When I read news about the latest IPCC climate assessment report, or predictions of imminent mass extinction, I admit that the statistics — the exact degree of warming, the number of feet sea levels will rise, how many species will die — find fewer footholds in my brain than the overwhelming sorrow they elicit.

To paraphrase Maya Angelou, I don’t always remember the numbers, but I remember how they make me feel.

It’s hard to focus on the individual words when your eyes are blurry with tears.

It’s love that makes me run my hands along tree bark ridges. It’s love that moves me to feed the birds that grace our house in winter. And it’s grief — love’s counterpoint — that makes me care so passionately about what threatens the neighbors I love.

That somatic experience informs why I believe climate activism is most effective when it taps into the climate grief, instead of repeating statistics that too often overwhelm people into numbness.

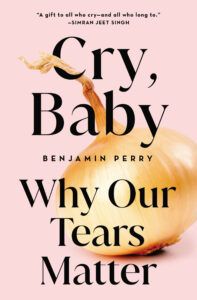

I wrote a book called Cry, Baby: Why Our Tears Matter that will be published this May, and I think the science of crying has important lessons to teach organizers about how to motivate people. That may sound counterintuitive: Crying is a deeply personal act and climate action is, fundamentally, about mobilizing collective action. But that framing obscures both the social dimensions of weeping and the ways in which personal psychology is at the core of large-scale change.

I wrote a book called Cry, Baby: Why Our Tears Matter that will be published this May, and I think the science of crying has important lessons to teach organizers about how to motivate people. That may sound counterintuitive: Crying is a deeply personal act and climate action is, fundamentally, about mobilizing collective action. But that framing obscures both the social dimensions of weeping and the ways in which personal psychology is at the core of large-scale change.

There’s some disagreement among psychologists about why we cry emotional tears. In 1985 William H. Frey published the much-heralded Crying: The Mystery of Tears, in which he found emotional tears contain higher concentrations of certain neurotransmitters than tears caused by chopping onions. He hypothesized that the reason we evolved the ability to cry from deep feeling — and why we often feel better afterward — is that our tear ducts help release chemicals from the brain. More recently researchers like Ad Vingerhoets have cast doubt on this theory, instead suggesting that tears primarily serve a social function. The jury is still out about Frey’s work, but evidence that tears facilitate interpersonal bonds is undeniable.

One recent experiment found that in 41 countries across six continents, in every country, seeing someone cry made people more likely to offer help. Qualitative studies also affirm this link: In a paper analyzing 89 “crying events” at a Hong Kong shelter for abused domestic workers, Hans Ladegaard found that tears helped participants talk about their trauma, and increased the emotional support provided by other members. In my own research, people I interviewed regularly described times when a stranger offered them assistance or comfort after seeing them cry.

There’s something about seeing palpable evidence of other people’s grief that sparks a response.

So what light does this shed for climate activism? One takeaway is how important it is for people to see the climate grief their neighbors carry. It can seem, as we move about our lives, that other people do not share the overwhelming sorrow and anguish we feel when thinking about our ecological future. Certainly we’re not all equally concerned, but more pain lurks beneath the surface — particularly for young people — than we see or name. Providing avenues to discuss this hurt can help move people through their emotions toward action.

This underscores the importance of storytelling: Narratives about climate activists transforming pain into resistance against the forces that are killing us help people see how they can do the same.

One counterintuitive lesson I learned from my crying interviews, however, is that often people don’t cry when they’re most overwhelmed. It seems, broadly speaking, that loss increases weeping to a point, but once pain becomes too intense and a threshold is crossed, people report crying less and retreating into numbness.

I fear this dynamic is very much at play in our climate crisis. The scale of death projected in scientists’ reports is so staggering that it can be paralyzing. To contemplate, for example, projections that one-third of the planet’s species could go extinct by 2050 can provoke an immobilizing anguish. To consider there may 1.2 billion climate refugees in that same time span is a disaster so enormous that any action we take can feel insignificant. But this is, of course, a lie. What we do matters.

Claiming that truth requires not just acknowledging suffering but affirming our collective power to change how much we suffer. This isn’t just an intellectual exercise, it’s emotional work.

But here’s the last truth I’ll share about crying: When we cry, we deepen our relationship to the object of our grief. And, right now, that’s essential. The forces of extractivism deliberately inculcate and depend on our isolation and despair. They want us to feel alone in our anxiety, separated from community that can do something about it.

As Indigenous writer Kaitlin Curtice shared in an interview for Cry, Baby, “As we get older, we start learning lessons of colonization — the land is not someone you interact with, the land is a commodity. We lose the emotional connection we had to the Earth as a being, as our mother, as a friend.” For example, we are trained to think about climate refugees as problems, not as people who deserve an abundant future.

Moving through grief is an opportunity to reforge these bonds, to feel them in our body and honor the claim they make upon our life.

![]()

Previously in The Revelator:

Why Every City Needs a Climate Storyteller