oversees the Fish and Wildlife Service, under President George W. Bush.

Grizzly bear advocates now hope that dispersing Yellowstone and Northern Continental Divide grizzlies will eventually end up in the Bitterroot Ecosystem, on their own.

“The biggest available unoccupied habitat that we have for them is the great wilderness areas of Central Idaho,” says Byrd of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition. “The Frank Church, The River of No Return, the Bitterroot Selways — that’s our biggest wilderness area in the lower 48 and they don’t have any bears in them.”

She hopes that over time the bears will migrate there, which will give her group the opportunity “to keep building social tolerance, keep working with the land owners and ranchers and livestock operators to say, ‘We are here to help you with conflicts with bears and wolves.’”

The Fish and Wildlife Service policy, however, is creating obstacles that may be impossible to overcome.

The agency’s policy of removing individual ecosystems from the endangered species list, creating a no death-count zone around the bears’ conservation area and turning over management to the states with game and fish commissions strongly biased against predators, supporting elk and deer populations and emphasizing predator trophy hunting may end dispersal, Mattson and others say.

“Watching them (the Idaho, Montana and Wyoming game and fish commissions) on what they have done with black bears, what they have done with mountains lions, and what they have done with wolves, is that to the extent that they perceive these predators to have negative impacts on harvestable surplus of large herbivores, they will kill these large carnivores,” says Mattson, who is sharply critical of the scientific methods employed by government scientists claiming they are biased to support political agendas.

“And to the extent that these large carnivores are a pest for ranchers and agricultural interests, they will kill predators,” he adds.

Raising the Stakes

To legally justify its decision to remove the Yellowstone grizzly population from Endangered Species Act protections before the rest of the grizzly population is no longer threatened, the Fish and Wildlife Service determined the Yellowstone grizzlies constitute a “Distinct Population Segment” that has reached the carrying capacity of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and therefore should be removed from the endangered species list.

Multiple lawsuits potentially to be filed later this summer are expected to argue, in part, that the use of a Distinct Population Segment was primarily intended to allow the Fish and Wildlife Service to list isolated populations under the Endangered Species Act, not as a mechanism to delist an isolated population like the Yellowstone grizzlies without first assessing the overall impact of removing the Yellowstone population on the remaining bears.

The Washington, D.C. circuit court of appeals issued a decision Aug. 1 that could undercut the government’s Distinct Population Segment approach to removing grizzly bears from the endangered species list. The appeals court vacated the Fish and Wildlife Service’s decision to remove Great Lakes gray wolves from the endangered species list using Distinct Population Segment as a basis for its decision.

The appeals court said the agency does not have the power “to delist an already-protected species by balkanization.” In a unanimous decision, the court ruled the agency “cannot circumvent the Endangered Species Act’s explicit delisting standards by riving an existing listing into a recovered sub-group and a leftover group that becomes an orphan to the law.”

The Fish and Wildlife Service used a similar approach when the agency removed the Yellowstone grizzly population from the endangered species list without considering the impact of that action on the surviving grizzly populations.

“The Endangered Species Act is intended to restore critically imperiled species across their native habitat, not to claim a recovery success story by restoring an isolated subpopulation alone, and effectively turning our National Parks into proverbial zoos,” says Kelly Nokes, carnivore advocate for WildEarth Guardians, a Missoula, Montana conservation group.

The upcoming legal clash between the Fish and Wildlife Service and environmental groups (including the Center for Biological Diversity, which publishes The Revelator) over the legality of removing the Yellowstone grizzlies from the endangered species list comes with high political risk.

Some conservation organizations, including the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, are worried that a successful legal challenge to the Yellowstone grizzly delisting rule may create a serious backlash with possible negative outcomes for the bear.

Byrd, the group’s executive director, says it is unlikely that a new grizzly bear delisting rule written under the Trump administration would be better than the current rule that was primarily developed under the Obama administration.

She also worries that Congress may react by passing laws that would remove all grizzly bears from the endangered species list. And, even more devastating, she says, is the possible gutting of the Endangered Species Act, which is already under unprecedented attack from conservative members of Congress.

“It’s a high-stakes game right now that we all find ourselves immersed in,” says Byrd.

But grizzly experts like Mattson say it is worth the challenge.

“This is about a whole lot more than even just bears on the ground,” he says. “It’s also about our vision of ourselves in the world relative to animals like bears and what is the place in the world for them and how do we consider their recovery in the face of the severe threats that are being propagated everyday by us. Climate change and development, you name it.

“Do we have such an ungenerous and poor vision that we think 500 bears confined to an isolated ecosystem is enough to constitute recovery?

“To my mind, that’s representative of the impoverished spirit.”

* Update: The Greater Yellowstone Coalition has retracted statements made by two of its officials in a taped interview with The Revelator that Grizzly bears, including a female and two cubs, are in the Tobacco Root Mountains. The group is now stating that reports of Grizzly bears in the mountains are a “rumor.” The Revelator has deleted references to Grizzly bears in the region from the story.

A superb informative read !

1. There’s something very wrong with people who want to kill animals for trophies. Nothing more to say about this.

2. We need lots more wilderness, and we need wildlife corridors between wilderness area to prevent inbreeding and for other genetic benefits. Sprawl and all other destruction of natural areas must be stopped and reversed, and animals like bears, wolves, mountain lions, and coyotes should be off limits to hunters.

3. Ranchers are, as usual, a huge problem. Bears and other predators should not be killed or even relocated because they killed cattle or sheep. It’s the cattle and sheep that need to be relocated, or removed altogether.

Curious about your source on a female with cubs in the Tobacco Roots. There are females-with-cubs in the next mountain ranges to the south (Gravelly-Greenhorn), and a lone grizzly showed up in the valley between them this spring, but I haven’t heard of a documented female grizzly in the T. Roots.