One of the first Superfund sites in the United States remains one of the most polluted.

From the late 1800s through the 1960s, miners extracted lead and zinc from the ground beneath the Tar Creek area in northeastern Oklahoma. But 50 years after the mine was shuttered, the region’s toxic legacy still seeps from boreholes into the water and drifts in the wind from tailings piles. Even now, the unstable ground threatens to swallow up homes.

Neighboring residents — including those of the Quapaw Nation and Ottawa County’s other eight tribes — have paid a heavy toll. The mounting environmental and human health threats led the federal government to declare 40 square miles of the area a Superfund site in 1984.

Despite efforts by the Environmental Protection Agency and state and tribal governments, problems persist. One area of grave concern is the region’s watershed. Tar Creek, which flows through the towns of Commerce and Miami, runs orange with acid mine drainage. The contamination travels downstream to Grand Lake O’ the Cherokees, a major source of drinking water and recreation.

This year Tar Creek made the list of the 10 most endangered rivers in the country, an annual call-out from the nonprofit American Rivers.

The designation came as no shock to Rebecca Jim, who worked for 25 years as a counselor in the local school district and heads the nonprofit LEAD Agency (Local Environmental Action Demanded). LEAD Agency has been raising awareness about the environmental and health problems from the Tar Creek Superfund site.

The Revelator spoke with Jim about what decades of pollution have meant for area residents, why cleanup efforts have fallen short, and what else needs to be done.

What happened at Tar Creek to cause a toxic waste site worthy of Superfund designation?

They mined down in some places over 300 feet deep. And they weren’t open-pit mines. They were random pillar mines. The pillars were left underground to protect the miners, but when the mines began to play out some of those pillars were mined and no record was kept of which ones.

That led to a series of collapses that occurred and continue to occur. Oklahoma Senator [Jim] Inhofe finally agreed to a study on the risk of subsidence under the towns of Picher and Cardin. The results [which led to a buyout for residents] showed that the people in those towns were at great risk — a cave-in could have been imminent. It still could.

Another problem is the water. Our water body, Tar Creek, is mine-water discharge — a million gallons have been flowing from the site every day for 42 years now. And all of that flows down our creek into the Neosho River. There are also two more Superfund sites in Kansas and Missouri with waste that flows down the Spring River. The Neosho River and the Spring River meet and form the Grand River, which is dammed. So it collects all those metals in Grand Lake, which is also a drinking-water reservoir and a fishing paradise.

What’s been done?

We were one of the very first Superfund sites in the nation and EPA came in with great ambitions, perhaps, to do something. They did something, but they didn’t do enough and what they did do didn’t work. They tried to put up a berm to keep the acid-mine water from entering Tar Creek, but the berm didn’t hold.

In that early work they did fill some mine shafts and some boreholes to try to keep water from entering the aquifer and filling back up. But then, bless her heart, [Love Canal activist] Lois Gibbs did what we didn’t do: She went on TV and made all these posters saying, “Love Canal really needs some help.”

When she did that, the media left us and then EPA did, too. We were an abandoned mine site and then we were abandoned by EPA.

How has that affected the community?

We probably still would be abandoned if it hadn’t been for the Indian Health Service discovering that our children were lead poisoned.

In the 1990s Don Ackerman [a researcher at the Indian Clinic] looked through [the Service’s medical records] and saw that 34% of our kids were lead poisoned and so EPA had to come in and respond. They found that it was true that the children were being lead poisoned, but in some of the towns it was even worse than Don’s findings.

I worked for 25 years as an Indian counselor in Miami, Oklahoma beginning the year before Tar Creek turned orange — 1978. I had worked with kids in other school districts before I came here, and our kids were different. They couldn’t sit still, couldn’t concentrate. They struggled, they failed, they cried, they felt bad about themselves and they would either act out or drop out. With a third of our kids lead poisoned, that’s a lot of children in every classroom with issues to work through.

But Don’s study led to action.

What EPA began to do was to remove contaminated soil. That started in 1995 and they’re still doing it. Initially it was in “the box,” which is what they call the line that designates the boundary of the Superfund site. But we didn’t think that was adequate. Now it’s the whole county. Any resident in Ottawa County can have a yard tested for lead and if it’s found to be high, EPA will fund replacing it.

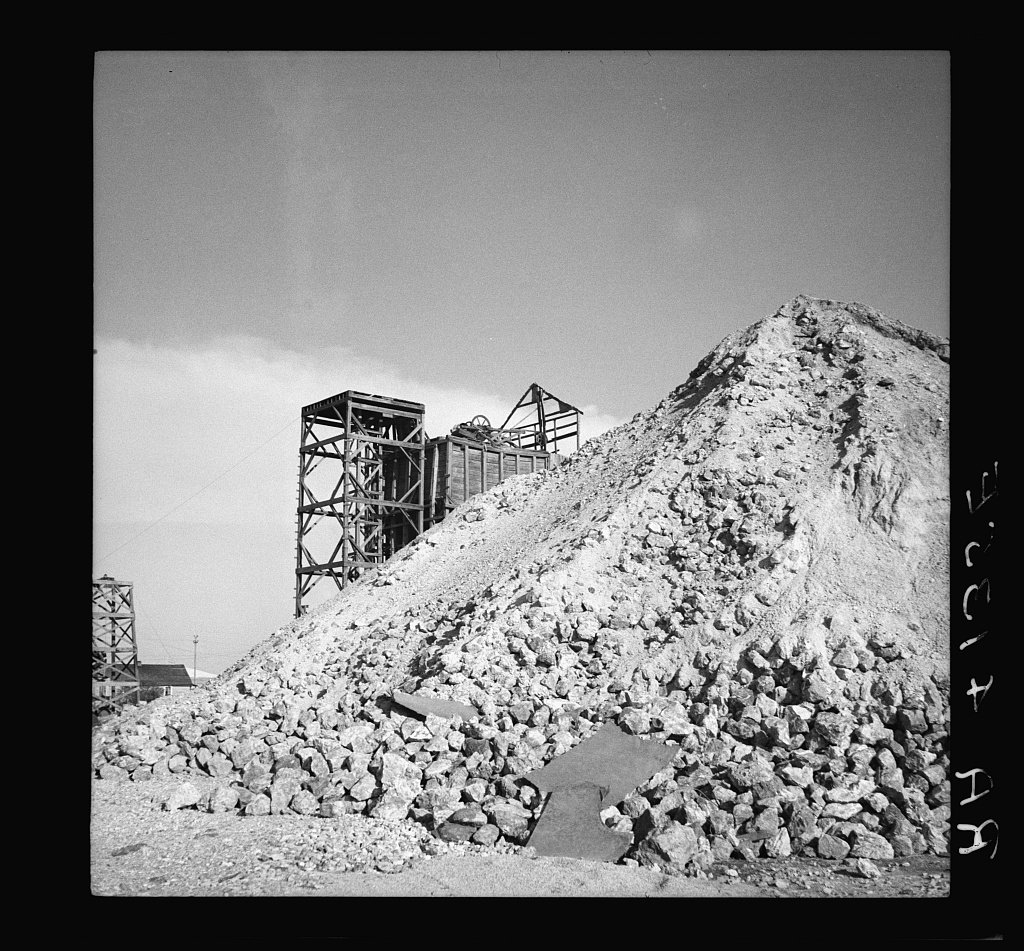

At the same time they’re hauling away mine waste called “chat piles,” which are really like mountains of toxic tailings [200 feet high]. These are loaded with lead, cadmium, arsenic, zinc and manganese. And these are still blowing in the wind.

We know that it’s not just lead, it’s not just one metal, but it’s the cocktail of metals that hurt us. They’re all dangerous. I’ve seen some of my former students dying from kidney failure at young ages. That’s probably from the exposures they’ve had all through their lifetimes.

EPA has given the Quapaw Nation a contract for the cleanup work, but they’re not funded enough to do much at a time. It looks like a big operation, but at the rate they’re going it will be decades before they’re done.

What’s the current state of the creek?

Nobody’s doing anything about that water. It’s running unchecked. There’s always mine-water discharge coming down. It comes up from the aquifer through old boreholes, air vents and other cracks in the surface. It used to be one area, but now the whole property is bleeding. It’s just pouring into Tar Creek. Nobody’s tried anywhere at all to stop that discharge.

I believe that if enough water was pulled out to lower the aquifer, we could get ahead of it and if we could keep pulling out enough water, we could add a wastewater-treatment system. That was in the original plan, but they rejected it because it cost too much money. It would have been safer than having that water discharge all these years and end up in a drinking-water reservoir, lowering the IQ of anybody that eats that fish or eats any plants that grow along the creek, any wild onion you dig up or any blackberry you pick. Anything along the creek bed should not be consumed.

When EPA first came in, we were all excited: “We’re going to get this fixed.” We all believed that they would do something, they would do it quickly, it would be resolved and we’d have fish in that creek again. And people could play in it again. But then they walked away and they did nothing and have still done nothing for that creek. Now you have 40 years of children not being able to play in it. Pretty soon there’s no memory of the joy. It’s forgotten.

What do you want to see happen now?

I’m hopeful of this new infrastructure bill that’s been introduced, which would put a tax back on polluters. We want Superfund funded. It ran out because Congress wanted proof it was doing something and so they set aside mega-sites like ours so that they could clean up the ones that were the size of a filling station. They did those first, so they could get their numbers up.

And a lot of sites got cleaned up. But not ours.

Another problem is that Senator Inhofe put in an amendment in the National Defense Authorization Act that will lead to Grand Lake being two feet deeper. But that means when it rains heavily, Tar Creek and the Neosho River will back up quicker and deeper, leading to more flooding and contamination of areas that have already been cleaned up or yards that have never had any exposure before.

We also hope the designation [from American Rivers] is a wake-up call. We’ve got a diagnosis here where we are in danger — somebody has noticed. I think it will be a rallying cry for our community to say that we want it to be better.

This is our moment of reckoning. Now is our turn, we’re going to love this creek again.

![]()