When it comes to climate change, nature hasn’t had the luxury of waiting for foot-dragging politicians or stonewalling corporations or science deniers. Countless species are already on the move.

“Just as the planet is changing faster than anyone expected, so too are the plants and animals that call it home,” writes biologist Thor Hanson in a new book that explores the field of climate change biology.

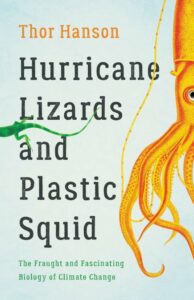

In Hurricane Lizards and Plastic Squid: The Fraught and Fascinating Biology of Climate Change, Hanson talks to scientists all over the world about how plants and animals are moving and changing, and why some are inherently better set up for success than others. Hanson also discusses evolution-in-action, what happens when hundreds of thousands of species hit the road at once, and what we can learn from scientists with a front-row view of the climate crisis.

Hanson’s own understanding of the climate crisis comes from decades of fieldwork where climate issues rose to the top, even when it wasn’t the intended area of investigation. “You’d go to the field expecting to study one thing and come home with a very different dataset because the conditions on the ground had changed so much,” he told The Revelator.

What have you learned about which species are most vulnerable to climate change and those that are better capable of adapting?

If you start to look for overarching themes in the field of climate change biology, one that comes out quickly is the difference between specialists and generalists in nature. And by that I mean the creatures or plants that are very flexible and general in how they can behave and adapt. Those are the ones that are particularly good at thriving under a variety of conditions. And there are many examples of this that we’re so familiar with, like dandelions, which can bloom any time of year. They can grow in the gravel of your driveway and be small and tiny. Or they can grow in the lush area of the lawn that you water and be gigantic. They’re just extremely flexible generalists.

So animals or plants that are in that category are already well-suited to cope with change.

The ones that stand out as the most vulnerable oftentimes are the specialists that depend upon a particular type of habitat or relationship. For example, the very tightly co-evolved relationships between pollinators and the flowers they pollinate. Sometimes it’s one pollinator specializing on one particular flower. Those kinds of tight relationships are very much at risk from this kind of rapid environmental change.

Is it possible to quantify how many species are moving in response to climate change and how that’s changing ecosystems?

I spoke with a number of people about this, but one in particular, a scientist named Greta Pecl, said that we know that between 25% to 85% of species on the planet are moving already in response to climate change. But when it comes to what that means and how those novel ecosystems with all these new neighbors will get along in the future, she said “we haven’t really got our shit together on that.”

It’s extremely complicated to try to predict how these ecosystems will settle through this period of change. Animals, plants, pests, pathogens — all of these things are moving and recombining in habitats in ways that they never have before.

Are you surprised by how fast some of the change is happening?

Yes, the speed of the responses for some things has been almost instantaneous. One of the great examples of that would be the Humboldt squid in the Gulf of California. When the waters warmed, fishers and everyone there thought that the squid had moved on. It’s a mobile species and things had gotten too hot and they disappeared.

But when folks went out and did surveys, they found in fact that the squid were still there and more plentiful than ever. But the warm water or the stress from that heat had triggered a complete lifestyle change where they were maturing twice as fast, reaching only half their normal size and eating different foods.

Their adult bodies were so much smaller and so different that they were too small to bite the hooks that people had been using for decades to catch these big squid. The few that they could hook, they assumed must be juveniles or maybe even another species, and they were throwing them back.

So that is an example of the inherent flexibility built into a species. We all have a bit of what they call in biology, plasticity. It’s built into your genome to be able to deal with a certain amount of environmental change. Some species, like this squid, have a lot of it. Some species have very little. So it’s the ones that lack plasticity that are more at risk.

That’s an example of what we see a lot in nature right now is these plastic responses that are already built into species’ genomes. But there are now a few examples of evolution taking place in response to climate change and taking place quickly.

One of these stories comes to us from a scientist named Colin Donihue, who did some work on a little anole lizard that lives in the Turks and Caicos islands in the Caribbean. Colin and his team were there surveying and taking all these measurements of the lizard because there was going to be a project to remove non-native rats that were eating the lizards. And they wanted to see the response to getting rid of those rats.

But two weeks after their field season, two category four hurricanes slammed across the island with extreme winds, uprooting trees and destroying structures and causing flooding. That took the rat eradication project off the books, but Colin and his team realized it was a rare opportunity to look at what impact the hurricane had on those lizards.

So they went back down there, repeated the same field measurements and learned that the surviving lizards had measurably larger toe pads and stronger front legs for gripping tight to the branches and tree trunks they were holding onto during those high winds. And the odd part was that their back legs were smaller.

To figure out why they simulated hurricane-force winds with a leaf blower and watched the behavior of the lizards. They learned that, in fact, they hold on tightly with those strong front legs and their back legs and tail flap out like a sail in the wind. So if you have smaller back legs, it’s less drag and you have a better chance of hanging on through the hurricane.

They documented all of this and then went back again later and showed that indeed these traits were being passed on to the next generation. And then they looked at a broad sweep of anoles across the Caribbean and found that this sort of selection — this evolution — has been going on in response to hurricanes all over the place. Wherever you have frequent, strong hurricanes, the anoles in those populations have these larger toe pads and stronger front legs.

So you can really see the effects of extreme weather playing out just over the course of a few generations.

Are you ever worried that when people read about the ways that some species are adapting it may make them think that climate change won’t be a problem for most plants and animals?

Yes, it’s a concern, I think, of anyone working in this field. They want to document what’s going on, but not give people the sense that everything’s going to be fine. In fact, it’s not going to be fine. There’s still a great cause for worry. This is still a crisis.

It’s always important in a discussion of climate change biology to call out that we have some very compelling and even inspiring examples of rapid change and response and survival. But those are counterbalanced by the many species that can’t respond quickly — that don’t have that flexibility — and that are at risk of perishing.

But what the study of climate change biology allows us to do is not to cease worrying, but rather to worry smart. It puts us in a much stronger position in terms of how we allocate scarce resources to these problems. If you understand the species and the systems that are most vulnerable, if you understand the ones that have some natural resilience, you’re in a much better position to manage the crisis.

And another thing that can be in short supply is emotional capital. I think it’s very easy to feel despair, to feel overwhelmed by such a large problem. So worrying smart also allows us to allocate our emotional capital, too.

On that note, did you come away from this research feeling more worried or hopeful?

When you think about all these scientists who’ve spent their whole careers studying species or ecosystems that might be really suffering, you’d think that they would have more reason to worry and lose hope than anyone.

Yet what I encountered, without fail, was people who remained passionate and committed to their research efforts really felt like what they were doing was making a difference. And I came away from that surprised and somewhat gratified by the power of curiosity as a response to this crisis. It’s a balance to the negative feelings.

I mean, despair, if you will, just leads to more despair. But curiosity leads to learning. And it leads to action. I really saw that across the board with the scientists that I spoke with. And I took that as a message of inspiration.

![]()