By Elizabeth Wandrag, University of Canberra and Haldre Rogers, Iowa State University

Can a snake bring down a forest? If we’re talking about the Pacific island of Guam, the answer may well be yes.

Our research adds to mounting evidence that the killing of many of the island’s bird species by an invasive species of snake is having severe knock-on effects for Guam’s trees, which rely on the birds to spread their seeds.

Invasive predators are known to wreak havoc on native animal populations, but our study shows how the knock-on effects can be bad news for native forests too.

Globally, invasive predators have been implicated in the extinction of 142 bird, mammal and reptile species, with a further 596 species classed as vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered. But the indirect effects of these extinctions on entire ecosystems such as forests are much harder to study.

The brown tree snake was accidentally introduced to Guam in the mid-1940s and rapidly spread across the island. At the same time, bird populations on Guam mysteriously began to decline. For years, no one knew why.

In 1987 the US ecologist Julie Savidge provided conclusive evidence that the two were linked: the brown tree snake was eating the island’s birds. Today, 10 of Guam’s 12 original forest bird species have been lost. The remaining two are considered functionally extinct.

But the ecological damage doesn’t stop there. The loss of native bird species has triggered some unexpected changes in Guam’s forests. Both the establishment of new trees and the diversity of those trees is falling. These changes show how an invasive predator can indirectly yet significantly alter an entire ecosystem.

Birds and trees

Birds are very important to trees. In the tropics, up to 90 percent of tree species rely on animals, often birds, to spread their seeds. Birds eat fruit from the trees and then defecate the undigested seeds far away from the parent tree’s canopy, where there are fewer predators and pathogens that specialise on that species, where competition for light, water and nutrients is less intense, and where seeds can take advantage of promising new real estate when old trees die.

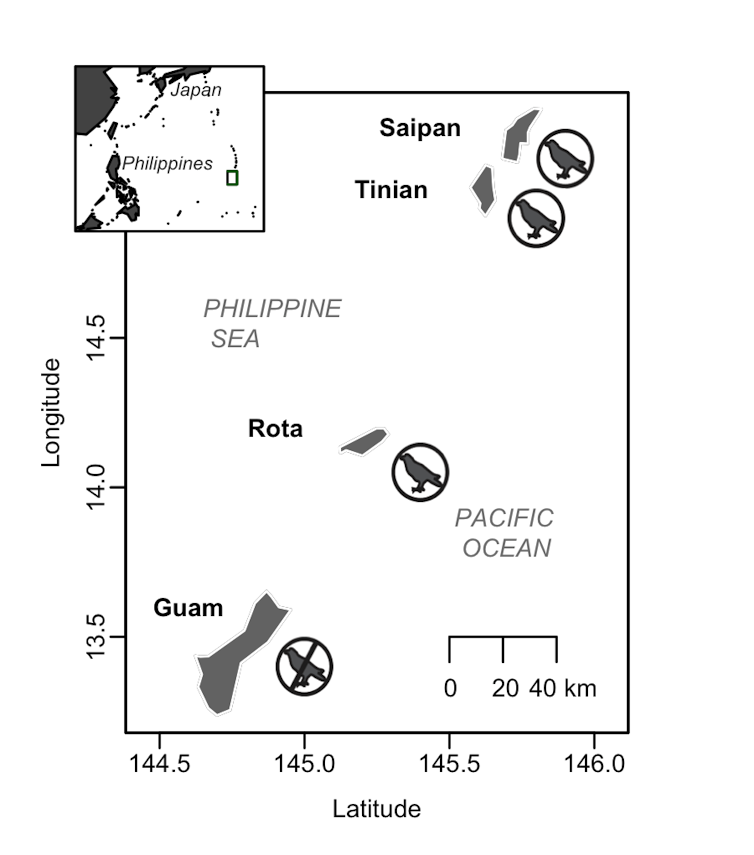

Without birds, roughly 95 percent of seeds of two common tree species on Guam (Psychotria mariana and Premna serratifolia) land directly beneath their parent tree. Compare that with the nearby islands of Saipan, Tinian and Rota – none of which have brown tree snakes – where less than 40 percent of seeds land near their parent tree. On Saipan, seeds that escape their parent tree are five times more likely to survive.

What’s more, passing through the gut of an animal can actually increase the likelihood that a seed will germinate. On Guam, seeds that had been eaten by birds were two to four times more likely to germinate than those that hadn’t.

Overall, for the roughly 70 percent of tree species on Guam that rely on birds to spread their seeds, research suggests that the bird deaths caused by the brown tree snake have reduced the establishment of new tree seedlings by 61-92 percent, depending on the species.

Forests’ future threatened

These numbers suggest that many tree species in Guam are under serious threat, which in turn threatens the species diversity of the island’s forests.

Our new research, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, examined the number of seedling species growing in treefall gaps on Guam compared with Saipan and Rota, which still have their birds.

Treefall gaps appear when an adult tree dies, opening up the canopy and increasing the light that reaches the forest floor. Many species rely on this increased light for germination and early growth, so these gaps are hotspots for new seedlings.

We found that Saipan and Rota had roughly double the number of species of seedlings growing in these gaps, compared with Guam. What’s more, seedling species on Guam tended to be clumped together, as you might expect if more than 90% of seeds are falling beneath their parent trees.

We also found that birds are important in moving the seeds of certain types of species to gaps. In forests, “pioneer species” are those that rapidly colonise gaps, exploiting the increased light to grow fast and reproduce young. Crucially, we found pioneer species in all gaps on islands with birds, but in very few gaps on Guam, where these species could be at risk of being lost entirely.

Invasive predators are a reality for many ecosystems, particularly on islands, and the situation on Guam is particularly extreme. Perhaps nowhere else in the world has experienced such dramatic losses of native fauna as a result of invasion.

While these direct impacts of invasion are astounding, the indirect impacts cascading through the ecosystem are just starting to unfold, and may prove to be similarly catastrophic.

Elizabeth Wandrag, Postdoctoral Fellow, Ecology, University of Canberra and Haldre Rogers, Assistant Professor, Iowa State University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

1 thought on “Guam’s Forests Are Being Killed – By A Snake”

Comments are closed.