Nearly 1.5 billion people around the world, including 689 million children, live in such extreme poverty that it affects their health — and often the environment around them — according to a powerful new study issued this month by the Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative.

“We’re looking at very, very acute and basic forms of poverty,” says Sabina Alkire, director of the initiative, who has spent more than 20 years studying the issue.

Poverty rates have actually gotten slightly better overall in the past few years, Alkire reports, but little has changed when it comes to the worst-affected populations around the world. “The fact that it remains so prevalent is quite worrying,” she says. “We compute these things and then we cry when we see what’s on our screens.”

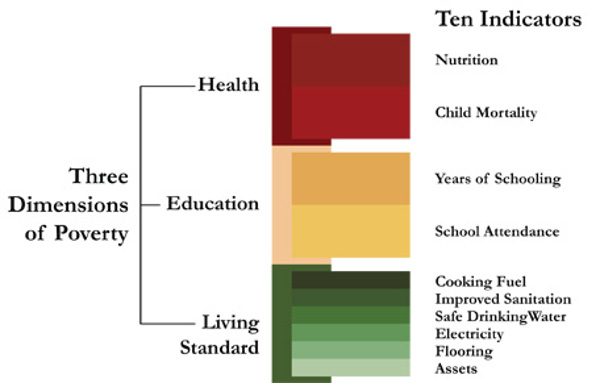

The initiative calls this “multidimensional poverty,” a measure that reflects not just lack of income but how this impacts — or is impacted by — health, education and living standards. Oxford’s Multidimensional Poverty Index looks at populations for the presence of ten weighted factors (below) reveal which populations around the world are most at risk.

Alkire points out that several of the factors driving multidimensional poverty stem from situations in which people live in environmentally unsafe conditions. These factors include malnutrition, lack of access to sanitation and safe drinking water, and the use of polluting solid cooking fuels such as charcoal, wood or dung.

Alkire points out that several of the factors driving multidimensional poverty stem from situations in which people live in environmentally unsafe conditions. These factors include malnutrition, lack of access to sanitation and safe drinking water, and the use of polluting solid cooking fuels such as charcoal, wood or dung.

Alkire says there are also “very clear links” between changing environmental conditions and extreme poverty. For example the report found that between 98 and 99 percent of the people in Chad’s Lac and Wadi Fira regions live in extreme poverty. “That is clearly affected by the drought in Chad,” Alkire says. “You can see the drought-affected regions. Poverty has increased and those areas have now unfortunately overtaken others as the poorest regions of the world.”

Other areas have experienced dramatically different environmental conditions. “We could talk about the borders of Myanmar and Bangladesh and the floods there and the interaction with poverty,” Alkire says. One of the factors in the multidimensional poverty index, she points out, is living in homes without floors. “We can see when floods wipe out peoples’ homes by the increase in houses without floors in the index,” she says.

Multidimensional poverty, meanwhile, has its own broader environmental impacts, including an over-reliance on hunting wild game for sustenance, as well as deforestation, air pollution and improper waste disposal.

Alkire adds that there are enormous opportunities to improve our understanding of the environmental impacts of and on poverty. “There’s a big need for joint analysis,” she says. “I’m hoping to attract environmentalists, whether they’re working on deforestation, air pollution, climate or other areas,” who might be able to combine environmental data with Oxford’s regional population data. “We have a paper coming out next month on how to include environmental and natural sources in the Multidimensional Poverty Index,” she says. “We’ve been able to do it conceptually, but it’s so difficult to get data on climactic or environmental natural depravations that affect entire populations.”

A Critical Need for Funding

The Oxford report comes at a time when President Trump has proposed drastic cuts to U.S. international financial assistance, including for health and food programs. The Trump administration also cut off funding to the United Nations Population Fund, which aids reproductive health services in poorer countries around the world. A recent report from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that these cuts could result in tens of thousands of illnesses and deaths around the world and that at least 6.5 million women would lose access to contraceptives.

Alkire calls this financial aid “fundamental” for reducing worldwide child poverty. “These cuts are really devastating,” she says with a sigh.

In part, she adds, that’s because these aid programs themselves are already severely underfunded. “People don’t understand just how little we give in international aid,” she says. “When you do surveys, the American people systematically overstate what they think we give and how generous we are.” She points to Chad again as an example. “Chad is a very poor country, but if you look at how many dollars Chad receives from all bilateral governments, the World Bank, UNICEF and other sources, it’s just $5.89 per person, per year. That is not very much.”

India is another example. “There are over half a billion poor people in India, by our count,” Alkire says. “As a global community, we give less than $2 per person per year.”

The total amount given to help alleviate poverty worldwide, Alkire says, “is ridiculously small. We assume that we are very generous, but from a poor person’s perspective we are not.”

On top of that, Alkire says, what little funding is actually granted often goes to the wrong places, with aid being based on political priorities, such as national security, rather than humanitarian ones. “Chad is not a security country, but it’s terribly important in human terms,” she says.

The Oxford data could help reprioritize that distribution, Alkire says. “We really do have a bit of a magnifying glass on poverty. We have data for 103 countries, many over multiple time periods. We’re hoping that others will both use the data and be troubled by the data.”

Even if the world governments don’t take action based on Oxford’s findings, Alkire suggests, the report can still help others in taking action to help alleviate some of this poverty: “Who knows where the states will go in terms of these conversations — but individuals can still act in ways they know will be appreciated.”

Previously in The Revelator:

Trump Budget Would Leave Low-Income Families Feeling the Heat

Elephant Ambassador in Chad: A Conversation with Stephanie Vergniault

The United States continues to hemorrhage its treasure, not to mention the loss of troops, in its pursuit of imperial delusions of grandeur at the expense of providing more foreign aid in an era where that aid appears to be targeted for signicant reduction.

It’s a cynical Faustian quest that sacrifices humanitarian aid and oxymoronically promotes peace and democracy through the barrel of a gun and the selling of state-of-the-art arms to oppressive states, which fund the carnage evident in the Middle East and Africa, especially North Africa, today.

Only the self-deceived, the greedy (military-industrial complex and its stock owners and congressional overseers) and the jingoistic actually believe war brings peace and humanitarian aid has no value or benefit to the United States.