A version of this op-ed originally appeared in The Daily Maverick.

In South Africa you can pay a mere $100 to pull the trigger on an aardvark. It’s not a particularly stealthy or aggressive animal; it simply meanders around innocently searching for termites. Yet killing one is somehow considered a sport worthy of applause.

A dead aardvark makes for interesting interior design, and at least six of these animals are now decorative trophies, according to the 2023 professional hunting statistics prepared by the Professional Hunters Association for South Africa’s Department of Forestry, Fisheries, and the Environment and obtained by a wildlife welfare advocate through Promotion of Access to Information Act requests.

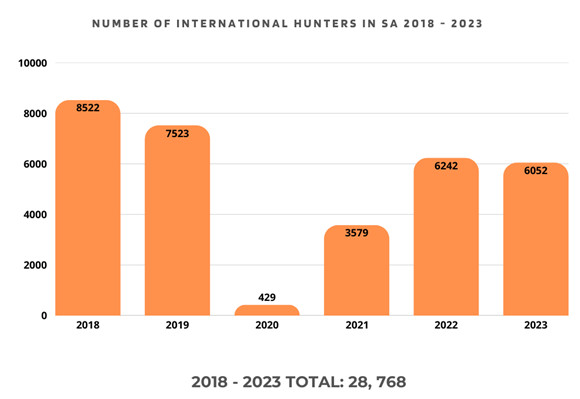

According to this data, 6,052 international visitors to South Africa shot 34,515 animals in 2023, the most recent year for which full statistics are available.

More than half the international visitors — 3,783 hunters — hailed from the United States, while the remainder primarily visited from European countries.

Nearly half the animals trophy hunted (17,111) came from several antelope species, zebras, warthogs, and buffaloes.

But trophy hunters’ choices also included rare and timid animals. Ten meek aardwolves and an equal number of bat-eared foxes fetched $100 each to adorn hunters’ walls — a feat that is neither brave nor athletic.

And since trophy hunting is all about rarity and trophy aesthetics, a total of 722 color variants of springbuck ($1,200-1,700 each) and 459 golden wildebeest ($4,483 each) were killed — species bred specifically for their color and rarity appeal to hunters, and not their conservation value.

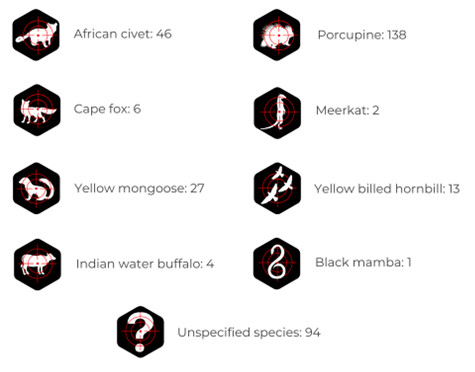

In addition, trophy hunters chose to bag several other puzzling species for entertainment’s sake:

No trophy hunters chose to dart a rhino (an option available for a photo op), but 78 white rhinos were killed for expensive wall art, netting $35,000 each — at a time when poaching rages through the Kruger National Park and KwaZulu-Natal’s provincial parks. Imagine, instead, if someone had invested $2.7 million into improving the functioning of fencing, anti-poaching units, and genuine community upliftment.

No trophy hunters chose to dart a rhino (an option available for a photo op), but 78 white rhinos were killed for expensive wall art, netting $35,000 each — at a time when poaching rages through the Kruger National Park and KwaZulu-Natal’s provincial parks. Imagine, instead, if someone had invested $2.7 million into improving the functioning of fencing, anti-poaching units, and genuine community upliftment.

Hunting of Captive-Bred Lions

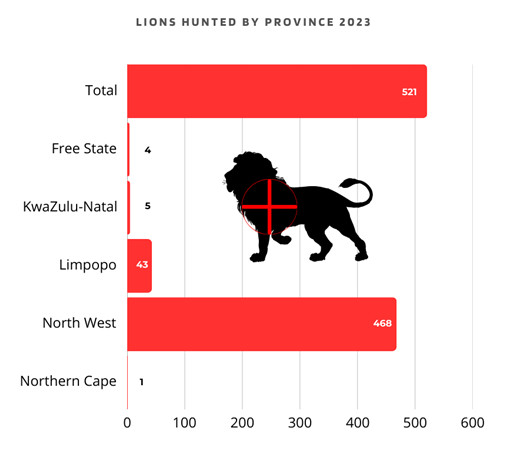

A total of 521 lions were shot for trophies in 2023, and the vast majority (468) of the hunts were conducted in the North West, a province renowned for its captive-bred lion hunts.

Misinformation abounds regarding the legality of captive lion hunts, which have gained euphemisms such as “ranched hunts” to hide the reality that canned or captive hunting is still occurring in some South African provinces, particularly in the North West. Regardless of the terminology used, these hunts utilize captive-bred lions who are released for short period of time (a minimum of 96 hours in the North West) in a small, fenced area for an easy and guaranteed kill.

Misinformation abounds regarding the legality of captive lion hunts, which have gained euphemisms such as “ranched hunts” to hide the reality that canned or captive hunting is still occurring in some South African provinces, particularly in the North West. Regardless of the terminology used, these hunts utilize captive-bred lions who are released for short period of time (a minimum of 96 hours in the North West) in a small, fenced area for an easy and guaranteed kill.

The North West province’s hunting appeal is due to its lack of legislation, which permits hunting outfitters and their clients to kill captive-bred lions and also permits the hunting of exotic predators. No formal permits are required to bag a tiger or other exotic species in the province. A landowner’s written permission is considered sufficient, as Blood Lions researchers confirmed in a 2022 paper.

The Scale of Hunting in South Africa

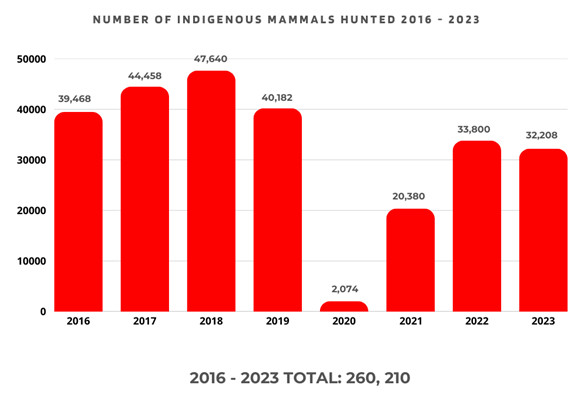

To gain a clearer idea of the sheer scale of indigenous species hunted by international clients, data from 2016 to 2023 demonstrates that 260,210 animals were shot across this eight-year period. The disturbing variety of species includes the smallest cat species, the black footed cat (at five animals) to 562 servals and a staggering 2,968 lions. And that’s with a dramatic decline in 2020 and 2021 during the global pandemic.

Post-COVID-19 hunting figures suggest South Africa has not returned to its hunting glory days. But this does beg the question: Why has the government set lofty hunting targets in the National Biodiversity Economic Strategy? The Endangered Wildlife Trust released a statement questioning whether or not the strategy has determined if a market exists for the extent of the hunting quotas proposed.

Post-COVID-19 hunting figures suggest South Africa has not returned to its hunting glory days. But this does beg the question: Why has the government set lofty hunting targets in the National Biodiversity Economic Strategy? The Endangered Wildlife Trust released a statement questioning whether or not the strategy has determined if a market exists for the extent of the hunting quotas proposed.

Plans to Ramp Up Trophy Hunting

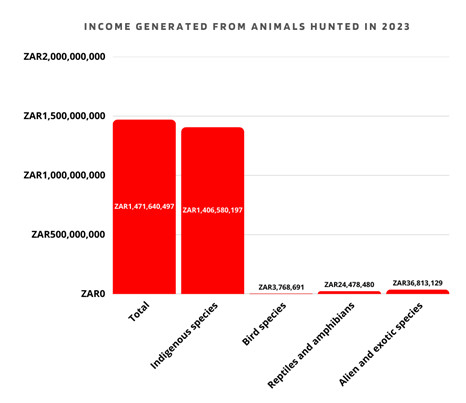

In excess of 1 billion rand (about $53 million) was generated from trophy hunting in 2023, primarily of indigenous species. At first glance this may appear to be significant revenue for South Africa, but game ranching and trophy hunting primarily occurs on private land and benefits a small number of wealthy landowners who are very often surrounded by communities living in poverty.

South Africa’s wildlife legislation is geared for economic development at the cost of considering more progressive ways of approaching the conservation of biodiversity and addressing the core issues affecting poaching and biodiversity loss. While the National Biodiversity Economy Strategy, gazetted for public comment in March 2024, is to be lauded for its intentions to protect biodiversity and improve economic benefits for those living in poverty, a closer examination raises concerns that it risks exploiting the natural environment to the benefit of only a privileged few.

South Africa’s wildlife legislation is geared for economic development at the cost of considering more progressive ways of approaching the conservation of biodiversity and addressing the core issues affecting poaching and biodiversity loss. While the National Biodiversity Economy Strategy, gazetted for public comment in March 2024, is to be lauded for its intentions to protect biodiversity and improve economic benefits for those living in poverty, a closer examination raises concerns that it risks exploiting the natural environment to the benefit of only a privileged few.

The strategy further touts the idea that “consumptive use of game from extensive wildlife systems at scale that drive transformation and expanded sustainable conservation compatible land-use” will “increase the GDP contribution (through) consumptive use of game from extensive wildlife systems from R4.6-billion (2020) to R27.6-billion by 2036.” That’s nearly $1.5 billion.

How this will occur remains unclear, as this would only be achievable if such economic growth brings more than 16,500 hunters to South Africa to shoot almost 100,000 animals each year by 2036. To put this goal in perspective, hunters would need to kill more than 10,000 lions, 1,300 elephants, 3,000 white rhino and 30,000 buffalo from 2022 to 2036 to achieve these targets. This would require industrial-scale production of wildlife that is neither ecologically sustainable nor in line with emerging recognition of animal wellbeing.

How this will occur remains unclear, as this would only be achievable if such economic growth brings more than 16,500 hunters to South Africa to shoot almost 100,000 animals each year by 2036. To put this goal in perspective, hunters would need to kill more than 10,000 lions, 1,300 elephants, 3,000 white rhino and 30,000 buffalo from 2022 to 2036 to achieve these targets. This would require industrial-scale production of wildlife that is neither ecologically sustainable nor in line with emerging recognition of animal wellbeing.

Fierce Opposition to Animal Wellbeing

The captive predator industry is fighting tooth and nail to ensure their exploits continue, despite Dr. Dion George’s stated intentions to close the industry and all its associated activities with lions. The further inclusion of an “animal wellbeing” clause in the amended National Environmental Management Laws Amendment Act has created enormous backlash from the SA Hunters and Game Conservation Association, who have now taken DFFE to court to have this removed.

Wellbeing is defined in the legislation as “the holistic circumstances and conditions of an animal, which are conducive to its physical, physiological and mental health and quality of life, including the ability to cope with its environment.” Considering an animal’s wellbeing has many hunters bristling at the very notion.

As trophy hunting faces increasing international opprobrium, ethical tourism increases in importance and both numbers of animals hunted and international visitors decline, the continued focus of South Africa in supporting trophy hunting remains highly questionable.

Previously in The Revelator:

Trophy Hunting Propaganda Is One More Form of Greenwashing