BLUFF, Utah— The first national monument approved by President Theodore Roosevelt after the passage of the 1906 Antiquities Act was Wyoming’s Devils Tower — made famous to a generation of 1970s moviegoers by Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Roosevelt’s proclamation said that the isolated, dramatic rock outcropping, whose sweeping vertical lines jut 867 feet out of the ground, is “an extraordinary example of the effect of erosion as to be a natural wonder and object of historic and great scientific interest.”

Devils Tower set the stage for Roosevelt to create Grand Canyon National Monument in 1908, when he set aside 818,000 acres for protection and signaled that large-scale national monuments were part of the president’s prerogative.

But as important as the Grand Canyon is to the nation’s environmental and cultural heritage, historical records reveal that the primary reason the Antiquities Act was passed was to preserve ancient culture — to stop the widespread looting of American Indian ruins scattered across the Four Corners region of the Southwest.

For more than 20 years before the passage of the Antiquities Act, a debate had raged in academia and on Capitol Hill on how to stop the pillage of archeological treasures. Newly arrived settlers were looting ruins, ceremonial structures and burial grounds scattered across vast canyons, mesas and washes — including the land that’s now part of the new, and under President Trump hotly contested, Bears Ears National Monument.

It took 110 more years than Devils Tower to put the 1.35-million-acre Bears Ears monument in place, but it finally happened this past December with President Obama’s signature. But this week Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke confirmed that the Trump administration will follow through on its long-threatened plans to shrink the monument — a move that brought instant condemnation from the coalition of five southwestern tribes that first proposed Bears Ears for protection.

“Any attempt to eliminate or reduce the boundaries of this Monument would be wrong on every count,” the Bears Ears Inter-tribal Coalition said in a statement. “Such action would be illegal, beyond the reach of presidential authority.”

Largely lost in the debate over Bears Ears and other sites is this: The monument in southeast Utah was the first-ever driven by tribal interests wanting to see this place protected for its deep cultural and ecological significance. And attempts to roll it back are provoking bitter reactions among tribal leaders who worked most of this decade to research and document the significance of Bears Ears.

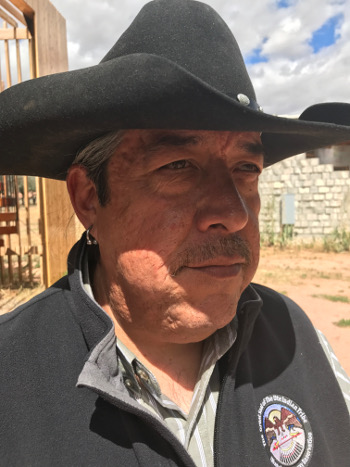

“It’s an attack — an attack on tribal nations,” says James Adaki, Navajo Nation Oljato Chapter president and a Bears Ears commissioner.

Obama’s proclamation created the Bears Ears Commission, which includes representatives from the five southwest tribes that proposed the monument. Established this past March, the commission will work now collaboratively with the U.S. Forest Service and the Department of the Interior to develop a management plan.

Adaki and other members of the Bears Ears Commission interviewed by The Revelator during a recent joint management meeting with federal officials in Bluff, Utah, said that opposition to the monument and Trump’s review of Bears Ears in particular is rooted in distrust, lack of knowledge, disrespect of tribal governments and, in some instances, racism.

Despite the monument’s uncertain future, federal officials and the commission engaged in daylong discussion on May 16 on developing a management plan. Even as they moved forward, federal officials said no money would be spent to purchase and install Bears Ears National Monument signs until the completion of Trump’s review process.

The good-faith discussions during the management meeting don’t defuse the strained relationship between the tribes and monument opponents which became further inflamed by a statement last month by Utah Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch, who said the tribes were “manipulated” into supporting Bears Ears National Monument.

“The Indians,” Hatch said, “they don’t fully understand that a lot of the things they currently take for granted on those lands, they won’t be able to do it if it’s made clearly into a monument or a wilderness. Once you put a monument there, you do restrict a lot of things that could be done, and that includes use of the land…Just take my word for it.”

Adaki says Hatch’s comments were “an insult against tribes, because we know what we are doing.”

Davis Filfred, the Navajo Nation’s spokesman for the seven Utah chapters and a Bears Ears commissioner, says the monument opponents want the designation rescinded so they can exploit natural resources.

“They want to go after coal. They want to go after petroleum, uranium, potash. They want to clear all the timber,” he told me, during a break in a commission meeting held in Bluff at a Utah State University auxiliary building beneath sweeping cottonwood trees.

Filfred, a former Navajo law-enforcement officer, is particularly concerned about protecting the extraordinary biodiversity at Bears Ears.

“This is habitat for a lot of species. We have big trophy elk, trophy mule dear, antelope, bobcat, mountain lions, bears you name it. Not only that, we have vegetation. They just want to clear that and make it a parking lot and just terrorize it,” he says.

“And we’re saying no,” he says emphatically. “That’s sacred ground.”

Just beneath the heated debate over Bears Ears, Filfred says, lies the unmistakable odor of racism against Native Americans, which, he says is “absolutely” a force driving the opposition.

“That’s what it is, plain and simple,” he says. “It’s very obvious.”

Bears Ears: A History of Exploitation

People have been profiting off Bears Ears and similar sites for more than 150 years. Starting in the mid-to-late 1800s, artifact hunters routinely plundered burial grounds and tore down walls of irreplaceable stone-and-masonry structures in search of treasures buried beneath the Ancestral Puebloan ruins across the Southwest.

Pottery, baskets, human remains, tools, weapons and other artifacts disappeared into the private market. Major museums, including the American Museum of Natural History in New York, sponsored expeditions to excavate ruins and extract tens of thousands of artifacts for their collections. Southwestern tribes, many of whom had cultural and historical ties to the ancient sites, lacked any substantial influence to stop the exploitation.

Hoping to reverse this trend, renowned archeologist and anthropologist Edgar L. Hewett identified the Bears Ears region, which he then called the Bluff district, in 1904 as one of the top four areas in the Southwest in need of immediate protection.

“No scientific man is true to the ideals of science who does not protest against this outrageous traffic, and it will be a lasting reproach upon our Government if it does not use its power to restrain it,” Hewett wrote in a Sept. 3, 1904 memorandum on preserving the “historic and prehistoric” ruins of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Utah.

Hewett, believed by historians to have closely worked with Progressive Era leaders in President Theodore Roosevelt’s Interior Department, also wrote the language for the Antiquities Act, which passed the House and the Senate without a single word changed. Roosevelt signed it into law on June 8, 1906.

“There seems little doubt the impetus for the law that would eventually become the Antiquities Act was the desire to protect aboriginal objects and artifacts,” wrote legal scholar Mark Squillace in his 2003 treatise, The Monumental Legacy of the Antiquities Act of 1906.

The destruction of antiquities on Bears Ears has continued unabated for the past century. Local San Juan County residents have a long history of pilfering the ruins, which has led to high-profile federal police raids in Blanding that increased bitterness between the mostly white Mormon community and nearby tribes.

“In southeastern Utah, there are generations of families who have looted cultural sites and removed precious archeological resources from public land,” according to the Bureau of Land Management’s Office of Law Enforcement and Security report included in an October 2016 San Juan County-commissioned legal analysis arguing against designating Bears Ears a national monument.

“For many of these individuals, these activities were part of a typical weekend outing,” the report reads.

A Long-delayed Designation

Starting in 1906 the Antiquities Act gave presidents sweeping authority and the sole authorization to create national monuments — without prior congressional approval or the need for consultation with local communities.

The law states, in part, that the president “could declare by public proclamation, historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other areas of historic and scientific interest, that are situated upon lands owned and controlled by the Government of the United States to be national monuments.”

The law placed no restrictions on the size of monuments, a major difference from previous bills that had been introduced in the years leading up to passage of the Antiquities Act that limited monuments to about 640 acres.

President Jimmy Carter set aside 56 million acres for various national monuments in Alaska in December 1978, the most for a land-based national monument at one time. Like Obama, Carter was severely criticized by Republican leaders for an allegedly dictatorial action they saw as an infringement of their rights. But Carter’s designation was never overturned.

President Roosevelt swiftly made use of the Antiquities Act power, and the first two areas on Hewett’s most endangered ancient cultural sites list soon found themselves protected. The third was protected in 1916 by President Woodrow Wilson.

Roosevelt created Mesa Verde National Park, which includes more than 600 cliff dwellings in southwest Colorado, just three weeks after he signed the Antiquities Act. In 1907 he proclaimed Chaco Canyon National Monument, in northwest New Mexico. Woodrow Wilson designated Bandelier National Monument north of Santa Fe, N.M nine years later.

Cultural areas that Hewett ranked as of lower importance also quickly gained protection. In 1906 Roosevelt designated the 60,000-acre Petrified Forest National Monument near Holbrook, Ariz., Montezuma Castle National Monument near Camp Verde, Ariz. and El Moro National Monument near Ramah, N.M. He added the Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument near Silver City, N.M in 1907.

Despite several efforts over the past 80 years, more than a century would pass before the vast number of priceless antiquities remaining within Hewett’s Bluff district would be designated Bears Ears National Monument.

“With more than 100,000 archeological sites, there is just no place that is more deserving of protection, particularly given its importance in the passage of the Antiquities Act,” says Josh Ewing, executive director of Friends of Cedar Mesa, a Bluff environmental group working to protect Bears Ears.

Obama’s Bears Ears proclamation came after numerous public meetings over the course of five years held by proponents and opponents of the monument. The public meetings culminated with a contentious field hearing held by former Interior Secretary Sally Jewell in Bluff in July 2016.

Obama’s proclamation begins with the following passage:

“Rising from the center of the southeastern Utah landscape and visible from every direction are twin buttes so distinctive that in each of the native languages of the region their name is the same: Hoon’Naqvut, Shash Jáa, Kwiyagatu Nukavachi, Ansh An Lashokdiwe, or ‘Bears Ears.’

“For hundreds of generations, native peoples lived in the surrounding deep sandstone canyons, desert mesas, and meadow mountaintops, which constitute one of the densest and most significant cultural landscapes in the United States.

“Abundant rock art, ancient cliff dwellings, ceremonial sites, and countless other artifacts provide an extraordinary archaeological and cultural record that is important to us all, but most notably the land is profoundly sacred to many Native American tribes, including the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, Navajo Nation, Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah Ouray, Hopi Nation, and Zuni Tribe.”

Setting Aside a Bitter Past

The willingness of these five tribes to set aside longstanding disputes over land, cultural differences and development priorities and instead work together by forming the Bears Ears Inter-tribal Coalition in July 2015 ultimately led to the creation of the monument.

“The coalition was formed to be able to address the federal government on federal public lands at a government-to-government level,” says Carleton Bowkatey, a Zuni tribal councilmember and co-chairman of the Bears Ears Commission. “We believe that was the missing component in the grassroots efforts.”

The coalition used years of research and documentation collected by the Salt Lake City-based nonprofit Utah Diné Bikéyah to prepare the formal Bears Ears National Monument proposal. The proposal, which requested 1.9 million acres be included in the new monument, was presented to Obama in October 2015.

Bowkatey says the Bears Ears collaborative management plan “will promote tribal interests” and serves as a model that can help resolve conflicts over land use that “will prevent other situations such as the Dakota Access Pipeline protests from occurring.”

He adds, “When you look at the language of the proclamation it specifically states that traditional cultural knowledge is a scientific object worthy of value. Now that we are the ones determining the value, we are not letting that go.”

Utah Leaders Oppose Bears Ears

Filfred says repeated efforts during the tribal coalition’s development of the monument proposal to meet with state and local officials went nowhere as tribal overtures to hold discussions were met with silence.

“The whole Utah delegation is against us and they have been for many years,” he says.

That has continued. The Utah Congressional delegation, state legislature, governor and the San Juan County commission where Bears Ears is located all came out against the monument and lobbied President Trump to rescind Obama’s proclamation.

In response Trump issued an April 26 executive order requiring Zinke to review any 100,000-acre or larger national monument created in the past 21 years. The Bears Ears review was to be completed within 45 days, with the rest of the reviews due in 120 days.

Trump’s executive order expands the criteria that should be used to designate national monuments beyond the Act’s original language by including “public outreach and proper coordination with State, tribal and local officials” and the need to take into consideration “achieving energy independence” and restrictions on public access that could curtail “economic growth.”

“Designations should be made,” the order states, “in accordance with the requirements and original objectives of the Act and appropriately balance the protection of landmarks, structures, and objects against the appropriate use of Federal lands and the effects on surrounding lands and communities.”

Trump’s order adds a balancing requirement to the Antiquities Act, which is not part of the law, to provide justification for rescinding or curtailing the size of national monuments. But legal scholars say he doesn’t have the power to change previously established monuments.

“The President lacks the legal authority to abolish or diminish national monuments,” concludes a Virginia Law Review article published Monday written by four prominent environmental and land-use professors, including Squillace. “Instead, these powers are reserved to Congress,” the authors write.

Moving Forward

Shaun Chapoose, the Unitah and Ouray Ute representative on the Bears Ears Commission, says the commission is going to continue working with the federal land agencies to develop a collaborative management plan for Bears Ears until something tangible changes.

“We need to manage exactly how the proclamation is stated until that is either reaffirmed or changed,” Chapoose says. “So as far as I’m concerned, the monument is designated.”

History has already been made, he adds.

“It has to be emphasized that this is the first time that actual sovereign tribes, elected tribal leaders, engaged in a process that they had never done before and through their effort they were able to get the monument designated,” Chapoose says.

Chapoose is taking a wait-and-see attitude over the political and legal firestorms surrounding Bears Ears.

“I think the legal standing that protects Bears Ears is untested,” Chapoose says. “A lot of the rhetoric you hear is that it has never been challenged but it could be challenged. Well, I guess we’re going to find out.”

Previously on The Revelator:

Does Trump Really Have the Authority to Shrink National Monuments?

Pardon me for speaking frankly. The principal problem with Bears Ears is that white Nordic-descended people who live in Utah, and who do not practice Native American religions, do not have any respect for other-people’s-religion or cultural heritage.

I am old and retired, and as a result I can remember back into the 1950’s and 1960’s when on weekends young and middle-aged Utah residents, each with a large pack of kids, would “go out into the countryside”, roam around and look for old baskets and pots which they could sell to wholesalers called “traders”. The traders in turn would evaluate what the families had collected and split them between museum quality, collector quality and tourist quality artifacts. The traders would make money and the families would make money and everyone was happy.

Now in the 2000’s people in Utah who remember profiting from collecting on Federal lands are highly resentful of all of the Federal regulations which have essentially criminalized and mostly shut down what they considered a wholesome and profitable family activity. When there are no Native American ears around to hear, the rhetoric it is very intense.

The descendants of the collectors and traders believe that their “rights” have been taken away as Federal regulation of Federal land has increased. You won’t find those rights in a court case book or in a Federal statute, but the descendants believe they known their rights even if those rights never existed.

And of course the people who resent the taking away of their rightful wholesome profit making activities on Federal land vote Republican.

Given the absolutely venal actions coming out of the White House, Cabinet offices and House/Senate Leadership, people who want to preserve what is on Federal land in the West should brace for atrocious conduct from the Republicans, far more atrocious than anything gentlepeople would expect.

Republicans in Utah and Washington, and all across America, are out to prove that Nixon and all the policy-making President’s Men were ineffectual wimps.

It is sadly ironic and heartbreakingly tragic that lands once home only to Native American tribes have to ask a foreign federal government to protect land that should be theirs.

I say return Bears Ears to the stewardship of a coalition of Native American tribes who can then oversee the land’s management.

Additionally, because of the former federal policy of the ethnic cleansing of Native American tribes, American taxpayers should pay for its management.

For those who diminish the crimes of genocide against Native Americans or who think the genocides’ legacies are too far in the past, please be aware that recognition of the ethnic cleansing was admitted by the head of the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs on Sept. 8, 2000.

The legacies of the multiple genocidal pogroms against Native Americans still have repercussions today. Moreover, these genocidal campaigns have never been completely redressed.

Financial redress would go a long way in alleviating some of the challenges faced by Native American communities. Such redress should also include the deeding of federal land back to Native American tribes.

It is unfortunate that the United States did not ratify membership in the International Criminal Court; otherwise, a case in that court could be brought against the federal government for its genocide of many Native American tribes. In a just world, the adjudication would surely include what I previously mentioned: financial redress and deeding federal land back to the rightful owners.

(By the way: an excellent and well-written article.)

Well done. Well researched and written piece, thank you John and CBD.

The article’s title point cannot be made too often. The Bears Ears is why the Antiquities Act was created. 110 years is hardly a “midnight monument.”