[Editor’s note: This article is a joint publication of SEJournal and The Revelator.]

This past May, as the world started to emerge from the restraints of the COVID-19 epidemic, a paper in the journal Nature warned that future pandemics were coming, due to climate change, chemical pollution, invasive species and other factors.

The most likely cause of future outbreaks, the researchers found, could come from a threat we don’t talk about enough: biodiversity loss.

The threat of emerging pandemics will be even greater, according to the paper, when these factors combine. “For example,” the authors wrote, “climate change and chemical pollution can cause habitat loss and change, which in turn can cause biodiversity loss and facilitate species introductions.”

It’s a warning that science writer David Quammen, author of the award-winning 2012 book Spillover, has been sounding for years.

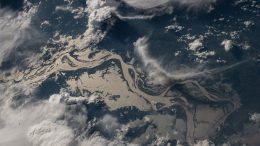

As he said on a panel at the 2023 Society of Environmental Journalists conference in Boise, Idaho, the threats of extinction, climate change and emerging diseases are “three big, brown, churning, murky rivers of woe, with some channels interconnecting now, but flowing parallel, independently to a great degree, but coming from the same source, … the human footprint.”

Connecting the Dots

Quammen has been writing about the extinction crisis since 1981, initially as a columnist for Outside magazine.

Since then his work for National Geographic and other publications, as well as his many books, has taken him all over the world. He’s written about emerging diseases, including HIV and COVID-19, as well as climate change and other threats.

Since then his work for National Geographic and other publications, as well as his many books, has taken him all over the world. He’s written about emerging diseases, including HIV and COVID-19, as well as climate change and other threats.

And he encourages other journalists and people working in environmental fields to do a better job connecting the dots.

“When many journalists and activists talk about climate change, they tend to think that this is the big, all-encompassing problem and everything else is a subcategory,” he told me by Zoom from his book-lined home office in Bozeman, Montana.

“It’s important for people to understand: We do not have one huge problem called climate change, in which all other problems are subsets. We have three coequal problems that need to be understood fully in their severity and in their independence as well as their interconnectedness. Those are climate change, loss of biological diversity, and emerging pandemic threats.”

For journalists, as well as the public, that means we need to look a little deeper.

“Climate change is a problem that comes to us, right? It comes home to us. It comes to everybody,” Quammen said. “Loss of biological diversity can be happening at a distance.”

That might make the changes hard to see, especially if your vantage point doesn’t change much.

“If you go out and about, if you’re a traveling journalist as I’ve been, then you have seen with heartbreaking concreteness the loss of biological diversity over the decades. For instance, the decline in insect populations around the world, the decline in migrating songbird populations, the decline in populations of a lot of other creatures that perhaps need a particular high altitude or cold habitat, ranging from bumblebees to polar bears.”

Seeing these species, seeing these places, offers journalists an opportunity to illustrate to readers how these major environmental issues connect and to bring them to life — and hopefully help readers feel connected to them in return.

“Connectivity is just one of the very great truths,” Quammen said. “It’s the essence of ecology and the essence of human history, which I think of as a subcategory of ecology rather than the other way around.”

Making It Real

Illustrating that connectivity is especially important when we’re writing about far-flung wildlife that people won’t encounter in Bozeman or Boise or New York City.

“Most people were never going to see a pangolin, polar bear or lowland gorilla except maybe in a zoo. My particular career and route through life have given me the opportunity to see those creatures and a lot of others in the wild. And I’ve felt that it was part of my duty, as well as my opportunity, to try and make those creatures real, at least at one remove, in the minds and the hearts of readers who will never have the same opportunity.”

That could help, for example, to provide some emotional understanding of the wildlife trade threatening all eight species of pangolin (a trade that’s been linked to the COVID-19 pandemic), or the loss of sea ice threatening polar bears.

“My job and my opportunity are to go out there as a proxy for other people,” Quammen said.

“I get to say, ‘Hey guys and gals, this is happening. Look at this creature through my eyes. This is a magnificent, appealing, complex, amazing creature. And yet look at this situation that this creature is in. It’s outrageous, it’s heartbreaking, it’s dangerous, but it’s reversible.’”

‘Golden Thread of Hope’

Despite the dangers he’s chronicled, Quammen brings a lot of humor to his work.

“I am one of those people who believes that almost nothing is too sacred for a joke to somehow enrich the contemplation of it,” he told me. “I really believe that when you write a rich piece of nonfiction, a piece of journalism about the environment, about the living world, if you can make your audience laugh and cry and think and maybe see the world in a slightly different way, that’s the goal. Because those moments are best when they come unexpectedly, and they knock the reader a little bit off balance.”

He also brings another H- word to his work, as he discussed in a recent interview with Orion, where he said hope is a duty when writing about the extinction crisis.

Sure, there’s a lot of gloom in the extinction crisis, but Quammen told me we should always be looking for solutions, or at least small bits of progress.

“I think we should all do that,” he said. “I do that in my most recent book, The Heartbeat of the Wild, where I write about some situations, some efforts, some conservation models around the world that are working pretty well, and therefore they give me hope.”

That hope, he admitted, “is sandwiched between a lot of concern and doom and pessimism.”

And, he cautioned, writing about it “should never be programmatic.”

Too many gloomy articles contain “a hopeful ski jump at the end,” Quammen said. “It’s autopilot, it’s predictable. There are other ways to lace a golden thread of hope through the narrative tapestry that you’re creating. And I think it’s important to do that.”

Previously in The Revelator:

Anthrax in Zimbabwe: Caused by Oppression, Worsened by Climate Change